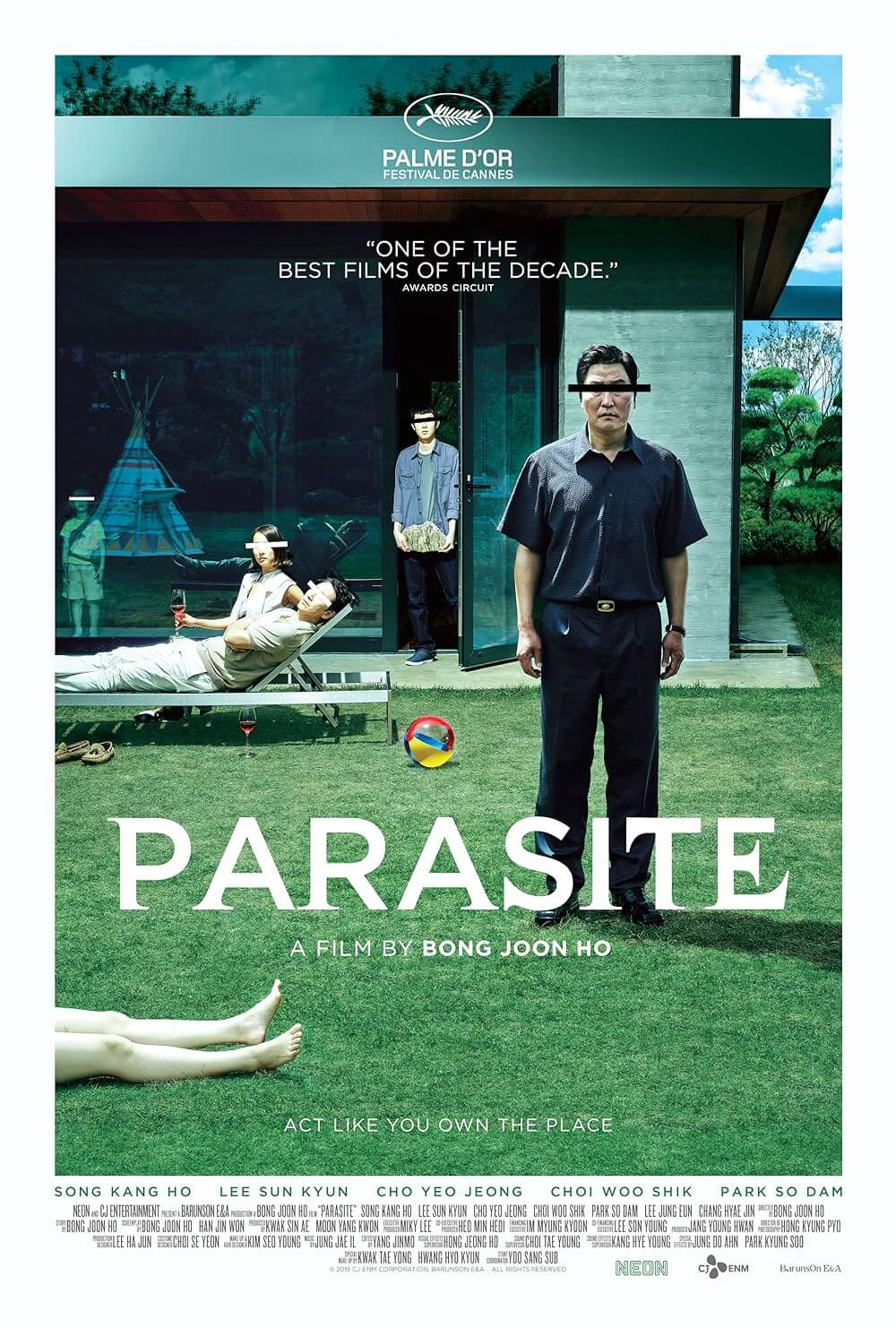

Parasite

By Brian Eggert |

From their half-basement dwelling, the Kim family looks out a narrow window onto their impoverished neighborhood in Seoul, where passers-by urinate in the street and insect foggers release noxious gases that float into homes. Inside, they dry their socks on a mobile-like hanger and fold pizza boxes for money. When they need to get a Wi-Fi signal, they hold their smartphones in the air and search their underground apartment for a signal by climbing on the toilet. It would be funny if it weren’t so sad. With the family’s conditions dire, each of them, the parents and two adult children, search for an edge, which presents itself with the Park family. An upper-middle-class couple with a teenage daughter and a young boy, the Parks live in a modernist house of cold, geometric stone and austere design, elevated in a walled space and a lush, enclosed yard that feels removed from the reality of the outside world. The juxtaposition between the underclass and the advantaged, and the events that entangle these two families in Bong Joon-ho’s brilliant Parasite, recalls a similar class and genre dynamic as the 1963 Japanese thriller High and Low. That film, directed by Akira Kurosawa, tells the story of a privileged family whose kidnapped son is held for ransom in a poor criminal’s act of class revenge. Bong’s film might be called Low and High, with its perspective situated in the sub-levels, looking up at the disparity between the rich and the less fortunate. Though, the impetus of Parasite’s class struggle materializes in a far more surprising, unconventional way.

But before this consideration of Bong’s film continues, a word of warning: After Parasite debuted at the Cannes Film Festival earlier this year, where it unanimously won the Palme d’Or, Bong asked that critics not reveal certain story elements. As much as any film, if not more, experiencing this remarkable picture without prior knowledge will enhance your impressions. Consider yourself warned that this assessment will explore the plot of Parasite with detail, less as a betrayal of Bong’s request than a celebration of his intricate, exhilarating film, whose many layers keep unfolding into the final shot. However, it should be noted, as ever, that criticism and review aggregators tend to set expectations, and the less you know about this film and its themes beforehand, the better. With little or no knowledge of what Parasite entails before seeing it, I was nonetheless drawn to the material because of its filmmaker—a master at blending genres and tones into a sophisticated cinema. Bong’s multifaceted approach is, to borrow a repeated line from a character in his latest, “so metaphorical,” reflecting the intricate and entangled nature of his characters and, to a greater extent, all human beings. So while seeing it unspoiled is ideal, seeing it again may be essential.

Though established in a specific regional setting and district, Bong and his co-writer Han Jin-won achieve a universality with Parasite, perhaps because matters of class division and economic divergence are not so much products of a distinct culture as a widespread symptom of capitalism. Bong’s films often consider the effects of capitalism on his characters, going back to The Host (2006), and that film’s critique of America’s presence in South Korea—the source of chemicals that mutate an enormous, amphibious monster, which preys on the youngest member of a working-class family. In Bong’s Snowpiercer (2014), the last remnants of humanity avoid the subzero temperatures outside by cramming into a perpetual train, where the lower classes in the rear cars rally against the elitists who occupy the front, a stirring and unforgettable metaphor. Most recently, the charming fantasy of a young girl’s intelligent superpig in Okja (2016) gave way to a horrifying discussion about the inhumane practices of factory farming and industrialized meat processing. Bong walks the fine line between overt commentary and genre filmmaking, balancing carefully on an edge that, if crossed, could mean his films become overbearing. But they never do. Their sheer entertainment value makes them accessible, but by the end, they shake their audience with their meaning. It’s a testament to the filmmaking that Parasite never feels dominated by its themes over the fates of its characters.

Though established in a specific regional setting and district, Bong and his co-writer Han Jin-won achieve a universality with Parasite, perhaps because matters of class division and economic divergence are not so much products of a distinct culture as a widespread symptom of capitalism. Bong’s films often consider the effects of capitalism on his characters, going back to The Host (2006), and that film’s critique of America’s presence in South Korea—the source of chemicals that mutate an enormous, amphibious monster, which preys on the youngest member of a working-class family. In Bong’s Snowpiercer (2014), the last remnants of humanity avoid the subzero temperatures outside by cramming into a perpetual train, where the lower classes in the rear cars rally against the elitists who occupy the front, a stirring and unforgettable metaphor. Most recently, the charming fantasy of a young girl’s intelligent superpig in Okja (2016) gave way to a horrifying discussion about the inhumane practices of factory farming and industrialized meat processing. Bong walks the fine line between overt commentary and genre filmmaking, balancing carefully on an edge that, if crossed, could mean his films become overbearing. But they never do. Their sheer entertainment value makes them accessible, but by the end, they shake their audience with their meaning. It’s a testament to the filmmaking that Parasite never feels dominated by its themes over the fates of its characters.

At the film’s center are the two families, the Kims and the Parks, but as suggested, Bong aligns the viewer with the Kims’ perspective. We understand their motivations and family dynamics, whereas the Parks have a curious, if not morbid undercurrent to their lives. The Kims’ paterfamilias, Ki-taek, played by the great South Korean actor Song Kang-ho, spends his days with his family in their cramped basement abode, barely eking out an existence yet never overwhelmed by their situation. But their fortunes change when the son, Ki-woo (Choi Woo-shik), learns of a chance to work as a well-paid English tutor for the Parks’ teenage daughter, Da-hye (Jung Zi-so). When the opportunity presents itself, Ki-woo ensures his employment by enlisting his sister to forge college documents, while Ki-taek and his wife, Chung-sook (Jang Hye-jin), look proudly on their children who have learned to survive with ingenuity and criminal cunning. Of course, Ki-woo lands the job after interviewing with the gullible Mrs. Park (Cho Yeo-jeong), who insists on calling him “Kevin” in the way some slave owners would rename their servants. Once he’s established, Ki-woo learns that the Parks’ youngest, a rambunctious boy, needs help becoming the next Basquiat. Ki-woo makes up a story about so-and-so who knows a well-respected art teacher, a role to be played by his sister, Ki-jung (Park So-dam).

Before long, Ki-woo and Ki-jung have convinced the Parks to hire their entire family, while the Parks remain unaware of their true identities. But “convinced” is the wrong word. The Kims lie, cajole, and manipulate to secure Ki-taek as the chauffeur of Mr. Park (Lee Sun-kyun) and Chung-sook as the Park family’s maid. Rather than identifying with Moon-gwang (Lee Jung-eun), the longtime housekeeper, out of lower-class solidarity, they’re happy to exploit her allergy to peaches to convince Mrs. Park that she has tuberculosis—a condition that quickly gets her fired. Setting up the former employees to sabotage them, the Kims stick to an elaborate plan, but their scheme is not to rob the Parks or to murder and replace them as doppelgängers, but to earn a lucrative income. At one point, Ki-taek observes that fifty college graduates compete for a lousy security guard post, so what chance does he have until he takes such a job? It’s as though one pilot fish has convinced the shark to eat his predecessor in order to replace him. Their cutthroat actions are those of a capitalist society that has made everyone desperate to accumulate more wealth, to survive and prosper, even if it means sacrificing your morality or willfully ignoring the humanity of others to attain it. Thus, the lower classes have no choice but to engage in a parasitic relationship with the more prosperous. But opportunistic as the Kims may seem, the Parks, too, are parasites, feeding off the less fortunate to supply themselves with an outsourced lifestyle.

Bong’s tone in the film’s first half has a comic quality, as the Kims’ home invasion of sorts amounts to a mischievous occupation by a family of tricksters. Without beating his ethical drum too loudly, Bong allows the characters to enter a situation of class division that never settles into a routine and avoids becoming a stale sociopolitical platform. Instead, Parasite urgently proceeds into an unforeseeable direction, hinted at by the strange behavior of the Parks. Ominous signs point to something disturbing in the Park household, with a vague allusion to a past trauma and Mr. Park’s controlling attitude, hinted at by Mrs. Park’s “deadly serious” fear of him (she jokes at one point that she’ll be “hanged and quartered” if her husband discovers a troublesome secret). Ki-taek notes of Mrs. Park, “She’s rich but nice.” Seeing the pretense of Mrs. Park’s behavior, Ki-taek’s wife corrects him, “She’s nice because she’s rich.” What might have been the telltale signs that the film would devolve into a macabre chiller prove to be the characteristics of another class—people far removed from others outside of their economic bubble, like aliens from another planet. Bong’s careful gradation of his characters allows for moments where the Parks talk about the smell of their new employees, how they all have the same scent of “old radishes” that Mr. Park associates with people who ride the subway. Ki-taek’s sudden self-consciousness grows into a hatred of how such remarks fuel feelings of inadequacy.

Bong’s tone in the film’s first half has a comic quality, as the Kims’ home invasion of sorts amounts to a mischievous occupation by a family of tricksters. Without beating his ethical drum too loudly, Bong allows the characters to enter a situation of class division that never settles into a routine and avoids becoming a stale sociopolitical platform. Instead, Parasite urgently proceeds into an unforeseeable direction, hinted at by the strange behavior of the Parks. Ominous signs point to something disturbing in the Park household, with a vague allusion to a past trauma and Mr. Park’s controlling attitude, hinted at by Mrs. Park’s “deadly serious” fear of him (she jokes at one point that she’ll be “hanged and quartered” if her husband discovers a troublesome secret). Ki-taek notes of Mrs. Park, “She’s rich but nice.” Seeing the pretense of Mrs. Park’s behavior, Ki-taek’s wife corrects him, “She’s nice because she’s rich.” What might have been the telltale signs that the film would devolve into a macabre chiller prove to be the characteristics of another class—people far removed from others outside of their economic bubble, like aliens from another planet. Bong’s careful gradation of his characters allows for moments where the Parks talk about the smell of their new employees, how they all have the same scent of “old radishes” that Mr. Park associates with people who ride the subway. Ki-taek’s sudden self-consciousness grows into a hatred of how such remarks fuel feelings of inadequacy.

But then, there is a troubling secret beneath the surface of the Park home. A sudden turn in the film arrives around the midpoint in Parasite, when the Parks leave on a camping trip and the Kims unwind in the extravagant, minimalist house. They drink expensive booze and chow-down on snacks, feeling “cozy” in their new space. But the return of the former housekeeper upsets their homey little scene. She has not returned for revenge or anything so obvious; rather, she has come to reclaim her husband, who has long evaded debt collectors by hiding in a frightening concrete sub-basement, constructed in secret by the original starchitect-owner, Namgoong, as a shelter in case of an attack by North Korea. Another parasite, Chung-sook’s husband, has lived down there for years, surviving on secret deliveries of food and supplies by his wife. The idea cannot help but bring to mind Jordan Peele’s Us from earlier this year, where a forgotten world of underground doubles emerges from below to take over the world they were supposed to control. Although, Bong’s film situates itself in the real world, where the chasm between the rich and poor continues to extend. The approach is no less thrilling, however, as the Kim family must scramble to prevent the former housekeeper from exposing them, while the space below the house serves a kind of situational timebomb.

Bong’s deft touch as a filmmaker never forgets the emotional, purely entertaining stakes, though his formal skill is that of a mathematical technician who always knows where to place the camera. Parasite’s careful ratcheting of tension shifts the material into a Hitchcockian suspenser, where the Kims attempt to keep another secret from the Parks—they’ve now confined the housekeeper and her husband in the sub-basement. Hong Kyung-pyo’s cinematography glides the camera around the elaborate sets, built by production designer Lee Ha-jun, so convincing in their construction that the viewer would assume the locations were real. Instead, Bong’s vision is at once intentional and chambered, each camera movement and angle the approach of a cinematic tactician. Subtle, calculated imagery such as eyes peering out from a stairway or the Kim family hiding beneath a large table as the Parks sleep on a nearby couch leave the viewer in breathless suspense, while they’re also “so metaphorical.” Likewise, so is Bong’s script, as when Mr. Park compliments his new driver for not “crossing the line”—an imaginary divide between the classes, which Bong indicates in visual space. And while often such elaborate premeditation can result in a feeling of formal coldness, Parasite develops its characters with humor and humanity in a way that recalls Alfred Hitchcock or Brian De Palma.

Bong’s rare talent at supplying a purely entertaining structure around which he tells a socially relevant story has been his approach to The Host, Snowpiercer, and Okja. Other filmmakers may reduce the meaning of their entertainments to subtext, but Bong interlinks text and scenario in inescapable, confronting ways that might have been more easily disguised by the science-fiction trappings of those earlier titles. Consider Parasite’s final scenes, where Ki-taek is literally confined to the lower depths of the Parks’ home, unable to leave both because of his station and the events of the film’s violent, shocking climax. Bong allows us to believe, albeit briefly, that Ki-woo might do the impossible: go to college, become a success, and find himself able to buy the Parks’ home to rescue his father. “All I need to do is earn money,” Ki-woo says in a letter, as if it were just that easy. But the sobering reality is that all the planning in the world won’t matter in a world designed to repress those of the Kim family’s class. Ki-taek admits earlier in the film, “I have no plan”—a sad admission that acknowledges how he can never control his life in the manner of the moneyed Parks. From this realization, Ki-taek’s despair propels the climactic moment, where Mr. Park’s crude statement (“You’re getting paid extra”) becomes the last straw. Bong avoids demonizing the rich, but he portrays them as cruelly unaware members of a society that rarely acknowledges the underclass.

Bong’s rare talent at supplying a purely entertaining structure around which he tells a socially relevant story has been his approach to The Host, Snowpiercer, and Okja. Other filmmakers may reduce the meaning of their entertainments to subtext, but Bong interlinks text and scenario in inescapable, confronting ways that might have been more easily disguised by the science-fiction trappings of those earlier titles. Consider Parasite’s final scenes, where Ki-taek is literally confined to the lower depths of the Parks’ home, unable to leave both because of his station and the events of the film’s violent, shocking climax. Bong allows us to believe, albeit briefly, that Ki-woo might do the impossible: go to college, become a success, and find himself able to buy the Parks’ home to rescue his father. “All I need to do is earn money,” Ki-woo says in a letter, as if it were just that easy. But the sobering reality is that all the planning in the world won’t matter in a world designed to repress those of the Kim family’s class. Ki-taek admits earlier in the film, “I have no plan”—a sad admission that acknowledges how he can never control his life in the manner of the moneyed Parks. From this realization, Ki-taek’s despair propels the climactic moment, where Mr. Park’s crude statement (“You’re getting paid extra”) becomes the last straw. Bong avoids demonizing the rich, but he portrays them as cruelly unaware members of a society that rarely acknowledges the underclass.

Though Bong calls Parasite a “tragicomedy” and layers the material with lively humor and his signature tonal playfulness, it’s also his most furious and most fatalistic picture to date. But limiting this film to any genre definition defies the uniqueness of Bong’s filmmaking—at once laugh-out-loud funny and capable of inducing gasps, delightfully engaging yet unflinching in its social critique. Still, Parasite is Bong’s most compassionate and harrowing study of contemporary powerlessness. His other films have featured characters capable of improving their class conditions by some small, hopeful measure—the mourning father in The Host who adopts a homeless child; the escape from the train in Snowpiercer; the survival of the superpig in Okja. But the final moments here articulate Bong’s sense that the economic hierarchies that constitute the foundation of a capitalistic society will remain in place. Moreover, Bong’s other films have handled these themes in the context of genre-inflected worlds, elaborate and comparatively escapist, but with Parasite, he confronts our modern-day dystopia that, if portrayed in a film decades ago, might not look so different than a work of science-fiction. The deep passion he feels for his subject enriches every frame of this outstanding film, a work of stealth and vision marked by its melancholy and rage.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review