Reader's Choice

Papillon

By Brian Eggert |

At the penal colony of Saint-Laurent-du-Maroni in French Guiana, the official overseeing solitary confinement makes a rehearsed speech to the new inmate known as Papillon. “We make no pretense of rehabilitation here,” he declares proudly. “We’re not priests; we’re processors. A meatpacker processes live animals into edible ones. We process dangerous men into harmless ones.” In his book Discipline and Punish, Michel Foucault wrote about the prison’s desire for “docile bodies” to be “subjected, used, transformed and improved.” As Foucault detailed, the body’s transformation—or processing—has been an essential component of prison philosophy for centuries. Franklin J. Schaffner’s film of Papillon, based on the account by Henri Charrière, who escaped from Devil’s Island in 1941, follows a character who is not pliable. He refuses to be processed. The film critiques a society, from French penal codes to the larger prison system, that openly endeavors to take away a man’s resolve until he is nothing. But it also portrays one man’s refusal to give in. A condemnation not only of wrongful imprisonment but any imprisonment that seeks to dehumanize, the film is as dogged as its hero.

Steve McQueen stars as Charrière in a performance circumscribed by prison regimentation from the start. The first scenes show him walking down a French street in front of onlookers, making his way alongside dozens of other prisoners toward the ship that will transport him to French Guiana. At the outset, the body of this former safe cracker, who was falsely accused of killing a pimp, becomes an object of disciplinary arrangement. He and other prisoners walk in formation at gunpoint. They board a boat where they sleep in hammocks behind bars and are shackled at night. When they arrive at the penal colony, they take a line formation to receive their prison garb. They will spend their days at hard labor that works the body to exhaustion, sometimes beyond it. The tactic is what Foucault described as “a body manipulated by authority, rather than imbued by animal spirits; a body of useful training.” The prison attempts to build a routine and work the criminality out of these men through punishing labor and physical limitations. Most prisoners try to stay on the guards’ good sides, keep their heads down, and make it out alive (they are told 40% of them will die in the first year). Papillon, so named from the butterfly tattoo on his chest, refuses to submit. His repeated line, “I’m still here, you bastards,” signals his continued defiance—first in solitary confinement and again when he escapes captivity for good in the final scene.

Critic Stephen Farber included Papillon on a list of “male romances” obsessed with masculine camaraderie in the mid-1970s. Although McQueen’s character spends much of the film alone, pacing in his cell, plotting some way to escape—the film spends nearly a half-hour with him in solitary—he’s usually alongside counterfeiter Louis Dega (Dustin Hoffman). Aside from a seemingly endless supply of cash stored in his rectum, Dega also has lasting enemies from the embezzlement scheme that landed him in prison. “Me, they can kill,” Papillon warns. “You, they own.” Both of them need to escape, so they form an unlikely trust. Though, Farber’s suggestion of a homoerotic undercurrent seems broadly attached to this particular story. The film’s portrait of queerness is epitomized by André (Robert Deman), a stereotypical gay character and prison hospital orderly who seduces a guard and escapes alongside Papillon and Dega. And there’s no hint at a sexual relationship between Papillon and Degas; rather, the film reinforces Papillon’s heterosexuality more than once: First, in the presence of a French woman who appears in the first scene in France and again in Papillon’s hallucinations; second, in Papillon’s relationship with a young woman when he briefly escapes to Honduras.

Critic Stephen Farber included Papillon on a list of “male romances” obsessed with masculine camaraderie in the mid-1970s. Although McQueen’s character spends much of the film alone, pacing in his cell, plotting some way to escape—the film spends nearly a half-hour with him in solitary—he’s usually alongside counterfeiter Louis Dega (Dustin Hoffman). Aside from a seemingly endless supply of cash stored in his rectum, Dega also has lasting enemies from the embezzlement scheme that landed him in prison. “Me, they can kill,” Papillon warns. “You, they own.” Both of them need to escape, so they form an unlikely trust. Though, Farber’s suggestion of a homoerotic undercurrent seems broadly attached to this particular story. The film’s portrait of queerness is epitomized by André (Robert Deman), a stereotypical gay character and prison hospital orderly who seduces a guard and escapes alongside Papillon and Dega. And there’s no hint at a sexual relationship between Papillon and Degas; rather, the film reinforces Papillon’s heterosexuality more than once: First, in the presence of a French woman who appears in the first scene in France and again in Papillon’s hallucinations; second, in Papillon’s relationship with a young woman when he briefly escapes to Honduras.

Papillon’s dearth of women and lack of repressed homosexuality brings the central theme, captured by the line “I’m still here,” into focus. The film’s few women serve as objects of fantasy or Otherness (when Papillon is rescued in Honduras, Schaffner shoots the natives with a degree of National Geographic sub-humanity, showing topless women and underage girls is intended as ethnography more than voyeurism). This is to say that all else besides Papillon’s determination to escape remains secondary. Schaffner is more interested in depicting the penal colony’s brutal reality based on his own research and attention to detail in recreating the prison’s layout and conditions. The film’s protracted, measuredly paced runtime of 150 minutes allows the viewer to experience confinement and processing to see what imprisonment takes away. Thus, Papillon is not a three-dimensional character with a rich inner life but one driven by a singular and cinematic cause: escape. McQueen’s presence as a screen icon does the rest.

Even so, Schaffner’s control over the pacing and mood of Papillon is superb. This same quality, so austere and drained of color, would be called out by the film’s detractors who suggested watching Papillon was tantamount to prison time. But that’s precisely the film’s objective, and it succeeds. The screen story covers a 14-year period, and in addition to his slow pacing and long takes, Schaffner finds subtle ways to denote the passage of time without overemphasizing the point. Watch the increasing size of the bald spot on the top of Dega’s head or Papillon’s white linen garb in solitary confinement that is black and tattered by the end of his two years. Jerry Goldsmith’s Oscar-nominated score—the film’s only nomination—feels almost recessive if not altogether absent in most scenes. The most pronounced and expressive moments come when Schaffner alludes to Papillon’s motivations through several dream sequences, experienced when Papillon is at his worst, most desperate moments. He sees bold images of an unfulfilled life, such as parades and an idyllic woman contrasted by a horrific image of himself zombified in a world upside-down. His persistent worry is that he’s led “a wasted life.” His hallucinations suggest that Papillon is compelled by the same rebellious born-free mentality found in counter-culture cinema of the 1960s from Easy Rider (1969) to Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969)—the notion that any manner of containment, be it societal or institutional, is a soul-killer.

Charrière published his self-titled book in 1969, detailing his experience in the notorious French colonial prison system. The best-seller quickly attracted French producer Robert Dorfman, who purchased the rights and began developing the film adaptation alongside Schaffner as his co-producer and director. Schaffner, who had just delivered a couple of Oscar-winning commercial hits with Planet of the Apes (1968) and Patton (1970), set up the project at Allied Artists, a former B-movie production company that had given up its studio facilities and become an import distributor in the 1960s. In the early 1970s, however, Allied Artists returned to original productions with titles like Cabaret (1973) and The Man Who Would Be King (1975). Making Papillon was a risky financial venture for the struggling company, requiring Allied to finance the picture for a total of $15 million for the negative cost (more than twice the original projected cost of $7 million), borrowed at a staggering interest rate of 20%. A sizeable portion of the production, which shot on location in Spain and Jamaica, went to McQueen and Hoffman’s salaries ($2 million for McQueen; $1.5 million for Hoffman). Charrière gave his blessing on McQueen, and though he and Dorfman would have preferred a Frenchman in the role, the filmmakers knew the production needed a bankable Hollywood star to earn a profit.

Charrière published his self-titled book in 1969, detailing his experience in the notorious French colonial prison system. The best-seller quickly attracted French producer Robert Dorfman, who purchased the rights and began developing the film adaptation alongside Schaffner as his co-producer and director. Schaffner, who had just delivered a couple of Oscar-winning commercial hits with Planet of the Apes (1968) and Patton (1970), set up the project at Allied Artists, a former B-movie production company that had given up its studio facilities and become an import distributor in the 1960s. In the early 1970s, however, Allied Artists returned to original productions with titles like Cabaret (1973) and The Man Who Would Be King (1975). Making Papillon was a risky financial venture for the struggling company, requiring Allied to finance the picture for a total of $15 million for the negative cost (more than twice the original projected cost of $7 million), borrowed at a staggering interest rate of 20%. A sizeable portion of the production, which shot on location in Spain and Jamaica, went to McQueen and Hoffman’s salaries ($2 million for McQueen; $1.5 million for Hoffman). Charrière gave his blessing on McQueen, and though he and Dorfman would have preferred a Frenchman in the role, the filmmakers knew the production needed a bankable Hollywood star to earn a profit.

Papillon would be the last screenplay written by Dalton Trumbo before his death in 1976. By the time Schaffner asked Trumbo to contribute to the script, William Goldman (All the President’s Men, 1976) had already worked on three drafts, and Lorenzo Semple Jr. (The Parallax View, 1974) penned another three drafts. Trumbo also had Schaffner’s research about French prison colonies to incorporate, not to mention a much larger role for Hoffman, since Dega was a minor character in the book. After cranking out his own draft, Trumbo was dissatisfied with the outcome and asked Schaffner to consider hiring another writer. Pressed by an impending shoot, Schaffner asked Trumbo to accompany the production instead, during which Trumbo wrote new pages every day and barely kept ahead of the shooting schedule. In Larry Ceplair and Christopher Trumbo’s biography, they suggest Trumbo wasn’t interested in the prison escape adventure qualities of the story; he was drawn to Charrière’s portrait of the system that unjustly locked him away. As one of the Hollywood Ten, Trumbo served eleven months in prison after refusing to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1947 during their probe into communist influence in Hollywood. Given his imprisonment and subsequent blacklisting by the industry, Trumbo doubtlessly identified with Papillon.

With its high price tag, Papillon’s over $22 million in domestic receipts and status as the fourth top earner at the 1973 box office meant the studio barely made a profit. Allied Artists made the most of McQueen’s star status with posters that proclaimed Papillon as “The greatest adventure of escape!”—suggesting fans of McQueen’s performance in John Sturges’ The Great Escape (1963) would be treated with the same but odd balance of fun male camaraderie and grim prison conditions. But audiences expecting a good time at the movies were confronted by an unflinching portrait of Papillon’s experiences. According to many critics, the biggest flaws were Schaffner’s languid pacing and McQueen’s man-of-few-words portrayal that shed little light on Papillon’s inner self. It’s surely one of McQueen’s most serious roles, and the challenging Jamaica shoot delivered obstacles such as torrid weather and temptations for its leading man. Schaffner was forced to dress McQueen in oversized prison garb to hide the extra weight the actor put on from his excessive drinking and constant smoking of Jamaican pot. However, McQueen’s physicality does the picture a service, especially when he and Hoffman wrestle a live crocodile or when McQueen performs his own stunt and leaps off a cliff to freedom in the final scene. Then again, in Papillon’s later scenes that reveal our hero as an older man, McQueen is stiff, unsure how to behave, and too reliant on flashing a grimace of gold and gray teeth.

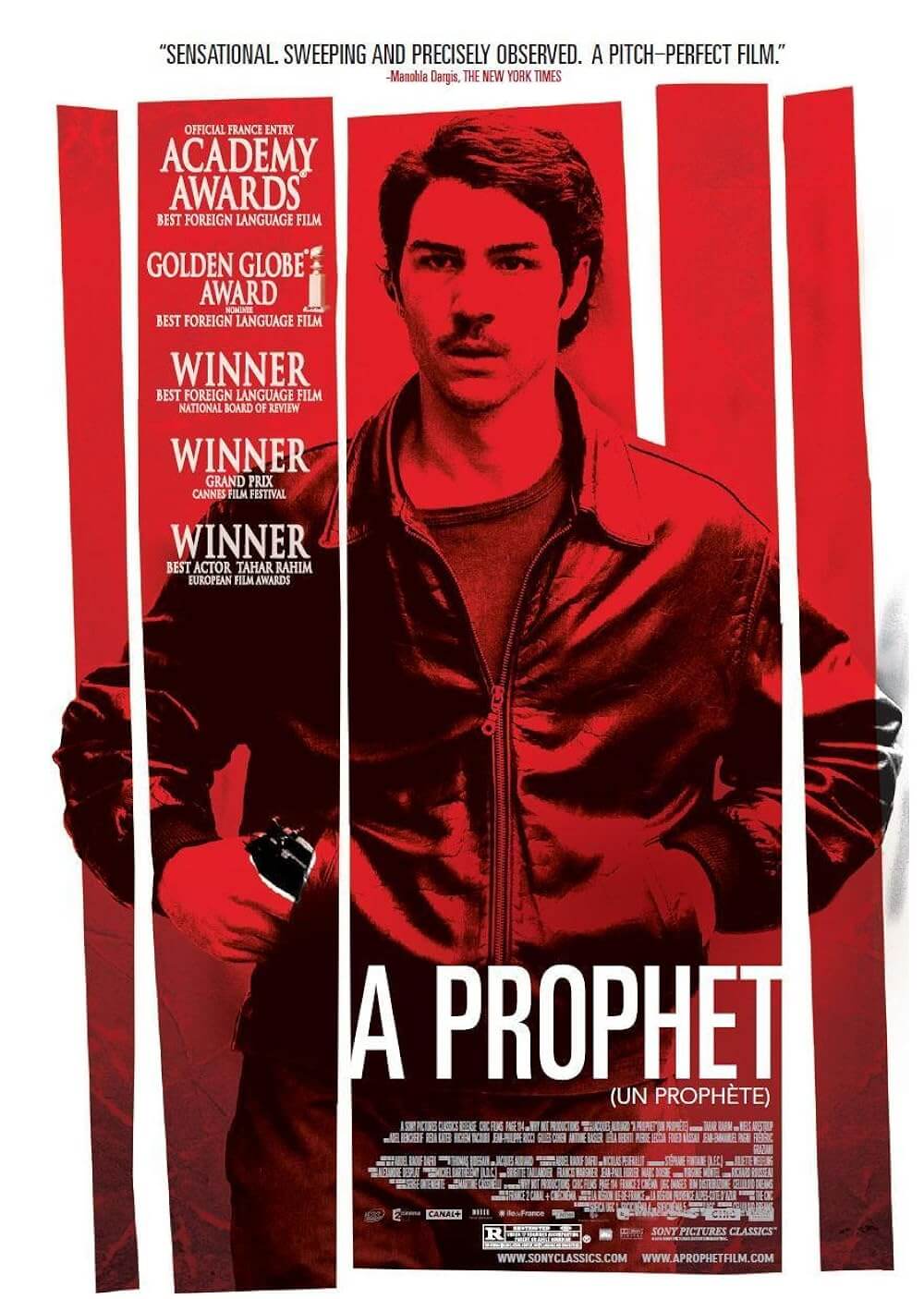

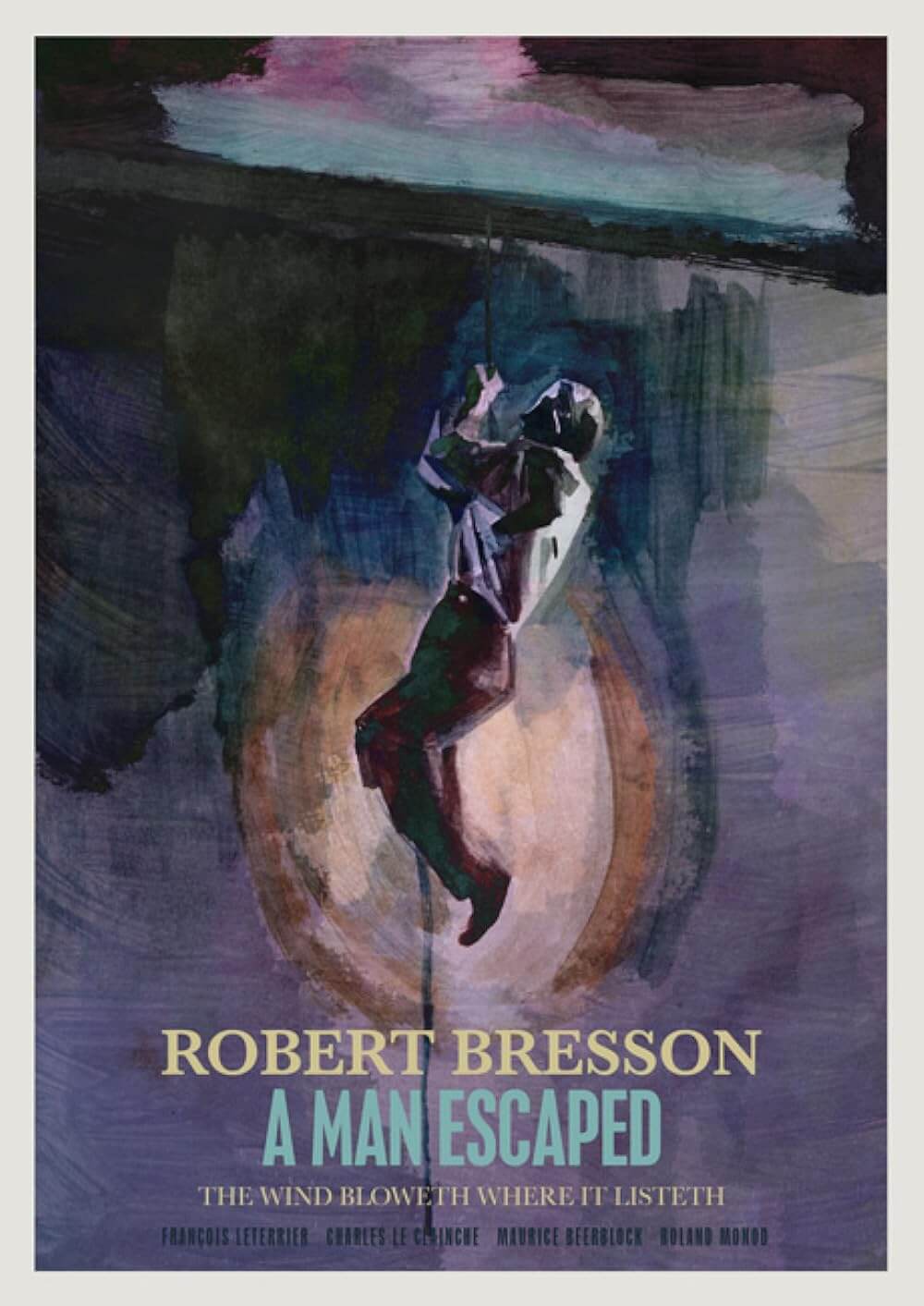

The film’s contemporary critics responded harshly in most cases. Common among the responses were dismissals of the film’s pacing, repetitiveness, and lacking character development. Variety’s staff critic observed, “The oppressive atmosphere is so absolutely established within the first hour of the film that, in a sense, it has nowhere to go for the rest of the time.” Roger Ebert dismissed the film for the same reasons, albeit more glibly, noting that “Hoffman is using his limp again from Midnight Cowboy, and McQueen squints into the sun a lot, and that’s about it.” It was the production’s Hollywoodness that Time critic Richard Corliss objected to: “The slickness of his work vitiates any attempt to take Papillon with entire seriousness.” Critics seemed to miss that Schaffner intentionally dragged out the proceedings to give the viewer some small taste of prison life. Masters such as Robert Bresson in A Man Escaped (1956) to Jacques Becker in Le Trou (1960) have sought to transport viewers into prison, but those are French arthouse pictures, not Hollywood “adventures” with inbuilt expectations for entertainment. Escapism is the last thing Papillon supplies. Even though McQueen’s character frees himself from Saint-Laurent-du-Maroni and later Devil’s Island, the viewer never sees him reach land or reconnect with the woman spied in his dreams. Schaffner delivers a film with a massive scope, A-list stars, and expensive production values, but his story has more in common with Bresson or Becker than Sturges.

The film’s contemporary critics responded harshly in most cases. Common among the responses were dismissals of the film’s pacing, repetitiveness, and lacking character development. Variety’s staff critic observed, “The oppressive atmosphere is so absolutely established within the first hour of the film that, in a sense, it has nowhere to go for the rest of the time.” Roger Ebert dismissed the film for the same reasons, albeit more glibly, noting that “Hoffman is using his limp again from Midnight Cowboy, and McQueen squints into the sun a lot, and that’s about it.” It was the production’s Hollywoodness that Time critic Richard Corliss objected to: “The slickness of his work vitiates any attempt to take Papillon with entire seriousness.” Critics seemed to miss that Schaffner intentionally dragged out the proceedings to give the viewer some small taste of prison life. Masters such as Robert Bresson in A Man Escaped (1956) to Jacques Becker in Le Trou (1960) have sought to transport viewers into prison, but those are French arthouse pictures, not Hollywood “adventures” with inbuilt expectations for entertainment. Escapism is the last thing Papillon supplies. Even though McQueen’s character frees himself from Saint-Laurent-du-Maroni and later Devil’s Island, the viewer never sees him reach land or reconnect with the woman spied in his dreams. Schaffner delivers a film with a massive scope, A-list stars, and expensive production values, but his story has more in common with Bresson or Becker than Sturges.

A 2017 remake starring Charlie Hunnam and Rami Malek in the McQueen and Hoffman roles, respectively, belongs in the category of “Why did Hollywood do that?” It features none of Schaffner’s artistry and a predominance of gloss. Alternatively, Papillon should be seen as a rare fusion of detailed filmmaking and Hollywood resources. If the noted criticisms about McQueen’s old man performance remain true, the film’s remainder is an immersive, engrossing experience—unpleasant, yet admirably entrenched compared to standard prison adventure pictures. Rather, its ambitions reach beyond audience titillation. Seeing Papillon placed on the notorious Devil’s Island, one cannot help but think of the Dreyfuss Affair, in which a Jewish captain of the French Army was wrongly convicted of treason and sent to the same island in a scandal motivated by antisemitism and political conspiracy. However, Albert Dreyfuss supplied a noble hero unjustly imprisoned. In contrast, the fight for freedom in Papillon offers little consideration for what landed its protagonist in prison or the corrupt system that condemned him. Instead, it portrays with Foucauldian detail the prison’s attempt to regiment the body and control the spirit. For some, Papillon’s endurance proves too long and the film too confining—too close to actual prison time. For others, Schaffner’s form-follows-function approach makes one appreciate freedom, and understand Papillon’s motivations, all the more.

(Editor’s Note: This review was commissioned on Patreon. Thank you for your support, Ron!)

Bibliography:

Ceplair, Larry, and Christopher Trumbo. Dalton Trumbo: Blacklisted Hollywood Radical. The University Press of Kentucky, 2015.

Eliot, Marc. Steve McQueen: A Biography. Three Rivers Press, 2012.

Farber, Stephen. “The Vanishing Heroine.” The Hudson Review, vol. 27, no. 4, 1974, pp. 570–576. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3850358. Accessed 9 April 2021.

Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Pantheon Books, 1977.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review