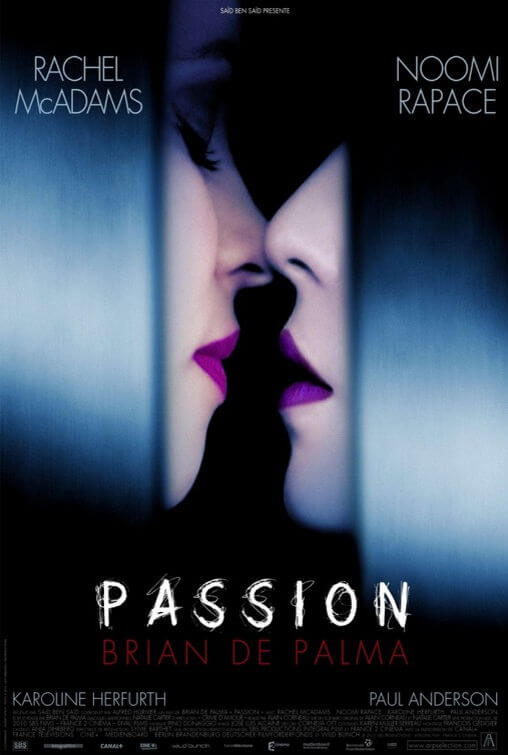

Passion

By Brian Eggert |

For Passion, one should avoid the critical norm of comparing director Brian De Palma’s works to that of other filmmakers. Instead, better comparisons can be made to his own work and not to, say, the late Alain Corneau, French director of Crime d’amour (2010), on which Passion is based. Nor even De Palma’s cinematic soulmate Alfred Hitchcock. Although De Palma’s thrillers have often borrowed from the Master of Suspense, sometimes with varying measures of homage (and not infrequent accusations of directorial piracy), his latest feels oddly self-referential. Working from his own scripted adaptation, this supreme visualist keeps the same basic events of Corneau’s picture intact but changes a few details in the plot and story structure, decorating the material with touches from his earlier films such as Femme Fatale (2002), Raising Cain (1992), and Sisters (1973). Featuring two compelling performances by his female leads, Noomi Rapace and Rachel McAdams, only the film’s scenario wavers in its third act twists that range from far-fetched to unsatisfying in ways familiar to De Palma enthusiasts. To explore these elements in detail, key points of the plot will be discussed throughout this review.

Professional and romantic competition erupts at a Berlin ad agency when a seasoned pro, the purring and modish Christine (McAdams), steals credit for a sharp campaign idea conceived by her devoted apprentice, the mousy Isabella (Rapace). “There’s no backstabbing here. This is business,” Christine explains. Isabelle responds by bedding Christine’s boyfriend Dirk (Paul Anderson), although there’s plenty of bisexual tension between this kinky executive and her eager-to-please underling that De Palma is quick to exploit. As the head games and corporate cat-and-mouse ensues, Isabelle endures Christine’s weepy confession about the loss of her twin sister as a child, and the two grow false ties, which are cut with further backstabbing. Meanwhile, Isabelle’s assistant Dani (Karoline Herfurth) fawns over her and warns that Christine is dangerous. Indeed, the scheming Christine sends a “revenge is a dish best served cold” email from Isabelle’s computer just before she stages Isabelle’s humiliation in front of the entire office. Nevertheless, as things escalate, it’s Christine who ends up dead, her throat slashed by a masked killer.

This well-motivated setup of intriguing female businesswomen collapses into a silly, underdeveloped last half-hour when Isabelle finds herself zonked on sleeping pills and facing accusations after Christine’s murder. The police claim Isabelle’s motive lies in the false email sent by Christine, but fail to notice it was sent before Isabelle’s public humiliation and thus before she had any real cause for revenge. Are these the dimmest detectives in Berlin? They must be. Never mind the poor procedural details; De Palma seems more interested in vague hints at Isabelle’s demented psyche. Passion turns into a Side Effects-like situation where Isabelle may or may not have hallucinated her way through a murder. Several It-Was-All-A-Dream moments occur, each laden with enough suspicious details to make us question what’s really going on: Did Isabelle hallucinate the murder? Well, no, she planned it. That much becomes clear. But what about Christine’s twin sister? Does she really exist and, even worse, is she still alive? In the final scenes, the twin returns almost from nowhere to exact revenge on Isabelle. But, of course, this is just a horrible, pill-induced nightmare. Still, we’re left to question if the twin exists, or if she’s only in Isabelle’s head as a representation of her guilt over the murder.

Too many components in Passion arrive too late, and as a result, they feel incongruous with the excellent first half. Consider the out-of-left-field addition of the twin sister. De Palma has explored murderous identical twins in both Raising Cain and Sisters, and in both films, the audience was aware early on that one twin was deranged, allowing unbearable suspense to build to a natural climax. Here the twin appears out of thin air, her presence itself suspect. If, in fact, she’s just a figment of Isabelle’s shattered mind, then there’s another problem altogether: De Palma has failed to build a monster and only just begins to tap into her pathological issues in the final two or three scenes. Isabelle’s pill-popping leads to half-baked dream sequences and shifting in and out of various realities. Besides ending the film on a low note, these lend a campy quality to the otherwise elegant treatment, not to mention a general distrust for everything onscreen, including our protagonist. Italian composer Pino Donaggio, whose scores enhanced De Palma’s earlier erotic thrillers Dressed to Kill (1980) and Body Double (1984), lends an additional corniness to the piece with his 1980s-style, sax-infused music.

Too many components in Passion arrive too late, and as a result, they feel incongruous with the excellent first half. Consider the out-of-left-field addition of the twin sister. De Palma has explored murderous identical twins in both Raising Cain and Sisters, and in both films, the audience was aware early on that one twin was deranged, allowing unbearable suspense to build to a natural climax. Here the twin appears out of thin air, her presence itself suspect. If, in fact, she’s just a figment of Isabelle’s shattered mind, then there’s another problem altogether: De Palma has failed to build a monster and only just begins to tap into her pathological issues in the final two or three scenes. Isabelle’s pill-popping leads to half-baked dream sequences and shifting in and out of various realities. Besides ending the film on a low note, these lend a campy quality to the otherwise elegant treatment, not to mention a general distrust for everything onscreen, including our protagonist. Italian composer Pino Donaggio, whose scores enhanced De Palma’s earlier erotic thrillers Dressed to Kill (1980) and Body Double (1984), lends an additional corniness to the piece with his 1980s-style, sax-infused music.

Not surprisingly, this is a gorgeously arranged and shot motion picture in the De Palma tradition, complete with the director’s regular use of split diopter lenses and his penchant for elaborately orchestrated visual sequences—the standout being when a modern ballet is cut against Christine’s murder via split-screen. Just into his seventies, this director still has absolute precision control over his craft. It’s apparent each shot is carefully planned in advance through his use of storyboards and rigorous preparation, leaving nothing to chance. Spanish cinematographer Jose Luis Alcaine makes every frame count too, lighting each scene almost to a fault—Passion looks almost artificial, with a no doubt intentional dreamlike appearance. Having been shot in Berlin in posh office buildings and other chic interiors, the film looks labored over stylistically, the frame tilted at Dutch angles and lit with dramatic shadows straight out of a classic film noir. All of this adds to our dubious feelings about Isabelle’s mental state, but unfortunately, our curiosities are never put to rest.

Also filling the frame are Rapace and McAdams, who, having reportedly improvised many of their more erotic scenes together, seem to relish playing juicy leads in a sexy thriller—the likes of which De Palma has been equally celebrated and condemned. But unlike his early career efforts that were once derided as exploitative only to have been since revisited and reassessed as the works of a master, Passion, though at times lurid, doesn’t test the grounds of trashiness. Then again, it’s difficult to imagine one of De Palma’s more scandalous titles ever reaching the market in today’s sexually conservative film industry. The sex scene has all but died out from the movies; more and more, the wholly adult subject of eroticism disappears as the entertainment industry leaves such topics to premium cable television to explore. Gone are the days when De Palma-brand erotic thrillers could reach a large audience, yet test the limits of sexuality on film and engage in a superior display of cinematic bravado. This is not to suggest that Passion could have been saved by sex. Rather, just that the state of cinema today and De Palma’s string of recent financial failures (The Black Dahlia and Redacted) have left this director to join the slew of independent filmmakers who have found their target demographic on VOD.

Like many of De Palma’s late-career disappointments, all the director’s themes are at play in Passion: obsession, voyeurism, eroticism, murder, and the warped mind of a killer—they’re all present. But they never come alive in the sensational way they do in his best films, largely because his script relies on dull twists, and yet he treats them like unpredictable revelations. De Palma gives up on his characters after Christine’s murder in favor of a guessing game as to what’s happening to Isabelle. After the first or second twist, the sad truth is we no longer care. Half-explored ideas emerge and leave the viewer scratching their head and unsatisfied, even if we’re nonetheless impressed by De Palma’s style-over-substance approach. Indeed, Femme Fatale might be Passion’s cinematic twin sister, both films being about a “protagonist” who flashes in and out of dream states in the process of self-reflection, both more interested in the visual traits of such a story over the marriage of form-follows-function. Call it “pure cinema” and admire it as such if you will, but the director has made other, similar films with tighter plotting and more involved scenarios, and most of them perform better than Passion.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review