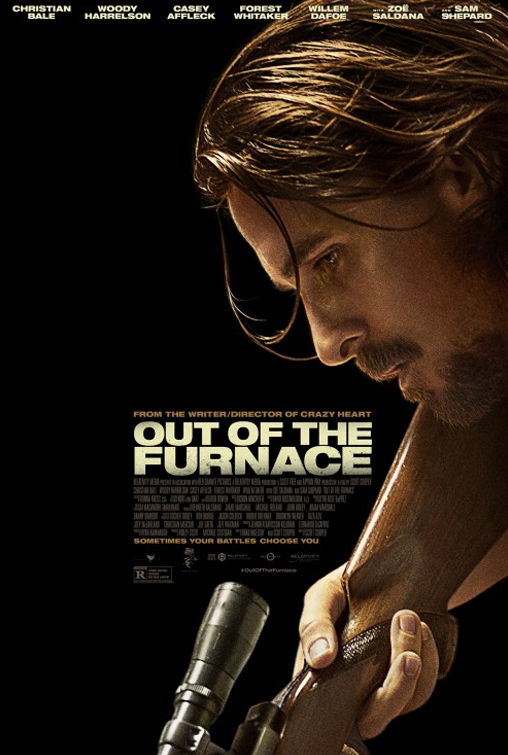

Out of the Furnace

By Brian Eggert |

Once a booming steel town, Braddock, Pennsylvania, has since become another hunk of America left deteriorated by the Rust Belt, steeped in unemployment and poverty after the aggressive rise of cheaper overseas competition. Braddock and towns like it have been the folksy locale for many a working-class drama as of late, their colors muted by gray, seemingly perpetual overcast skies and a withered atmosphere. Such a setting has given birth to sports heroes in The Fighter, and has also been the backdrop for stirring tales of human endurance in Prisoners and Unstoppable. In Out of the Furnace, the Rust Belt provides all the human despair necessary to propel the tragic figure played by Christian Bale, not to mention the impressive ensemble of rugged supporting characters around him. However, this mood piece doesn’t have enough story to support its weighty tone and backdrop.

Out of the Furnace is the second motion picture by Crazy Heart’s director Scott Cooper, who co-wrote alongside Brad Ingelsby. Both of Cooper’s films contain a downtrodden protagonist who emerges from his heavy station and surroundings to overcome them. Bale is Russell Baze, a mill worker and elder brother to Rodney (Casey Affleck). As their father slowly dies of cancer, Rodney completes tours of duty in Iraq, and Russell spends time in prison for negligence behind the wheel. After his release, Russell resumes the responsible older brother role by returning to work at the mill, which may close soon. While he was away, Russell’s girlfriend (Zoe Saldana) left him for a local cop (Forest Whitaker) and has moved on. But since getting back from Iraq the shell-shocked Rodney has been paying his debts back to a local bookie Petty (Willem Dafoe) by participating in unlawful bare-knuckle fights. When Rodney and Petty go missing after trouble with New Jersey backwoods crimelord and sociopath Harlan DeGroat (Woody Harrelson), Russell is impelled to go searching for his brother.

The narrative trajectory is very familiar, frustratingly so. There are suspicious parallels to Michael Cimino’s The Deer Hunter, with a touch of Apocalypse Now as well. Following Cimino’s film, which is also set in an industrial town, Out of the Furnace features a main character whose loved one (Rodney) is lost on a self-destructive path after his experiences fighting in a war. Like Robert De Niro’s post-Vietnam character searching for Christopher Walken’s in Russian roulette clubs in Cimino’s film, Russell is a level-headed deer hunter who must enter a dangerous underground to find his brother. Except, what Bale’s character finds is as much a product of wartime post-traumatic stress as a product of DeGroat’s Appalachian roots. The film’s unhinged villain stands over his empire of drugs and boxing, an uncontrollable force of inhumanity not unlike Col. Kurtz in Apocalypse Now. The only way to deal with such madness is to destroy it.

To complete the other half of the title’s adage, DeGroat embodies Russell’s leaping “into the fire”. In the film’s graphic first scene, Harrelson’s meanest character yet (yes, even worse than his turn in Seven Psychopaths) shoves a hot dog down the throat of his drive-in date and then beats another patron unconscious. He’s an ugly, cartoonishly evil character who admits “I got a problem with everybody” and therein colorfully announces how out of place he feels in this otherwise rustic mise-en-scène. Cooper’s cinematographer Masanobu Takayanagi (who shot another Rust Belt movie with Warrior) employs grainy and muted visuals in a handheld style, and editor David Rosenbloom cuts abruptly at times to lend a practical appeal. Outside of DeGroat, the film adopts a meditative quality to allow ample time to consider its themes of vengeance and justice. Bale and Affleck are both effective in their deeply serious roles, and Sam Shepard appears as the Baze brothers’ uncle to give the film an even greater sense of pensive, down-to-earthiness.

Cooper’s prevailing sense of gravitas wears thin once it becomes evident that Bale’s character must endure no end of suffering and loss in order to arrive at a place where he no longer has anything left to lose, and can therefore go after DeGroat without consideration of the consequences. Out of the Furnace considers a bleak outlook on economic disparity and how it shapes the lives of those affected, but the film’s methods are obvious and timeworn. The film’s message, if one exists at all, remains unclear, the forced artiness of the spare production empty. Russell seems to be propped up as a hero at the end instead of the tragic figure he appears to be, and the final scenes support a kind of down-home vigilantism that contradicts the noble human endurance represented throughout. Though Cooper and Ingelsby’s uneven script has been graced by severe character actors and another intense performance by Bale, which by themselves make Out of the Furnace worth seeing, there’s far too little substance behind them to give the film resonance.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review