Past Lives

By Brian Eggert |

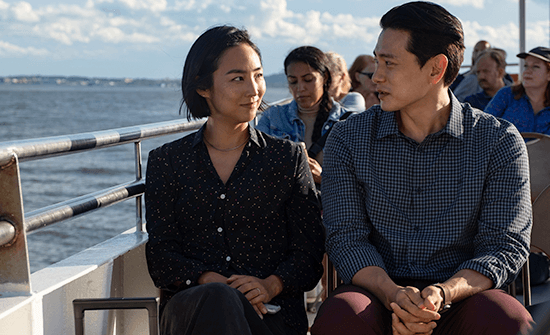

Past Lives opens with a curious prompt. In a New York night spot, two unseen patrons play the “Who are they?” people-watching game about three thirtysomethings on the opposite side of the bar—a woman seated between two men—and speculate about their lives. The woman faces the man to her right, deep in conversation. Her back is to the man on her left, who seems excluded from the exchange, apart from the occasional looks of affection the woman gives him. The people playing the game wonder whether the three of them are coworkers or perhaps caught in a love triangle, with one of them a third wheel or paramour. Reading their body language, they don’t make sense. The speculation ends with uncertainty; whatever their situation is, it goes beyond appearances. All at once, the woman across the bar looks at the two playing the game, locking eyes with the subjective camera and almost breaking the fourth wall. The shot seems to ask, “Who is this person?” The answer is complicated, both textually and extratextually. From this prologue, an aching melodrama unfolds that goes beyond the nature of a relationship between three people. Past Lives investigates the choices and layers that compose a person’s identity.

The film marks the directorial debut of playwright Celine Song, who delivers an aching and thoughtfully considered film. Every choice—from the dialogue to the actors’ subtle gestures to the camerawork—feels in narrative and stylistic alignment. An overwhelmingly assured debut, it’s also a work of autofiction that functions as a text and metatext. Past Lives was inspired by events in Song’s life. Like her protagonist, Nora (played as an adult by Greta Lee), Song immigrated from South Korea to Canada in her adolescence, received an MFA from Columbia, and worked in the New York theater scene. And like the film’s opening, Song once sat at a bar between two men. One was her American husband; the other was her first love from childhood, who was visiting her from Korea. Along with Nora preparing a play-within-the-movie with lines from Song’s actual play, Endings (2020), another self-referential text, Past Lives is a beautiful and nuanced personal expression by Song that considers how the past is written on our lives, no matter how hard we try to erase it.

After the prologue, the film opens with 12-year-old Nora (Moon Seung-ah) in Korea, set to immigrate to Canada with her family in a few days. Hoping to instill fond childhood memories of their home country, Nora’s mother (Ji Hye Yoon) encourages her to make a date with her best friend, Hae Sung (Leem Seung-min). After what amounts to a playdate in a sculpture park, Nora and Hae Sung say an unceremonious goodbye, leaving Hae Sung wounded. They will not speak again for 12 years when Nora, now studying in New York, learns that Hae Sung (Teo Yoo), who is going through his mandatory military service in Korea, has been looking for her on Facebook. The two reconnect via Skype, sharing memories about their adolescent friendship. In many ways, both remain the same people. Hae Sung is reserved and polite, always listening yet afraid to express himself. Nora, who often cried as a characteristic Korean child and found comfort in Hae Sung, now reserves her emotions to conform to her hardened New York surroundings. When they finally say, “I miss you,” it feels like a breakthrough.

But Nora’s relentless ambition to become a writer, which earned Hae Sung’s nickname for her (“psycho”), derails their potential coupling. Even at age 12, just before Nora’s family leaves for Canada, she tells a fellow student, “Koreans don’t win the Nobel Prize for Literature.” At 24, she’s no less ambitious, having changed her ideal award to a Pulitzer. So a serious or even long-distance relationship with Hae Sung is impossible; she has another year of school, and her desire to become a writer takes precedence. In that sense, Past Lives offers a minor commentary on the ambitiousness of creatives who place their chosen form of expression above all else, closing off their past to facilitate their future. For Nora, that means shutting down her Korean side, breaking off communication with Hae Sung, and then pursuing an artist’s residency in Montauk instead. There, she meets Arthur (John Magaro), who will become her husband. This is where Song’s origins as a trained playwright become apparent in the script, and her efforts as a first-time director become so impressive. The moments between Nora and Hae Sung are loaded with unspoken bonds and muted longing, reliant on decidedly cinematic and restrained body language, like scenes in In the Mood for Love (2000). But Nora and Arthur have a relationship rooted in open conversation like characters from a play.

But Nora’s relentless ambition to become a writer, which earned Hae Sung’s nickname for her (“psycho”), derails their potential coupling. Even at age 12, just before Nora’s family leaves for Canada, she tells a fellow student, “Koreans don’t win the Nobel Prize for Literature.” At 24, she’s no less ambitious, having changed her ideal award to a Pulitzer. So a serious or even long-distance relationship with Hae Sung is impossible; she has another year of school, and her desire to become a writer takes precedence. In that sense, Past Lives offers a minor commentary on the ambitiousness of creatives who place their chosen form of expression above all else, closing off their past to facilitate their future. For Nora, that means shutting down her Korean side, breaking off communication with Hae Sung, and then pursuing an artist’s residency in Montauk instead. There, she meets Arthur (John Magaro), who will become her husband. This is where Song’s origins as a trained playwright become apparent in the script, and her efforts as a first-time director become so impressive. The moments between Nora and Hae Sung are loaded with unspoken bonds and muted longing, reliant on decidedly cinematic and restrained body language, like scenes in In the Mood for Love (2000). But Nora and Arthur have a relationship rooted in open conversation like characters from a play.

Song’s screenplay contains traces of theatrical dramaturgy, where characters more openly express their feelings through dialogue. Another 12 years later, Nora and Arthur are married and living in the East Village, and Hae Sung plans to visit his first love. Their past is not a secret from Arthur, who has been told every detail about Nora and Hae Sung’s relationship, and he responds to the situation with guarded understanding. One of the film’s best scenes involves Nora and Arthur in bed, talking over “what if” scenarios between Nora and Hae Sung. What if she had never left Korea, and what if she had met some other guy at the Montauk residency? Would she be happier with Hae Sung? Echoing Song’s self-awareness and interest in literary motifs, Arthur notes how, in a typical story, he would be an evil white husband keeping the two destined-since-childhood Korean lovers apart. Such dialogue can seem pointed; then again, two trained writers are bound to see how their relationship would be reflected in art, and by extension, underline how Song has broken from conventions. Moreover, Song introduces a discussion of “In-Yun,” a Korean concept that says married people have 8,000 layers of In-Yun—a measure of providence or destiny. But that doesn’t mean Nora and Hae Sung, or even Arthur and Hae Sung, can’t share many layers of In-Yun too.

However stagelike and candidly metaphorical the dialogue may seem at times, Song’s visual treatment is minimalist but no less symbolic, and therein cinematic, resulting in a film that contains the aesthetic regimentation of a seasoned master. Working with cinematographer Shabier Kirchner (who shot Steve McQueen’s Small Axe anthology of films), Song portrays early scenes in Korea as muted and drained of color, thus life. When Nora moves to America, the imagery is filled with vibrant city streets, luminous sunsets, and lush green spaces in Montauk. Along with the opening’s “Who is this person?” prompt, Past Lives finds an unlikely parallel in David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia (1962)—an epic investigation of its eponymous character that begins by asking him “Who are you?” and spends the remainder of the film searching for that answer. But where Lean’s camera follows the Western mode of progression from left to right to denote progress, note how Song’s camera often moves from right to left, as though moving backward in time. This camera movement suggests how Nora is drawn to her past and how dwelling on the past represents a step in the wrong direction.

Once she says goodbye to Hae Sung, perhaps for the last time, the camera follows her forward, from left to right, denoting her progression for accepting the past as part of her identity and no longer needing to deny or dwell on it. Doing so requires Nora to access a part of herself she has buried—the Korean part that she dismissed for so long to pursue her creative ambitions. In the film’s final, heartbreaking moment, Nora also allows herself to experience something she hasn’t done since childhood and becomes whole for it. Particularly in the last, devastating scene, Lee’s performance is a tour de force of emotional composure that breaks down to staggering effect. Besides being a probing dramatist, Song is also incredible with her actors, directing them to enhance every line, Magaro above all. Whereas Nora and Hae Sung’s characters often feel defined by what remains unsaid, Magaro has the most wounded dialogue to perform, offering aching scenes such as the moment in bed where he admits to feeling distanced from his wife, who sleep-talks and dreams in Korean, a language he barely speaks.

Once she says goodbye to Hae Sung, perhaps for the last time, the camera follows her forward, from left to right, denoting her progression for accepting the past as part of her identity and no longer needing to deny or dwell on it. Doing so requires Nora to access a part of herself she has buried—the Korean part that she dismissed for so long to pursue her creative ambitions. In the film’s final, heartbreaking moment, Nora also allows herself to experience something she hasn’t done since childhood and becomes whole for it. Particularly in the last, devastating scene, Lee’s performance is a tour de force of emotional composure that breaks down to staggering effect. Besides being a probing dramatist, Song is also incredible with her actors, directing them to enhance every line, Magaro above all. Whereas Nora and Hae Sung’s characters often feel defined by what remains unsaid, Magaro has the most wounded dialogue to perform, offering aching scenes such as the moment in bed where he admits to feeling distanced from his wife, who sleep-talks and dreams in Korean, a language he barely speaks.

Although Nora might feel at a remove, Past Lives is a mature story about a woman’s inner life, framed by her relationship with two vulnerable men, her past, and her subjectivity within a shifting cultural backdrop. It’s feminist for making Nora’s transnational identity, thus Song’s, its primary question. In its love triangle, the structure might earn comparisons to Casablanca (1942), concerning the bonds of Nora’s past and memories, which have been romanticized over time, and which go unrealized for their impracticalities in the future. After all, whatever their connection as children, Nora and Hae Sung would never work. He’s “so Korean,” as Nora observes in a comic scene. But more than that, Nora has changed from a Korean to a Canadian to a New Yorker. And her relationship with Arthur works so well, partly because it aligns with and supports her work as a playwright. Even as Nora describes their marriage to Hae Sung like “planting two trees in one pot,” the alternative with Hae Sung would be untenable. As a fiercely driven creative, she knows, “I’m not gonna miss my rehearsal for some dude.” In her self-awareness, Nora’s choices may challenge an audience’s willingness to like her, even though they will allow us to understand her.

Past Lives, then, is less a broken-hearted romance than a tragic search for identity. One of the year’s best films, it’s about how life sometimes requires that people and places get left behind, even though they leave traces that remain a part of us. Powerful and intentional in every detail, no matter how minor, the film mourns those contained worlds and alternate timelines that could have been, yet it also embraces how life is a series of choices that lead to the here and now. It’s an idea referenced when, in one scene, Nora recommends that Hae Sung watch Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004), a film about erasing past lovers from your memory. To be sure, Past Lives has much to say as a text, but there’s plenty to uncover as an intertext as well. With its rich and multifaceted construction, the film continues to unfold in the hours and days after screening it, not unlike Nora’s identity through the course of this filmic investigation. No matter how much Nora attempts to deny or compartmentalize the importance of Hae Sung and Korea in her new life with Arthur in New York, Nora is the summa of her experiences. You can’t go back, but that doesn’t mean you can’t cherish or even mourn your past and what you may have lost along the way.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review