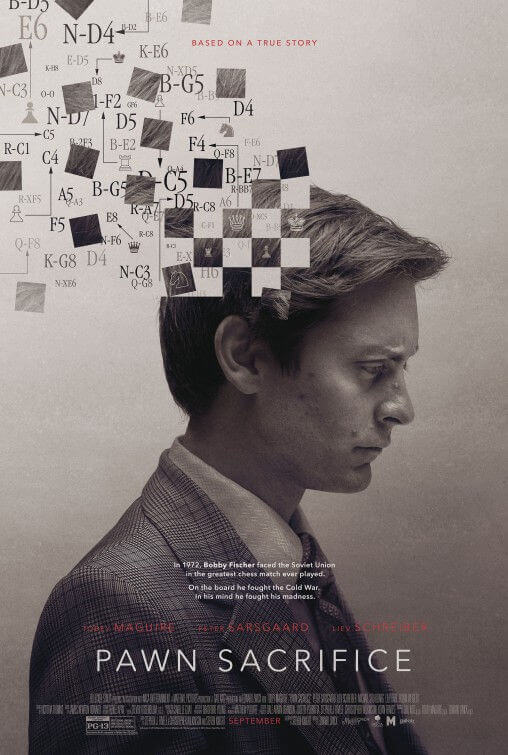

Pawn Sacrifice

By Brian Eggert |

Just because it goes through the usual motions of a historical biopic doesn’t mean Pawn Sacrifice isn’t a fascinating, well-acted, if traditionally presented story. Screenwriter Steven Knight, who most recently wrote and directed Locke (2013), compiles the life of Brooklyn native Bobby Fischer, better known as the greatest chess player who ever lived. Behind the camera is director Edward Zwick, who built his career on sweeping historical dramas, usually in the action realm, from Glory (1989) to Defiance (2008). More recently, Zwick parted with his big-budget productions for independently financed, lower-budget efforts such as Love & Other Drugs (2010) and now this. Zwick’s professional job assembling Fischer’s life, Knight’s solid writing, and Tobey Maguire’s paranoid, method-style performance make the predictable structure worth the experience.

Bobby Fischer’s life of genius and madness has already been covered in Liz Garbus’ 2011 documentary Bobby Fischer Against the World and, at least in terms of his strategy and obsession, in Steve Zaillian’s 1993 drama Searching for Bobby Fischer. But Zwick’s film represents the first biographical attempt to understand Fischer, a world celebrity by the age of 13, and a progressively more enigmatic and radical figure in the years before his death in 2008. Formed around the famous World Championship match in Reykjavik, Iceland, that had the entire world watching, the film reels back to the 1950s and tells both of Fischer’s life and how his victories at world competitions represented a Cold War victory for the United States against the Soviets, who dominated the chess world.

Young Bobby, played at various stages by Aiden Lovekamp and Seamus Davey-Fitzpatrick, lives with his inattentive single mother (Robin Weigert) and sister (Lily Rabe). Hypersensitive to every sensory detail around him, Bobby learns to focus on the chessboard. His natural talent and competitiveness perverse into brilliance and arrogance under his first teacher Carmine (Conrad Pla). By the time he’s reached adulthood, now played by Maguire, he’s convinced he’s the best chess player in the world and that he just needs to claim the trophy to prove it. After walking out of the 1962 Chess Olympiad in Varna, Bulgaria, where he accuses the Russians of strategizing against him, he retires briefly from chess. He’s convinced to return by patriotic lawyer Paul Marshall (Michael Stuhlbarg), who understands that to defeat the Russians at their game would be a major victory for America. Once Bobby agrees, William Lombardy (Peter Sarsgaard), the Catholic priest and chess grandmaster who coached a younger Bobby, joins their crusade, which is secretly funded by the U.S. government.

Meanwhile, Bobby suspects both sides are watching him, and his occasionally debilitating paranoia, combined with his outrageous egotism, turn him into a tragic and driven monster who tears apart hotel rooms in search of recording devices. Marshall and Lombardy endure his outbursts and refuse to get him help, knowing treatment for Bobby’s mental issues could taper his playing and that his victory could save a nation (hence the metaphoric title). Indeed, Bobby’s nemesis is the Russian champion Boris Spassky (Liev Schreiber), who stays in posh hotels and travels with a flashy entourage, while Bobby remains “the boy from Brooklyn”. Their mutual rivalry plays like something out of Rocky IV (1985) at times (complete with a fabricated scene on a beach where Bobby shouts, “I’m coming for you! Do you hear me?! I’m coming for you!”). Still, Maguire’s furious, method performance deserves recognition for capturing the subject’s layers of methodical talent and schizophrenia.

Audiences aren’t expected to know the rules of chess to understand the tension of certain scenes. Zwick’s editor Steven Rosenblum cuts to shots of pieces on the board making moves that remain indiscernible due to the extreme close-up. Later scenes, specifically those where Bobby competes against Spassky, show the entire board and concentrate on the moves, the significance of which is much more profound for those familiar with the game. Though most of us know the outcome of Fischer and Spassky’s eventual face-off, the film helps us understand the character through Maguire’s impassioned portrayal. Although we must admire Bobby Fischer’s genius, his declining mental state and increasing anti-Semitism, despite being a Jew himself, transforms him into something of a human oddity—a subject to be studied rather than truly understood. After all, how does one understand madness? Or genius, for that matter? Pawn Sacrifice paints a portrait that shows us how, when true genius of this kind is discovered, it must be supported to its fullest potential, leaving everyone else to follow in awe of its rare whirlwind.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review