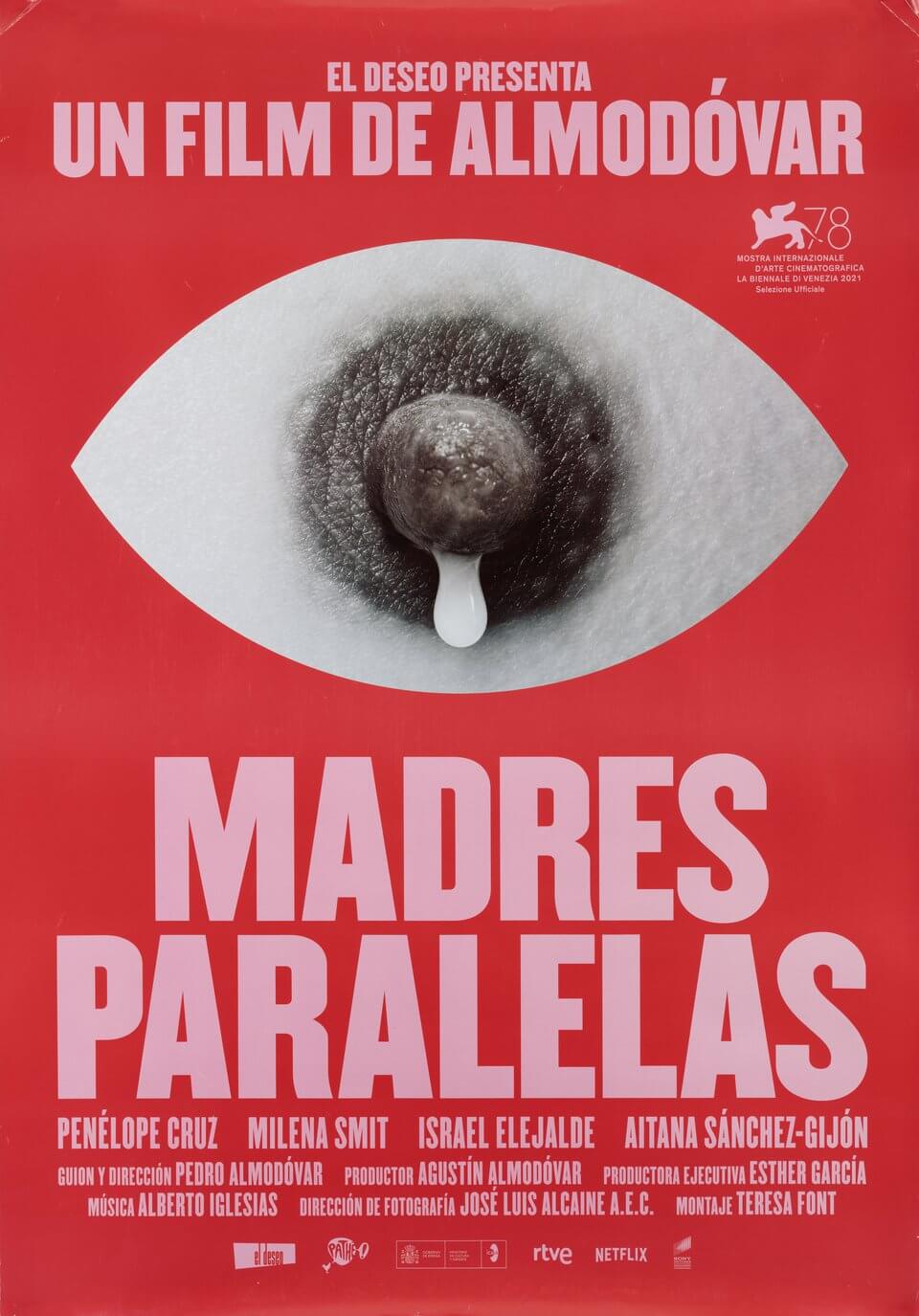

Parallel Mothers

By Brian Eggert |

Pedro Almodóvar’s films radiate empathy. No matter how his characters transgress convention, pursue desire, or betray themselves and others, the Spanish filmmaker accepts their complexity and motivations without judgment. His boundless ability to convey the depth of his characters marks his films, even his most irreverent comedies, with an entrenched humanism. Women usually take center stage in Almodóvar’s films, many of them based on his mother. The “chicas Almodóvar” have a legacy unto themselves: Carmen Maura, Marisa Paredes, Rossy de Palma, Lola Dueñas, Victoria Abril, Julieta Serrano, and Chus Lampreave. For his latest act, he has conjured an incredible performance out of Penélope Cruz, his late-career muse, in Parallel Mothers (Madres paralelas), his twenty-second feature. Women again propel the story, with Cruz and newcomer Milena Smit playing characters who exude power and fragility while representing a national conversation about Spanish history. Almodóvar crafts a heartrending drama about a mothering impulse to treat wounds and nurture a healthy future, leading to a conversation about his country’s Civil War and Francisco Franco’s dictatorship.

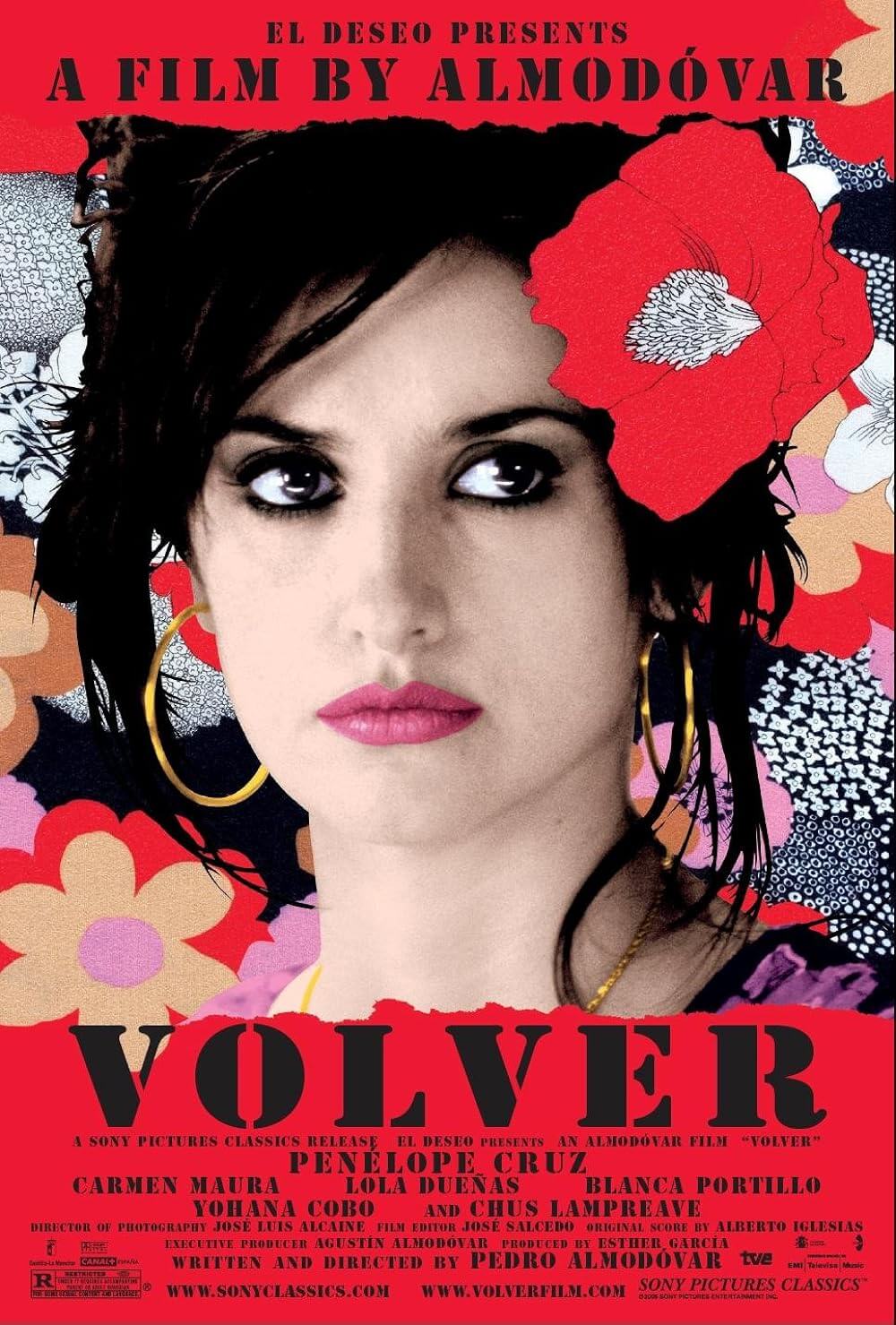

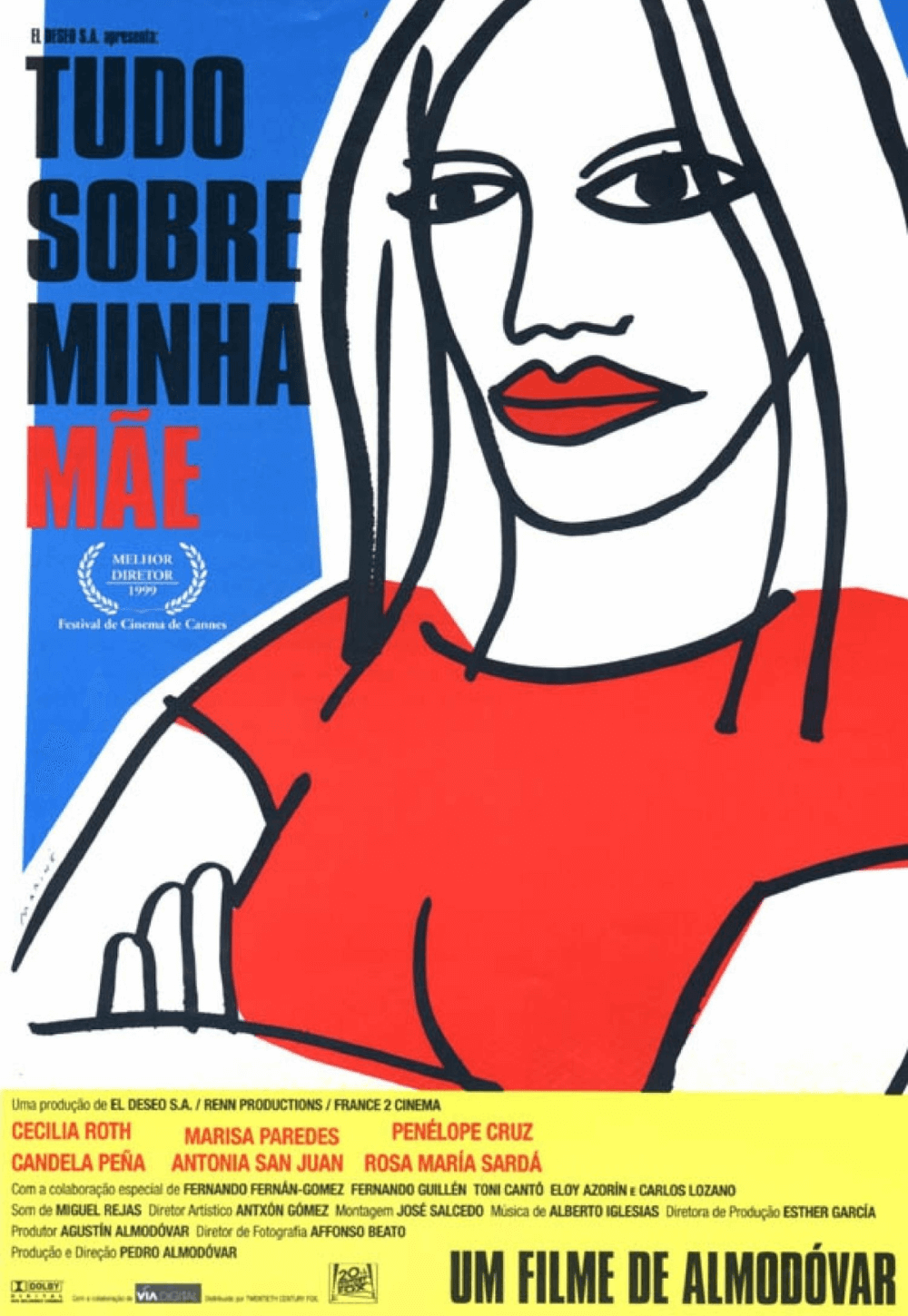

Parallel Mothers marks the first time Almodóvar has confronted Franco and Spain’s history directly. His earliest films actively ignored the past, positing a liberalized and radically transgressive version of Spain as though Francoism had never existed. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, his films remarked on Francoism in passing or dealt with the details of history in metaphorical terms—often by portraying stories of personal trauma. Live Flesh (1997) features a character born on the last night of a Franco-ordered state of emergency, which acts like a bad luck magnet for the remainder of his life. Bad Education (2004) interrogates the ecclesiastical sexual abuse, cover-ups, and repressive Francoist culture using flashbacks and a film-within-a-film device. Arguably his best film, Volver (2006) acknowledges that Spain’s history is full of buried secrets and repressed family traumas, and gradually, its characters uncover them in the form of collective therapy. Almodóvar’s career-long path has gone from defying the past to healing the national psyche through catharsis.

Almodóvar’s new film has the most in common with Volver, and not merely because it also stars Cruz. Both films contain trips from the city to the country in a symbolic voyage into the past, where historical trauma has been literally buried. In Parallel Mothers, Cruz plays Janis, a photographer whose great-grandfather was among the nearly 200,000 victims of Franco’s White Terror at the start of the Spanish Civil War—the exact figure of death remains unknown, as hundreds of unmarked graves around Spain contain the bodies of dissenters (leftists, gay people, Protestants, etc.). Many Spaniards would prefer to let the past rest, but Janis (and thus Almodóvar) recognizes that exhuming these gravesites can have a psychological healing effect. For those with family members who went missing or became victims of Franco’s political executions, the Civil War never ended. And so, after overseeing a photoshoot of Arturo (Israel Elejalde), a forensic anthropologist who specializes in such excavations, Janis asks if he will take on the project of unearthing her great-grandfather’s unmarked gravesite in the country. Arturo agrees to help, assuming he can get the project funded.

At the same time, Janis launches into an affair with Arturo, a married man. Apart from a brief peek in the bedroom, Almodóvar shoots their lovemaking by floating the camera outside of Janis’ apartment, focusing on an open window and the thin curtain blowing about—a moment given conspiratorial undertones from the Hitchcockian score by Alberto Iglesias. Sure enough, a comical cut shows the result: a nine-months-pregnant Janis prepares for labor in a maternity hospital, where she shares a room with the teenage Ana (Smit). Their children will be born on the same day, almost simultaneously. Both women will have to raise their children alone. Janis has broken off her relationship with Arturo, who is not prepared for children with another woman. “I absolve you of all responsibility,” she tells him, eager to have a baby after having given up on the prospect. Ana has only her mother, Teresa (Aitana Sánchez Gijón), who has finally found her voice as a stage actress and remains more interested in her first significant role than her new grandchild. Ana, a gang-rape victim and uncertain of her child’s parentage, receives no support from her father, who lives in the country and shames her for her victimization. For Ana, the country reminds her of an experience she would rather forget.

At the same time, Janis launches into an affair with Arturo, a married man. Apart from a brief peek in the bedroom, Almodóvar shoots their lovemaking by floating the camera outside of Janis’ apartment, focusing on an open window and the thin curtain blowing about—a moment given conspiratorial undertones from the Hitchcockian score by Alberto Iglesias. Sure enough, a comical cut shows the result: a nine-months-pregnant Janis prepares for labor in a maternity hospital, where she shares a room with the teenage Ana (Smit). Their children will be born on the same day, almost simultaneously. Both women will have to raise their children alone. Janis has broken off her relationship with Arturo, who is not prepared for children with another woman. “I absolve you of all responsibility,” she tells him, eager to have a baby after having given up on the prospect. Ana has only her mother, Teresa (Aitana Sánchez Gijón), who has finally found her voice as a stage actress and remains more interested in her first significant role than her new grandchild. Ana, a gang-rape victim and uncertain of her child’s parentage, receives no support from her father, who lives in the country and shames her for her victimization. For Ana, the country reminds her of an experience she would rather forget.

Iglesias’ music imbues Parallel Mothers with a touch of suspense as Janis, noting the darker skin tone of her newborn girl, questions if the child belongs to her—Arturo doesn’t believe the child belongs to him either. Almodóvar doesn’t reveal the extent of Janis’ suspicions until she orders a maternity test kit. The negative result shocks her, and the aftermath almost plays like a thriller. Even while feeling fearless yet raw, Cruz’s performance carries an air of mystery. Janis makes a hasty call to an attorney and suddenly changes her phone number. What does she suspect? And then, in one of Almodóvar’s whimsical coincidences, she runs into Ana, who has since lost her baby tragically and suddenly to cot death (SIDS). Frustrated with her distracted Irish au pair and recognizing Ana’s situation, Janis proposes that Ana become her live-in nanny.

From there, the two develop a curious relationship that goes beyond employer-employee; they form a makeshift mother-daughter pair as Janis teaches Ana to cook and make a home. They also become lovers, which complicates matters further. Then again, Almodóvar never judges the thornier dimensions of their relationship. He accepts how Janis and Ana change together, regardless of how outsiders might psychoanalyze or label the relationship. When Janis deceives Ana into taking a maternity test, the results show Ana gave birth to Janis’ daughter—and that the hospital must have accidentally switched their babies while they were under observation. Although Ana tries to move on from what she believes to be her child’s death, she still experiences grief. Janis cannot continue covering up her baby’s true identity and decides to share the results of the maternity test with Ana, even if it means that she’ll lose the baby with which she has a motherly bond.

The film’s primary story about mothers and parentage becomes analogous to the subplot about Janis and Arturo working to unearth a mass grave—both require that Janis confront a devastating truth. In terms of Spain confronting its past, that’s easier said than done. In 1977, the Spanish parliament enacted an Amnesty Law, instituting a “pact of forgetting,” a legal position that shielded the Spanish State criminals from punishment for their crimes against humanity. Though challenged over the years, the law remains and contributes to the nationalized amnesia of the traumas under Franco’s regime. In 2007, Spain’s government launched the Historical Memory Law to better acknowledge the victims of Francoism. Unfortunately, politics have prevented the new law from making much headway. The conservative right and liberal left have criticized the limited law, which “broadens the rights and establishes measures in favor of those who suffered persecution or violence during the Civil War and the Dictatorship.” The conservative Popular Party argues that the law wasn’t keeping with Spain’s democratic progress and pointlessly dug up historical atrocities. The Republican left feels the law fails to address the extent of Franco’s victims adequately. And since the Amnesty Law still stands, any subsequent attempt to remember becomes a complicated process of confrontation.

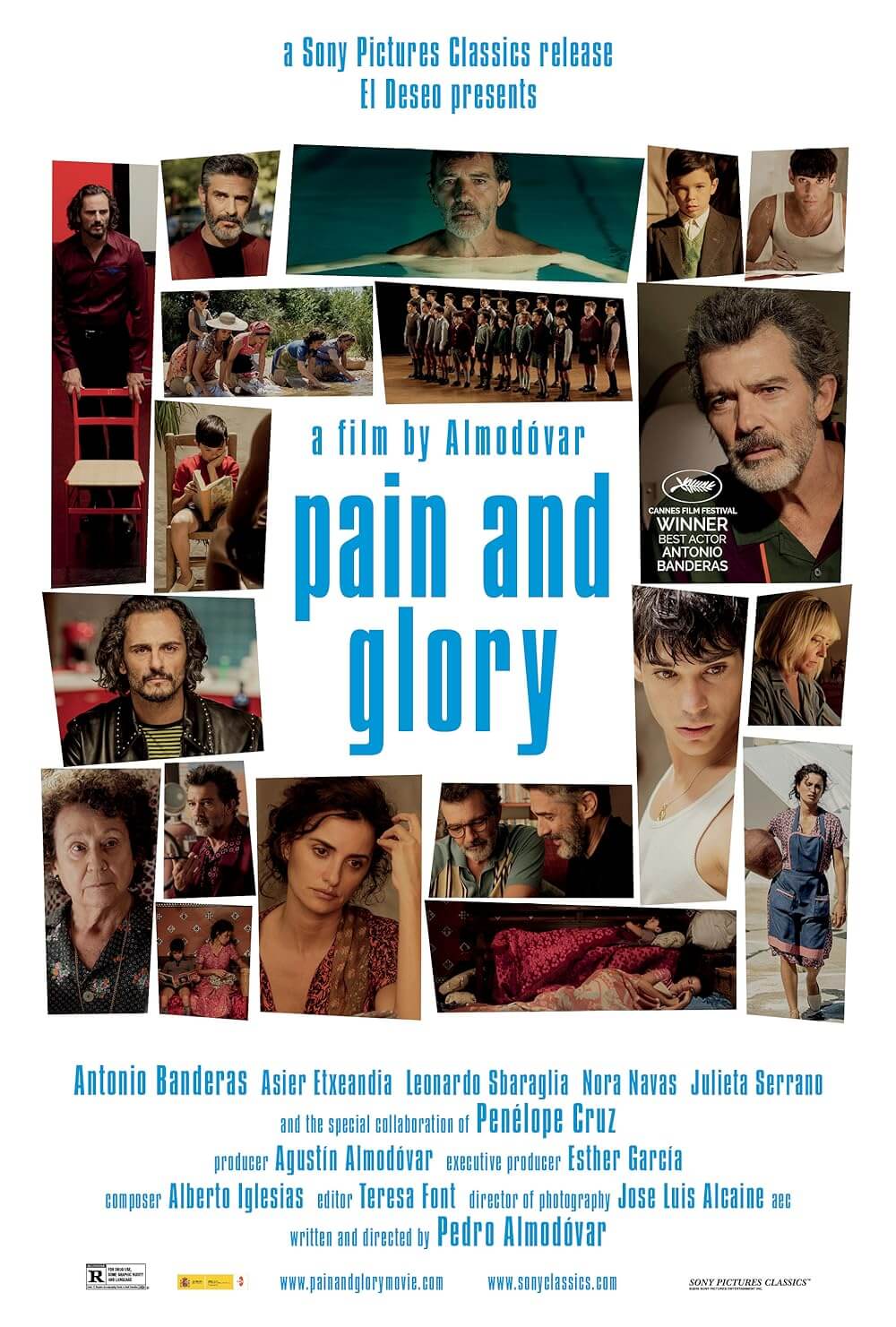

Almodóvar’s film sees the necessity in examining the past to fully process the Civil War. It’s not a matter of opening old wounds but finally allowing the still-open wounds to heal. Franco’s decades in power reshaped an untold number of families, and most of the characters and filmworkers involved in Parallel Mothers have family members or know someone who was affected. Although the director often tells stories about characters who must investigate their pasts—his characters have histories filled with painful memories, forbidden desires, and deadly secrets—he usually addresses Franco in figurative terms. His journey from ignoring the problem to symbolic references to stark confrontation has been a long road. Over forty years, his films have gone from wildly flamboyant and transgressive, filled with deviations and rebellious asides, to a gradually more serious and contemplative aesthetic. Even Almodóvar’s last film, the relatively austere personal meditation Pain and Glory (2018), contains structural elements that play with the viewer’s understanding of what is shown—a memory, a film-within-a-film, or the narrative proper. Besides a flashback and heavy fades that indicate longer passages in time, Parallel Mothers is among the director’s most straightforward films.

Almodóvar’s film sees the necessity in examining the past to fully process the Civil War. It’s not a matter of opening old wounds but finally allowing the still-open wounds to heal. Franco’s decades in power reshaped an untold number of families, and most of the characters and filmworkers involved in Parallel Mothers have family members or know someone who was affected. Although the director often tells stories about characters who must investigate their pasts—his characters have histories filled with painful memories, forbidden desires, and deadly secrets—he usually addresses Franco in figurative terms. His journey from ignoring the problem to symbolic references to stark confrontation has been a long road. Over forty years, his films have gone from wildly flamboyant and transgressive, filled with deviations and rebellious asides, to a gradually more serious and contemplative aesthetic. Even Almodóvar’s last film, the relatively austere personal meditation Pain and Glory (2018), contains structural elements that play with the viewer’s understanding of what is shown—a memory, a film-within-a-film, or the narrative proper. Besides a flashback and heavy fades that indicate longer passages in time, Parallel Mothers is among the director’s most straightforward films.

Still, the film is unquestionably the work of Almodóvar, who labors over every detail. Given that he works behind the shield of El Deseo, the production company he started with his brother Agustín, Almodóvar controls everything from his shooting schedule to the décor. His interiors and costumes pop with color, dynamic contrasts, and textures, bringing modest rooms such as Janis’ kitchen to vivid life. Parallel Mothers looks like a highly composed and considered visual space that permeates a vibrancy into the characters and scenario from one moment to the next. He even controls the marketing: the film’s initial poster featured a stark red background in which an eye-shaped space revealed a woman’s nipple, and a drop of mother’s milk, in monochrome—evoking a mother’s tear over the bloody trauma of the past. The poster caused some mild (and absurd) controversy online, all the while ensuring word about the film spread even further. In each decision, Almodóvar applies a master’s intention, making the result a readable and inspired evocation.

As ever, Almodóvar directs his actors in Parallel Mothers to give deeply human performances, just as he wrote them. Cruz, who has acted in seven Almodóvar films since first appearing in Live Flesh, is terrific and full of life here. It might be her greatest performance next to the one in Volver. Almodóvar and Cruz, as director and actor, trust each other entirely, following Janis through a series of decisions that will be painful—the pain of childbirth, the pain of separation, the pain of confronting the past—but necessary. Only someone as strong as Janis could manage them with such fearless grace, and only someone as skilled as Cruz could make her come alive. Without becoming preachy or didactic about its subject, Parallel Mothers addresses Spanish politics and disentangles the nation’s trauma, urging Spain to have the same willingness to endure pain. After all, if every woman avoided childbirth to avoid the pain of labor, society would cease to be. Only through an acceptance of pain comes new life.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review