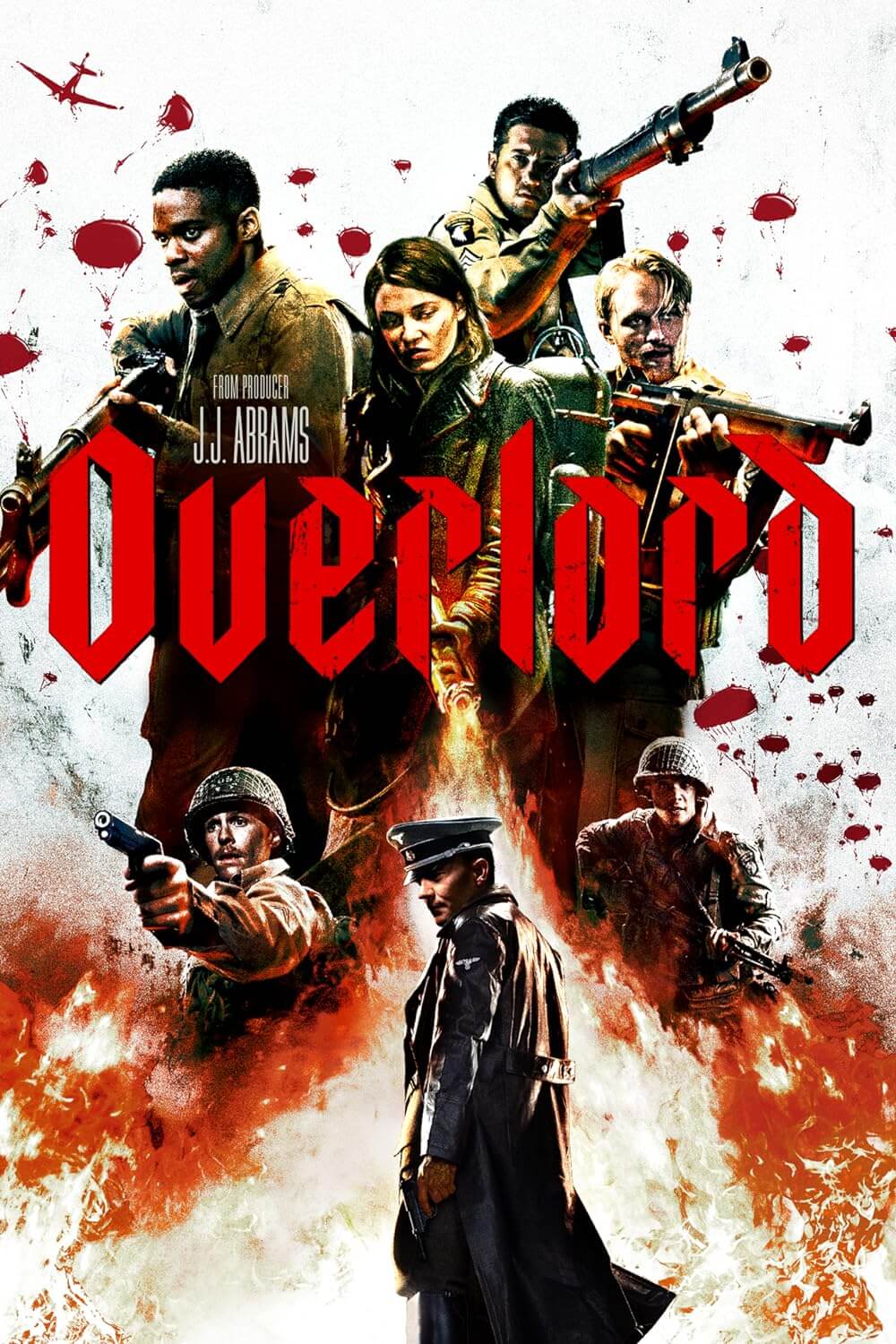

Overlord

By Brian Eggert |

Overlord has no right being so good. It’s the stuff of vulgar B-movies and exploitation, in that it concerns a group of American soldiers in World War II who discover a frightening Nazi plot to engineer undead super-soldiers. But the screenplay by Billy Ray (Captain Phillips) and Mark L. Smith (The Revenant) treats the material with a respect for setting and character that is rarely achieved, or aspired to, by such kitschy subject matter. Set just hours before the landings of Operation Neptune, the Allied invasion of Normandy on D-Day, the story follows a squadron of paratroopers on a vital mission to destroy a Nazi radio tower in a crumbling French village. As the film’s characters cross the war-torn landscape, revealing their layers and bonding along the way, the viewer cannot help but think of Steven Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan (1998). And sure enough, Overlord maintains the integrity of an actionized war thriller for about two-thirds of its runtime, before its eventual transition into something resembling the disembodied horrors of Stuart Gordon’s Re-Animator (1985). By the time the film introduces an absurd element in the form of undead Nazi soldiers, it has already won over the audience with a measure of intelligence and well-developed characters.

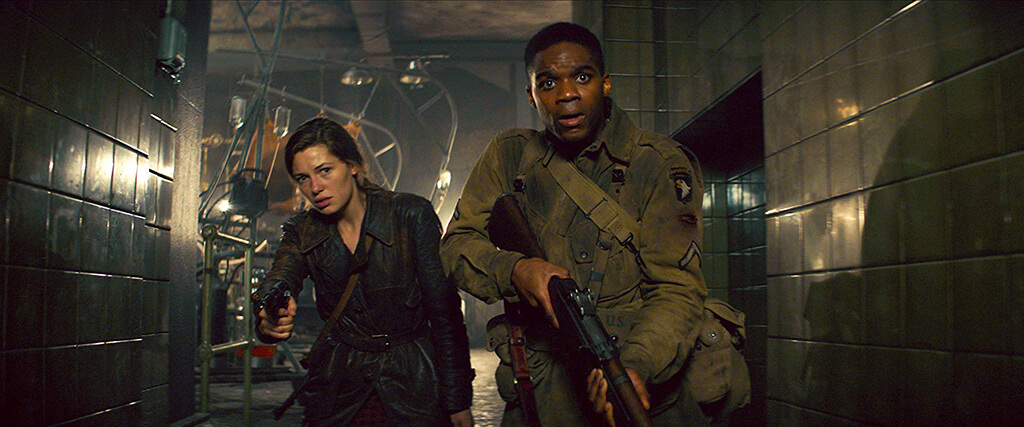

After their plane goes down in a tense night sequence involving exploding aircraft and bullets streaming by like flashes of light, a few American survivors regroup to approach their target. They’re headed by Corporal Ford (Wyatt Russell), the ranking officer and explosives expert whose seen-it-all experience has shaped him into a hardened realist. Our perspective, however, is aligned with Private Boyce (Jovan Adepo), fresh out of boot camp and decidedly unenthusiastic about the prospect of killing, Nazis or otherwise. There’s also Private Tibbet (John Magaro), an aggressive gasbag with a cruel streak; Private Rosenfeld (Dominic Applewhite), a scrawny Jewish-American who worries what will happen if the Nazis discover his last name; and Chase (Iain De Caestecker), a soldier determined to document his wartime exploits on his beloved camera. Together, they head toward their destination and encounter a young French woman, Chloe (newcomer Mathilde Olivier, excellent), who gives them a temporary base of operations in her home—inhabited by her kindly little brother Paul (Gianny Taufer) and an unseen aunt whose horrific-sounding cough alludes to a ghoulish sickness.

With just a few short hours to take out the radio tower, the soldiers learn that a Nazi officer named Wafner (Pilou Asbaek) presides over the French town. He has a distasteful agreement with Chloe, subjecting her to seedy sexual advances in exchange for leniency. It’s kept her alive thus far; although Boyce, ever righteous, cannot stand by and watch Wafner’s version of “grab ’em by the pussy.” And so, Overlord quickly becomes a film led by marginalized heroes, a woman and an African American man. Eventually, Boyce squirrels his way into the Nazi compound beneath the local church, where he discovers the mad scientist, Dr. Schmidt (Erich Redman), has conducted twisted experiments on the locals. Whereas history shows us that Nazis performed experimental and exploratory surgeries on victims in concentration camps, the film turns that notion into a source of fantastical horror—Schmidt has found a way of reanimating dead flesh, as “the thousand-year Reich needs thousand-year soldiers.” But as Boyce witnesses, Schmidt’s efforts have resulted only in abominations: tomblike cells hold slimy, screeching things; large rubber bags incubate writhing bodies for some unholy purpose; a woman’s cranium and spinal column have been fastened into clamps, and yet the detached head speaks the desperate line, “S’il vous plaît.”

Movies and video games have spliced together Nazis and the supernatural for decades. Nazis don’t really need a fantastical element to make them worse, but adding another layer of uncanny power to their baseline evil enhances their malevolence, even as it often robs them of their inherent, scarier human monstrosity. The sociopolitical layers to Nazis—antisemitism, genocide, political nationalism—often submit to the nature of the monster in cases like The Frozen Dead (1966), where Dana Andrews plays a Third Reich doctor who has frozen hundreds of Nazis and plans to unthaw them in the 1960s as undead slaves. Shock Waves (1977) and Zombie Lake (1981) each featured Nazi-zombies emerging from under the water, while Dead Snow (2009) and its sequel considered Nazi corpses that rise on a wintry mountain. In the superhero genre, Hellboy (2004) introduced Nazi occultists that paired fascism with other-worldly dark magic, and Captain America: The First Avenger (2011) found Nazis exploring a chemical solution to the Übermensch. Video game franchises from Call of Duty to Wolfenstein also use Nazi-monsters in a first-person shooter format to enhance one’s enjoyment of annihilating bad guys.

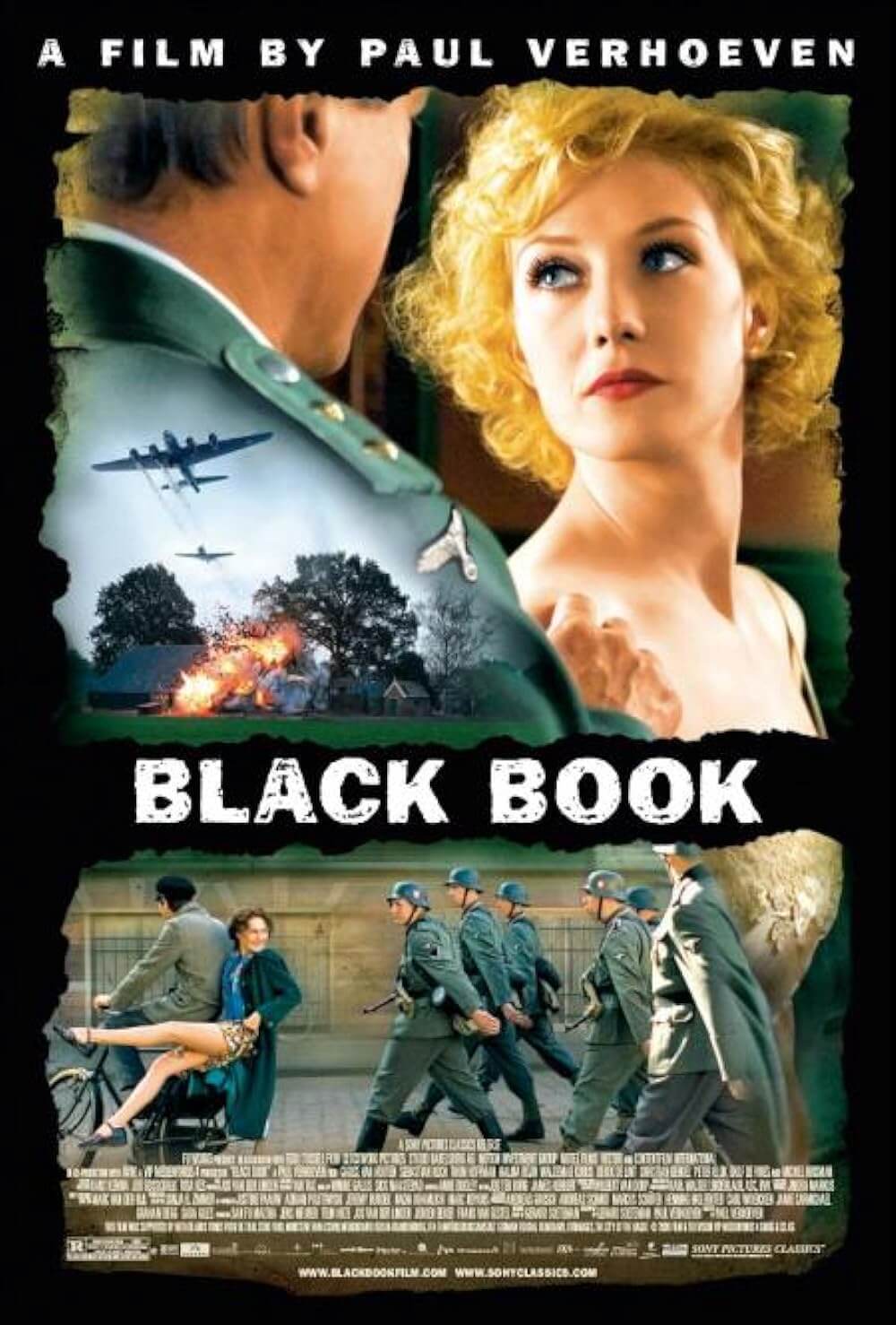

But none of these examples treat Nazi-monsters as anything more than a novelty, whereas Overlord maintains a self-seriousness, regardless of its potential to become mere schlock. In his second feature (after 2014’s Son of a Gun), director Julius Avery demonstrates complete control over his film’s shifting tones, situating the proceedings firmly in the World War II actioner, in that its entertainment value does not ignore Nazi atrocities. Avery’s blend of adventure and wartime barbarity recalls Paul Verhoeven’s great Black Book (2006) in that way. When the moment that introduces a horror element arrives, the film doesn’t shift genres—as, say, From Dusk Till Dawn (1996) switches gears from Tarantino-esque bank robbers into a go-for-broke vampire movie. Instead, except for some of Wafner’s dialogue in the finale, Avery treats the material as though Nazi-zombies are simply a wrinkle in the larger mission to destroy the radio tower. The film never develops an inappropriate sense of humor about itself or its conceit, preferring instead to explore its concept within the established backdrop of the war.

Overlord also features two breakout performances that help immerse the viewer in the material. The first is Adepo, whose strong turns in Fences (2016) and HBO’s The Leftovers earned him this starring role—a natural and sympathetic character that gradually becomes determined, if somewhat unhinged, by the vastness of the horror he witnesses. The second is by Russell (best sampled in Black Mirror or Richard Linklater’s Everybody Wants Some!!), following in his father Kurt’s footsteps by occupying the resident badass in a genre mashup. To be sure, Avery’s severe tone and commitment to the film’s world recall the deceptively simple approach of John Carpenter, who frequently made use of Kurt Russell’s charms as a leading man, which have been passed down to his son. And while cult audiences will consume Overlord with an enthusiastic response, there’s a level of craftsmanship and control behind the camera that deserves to be appreciated. Audiences looking for a good time at the movies will find themselves surprised that they’re getting something more, and it’s a higher level of quality than Nazi-zombie fare has ever received, or perhaps even deserves.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review