Reader's Choice

Ordinary People

By Brian Eggert |

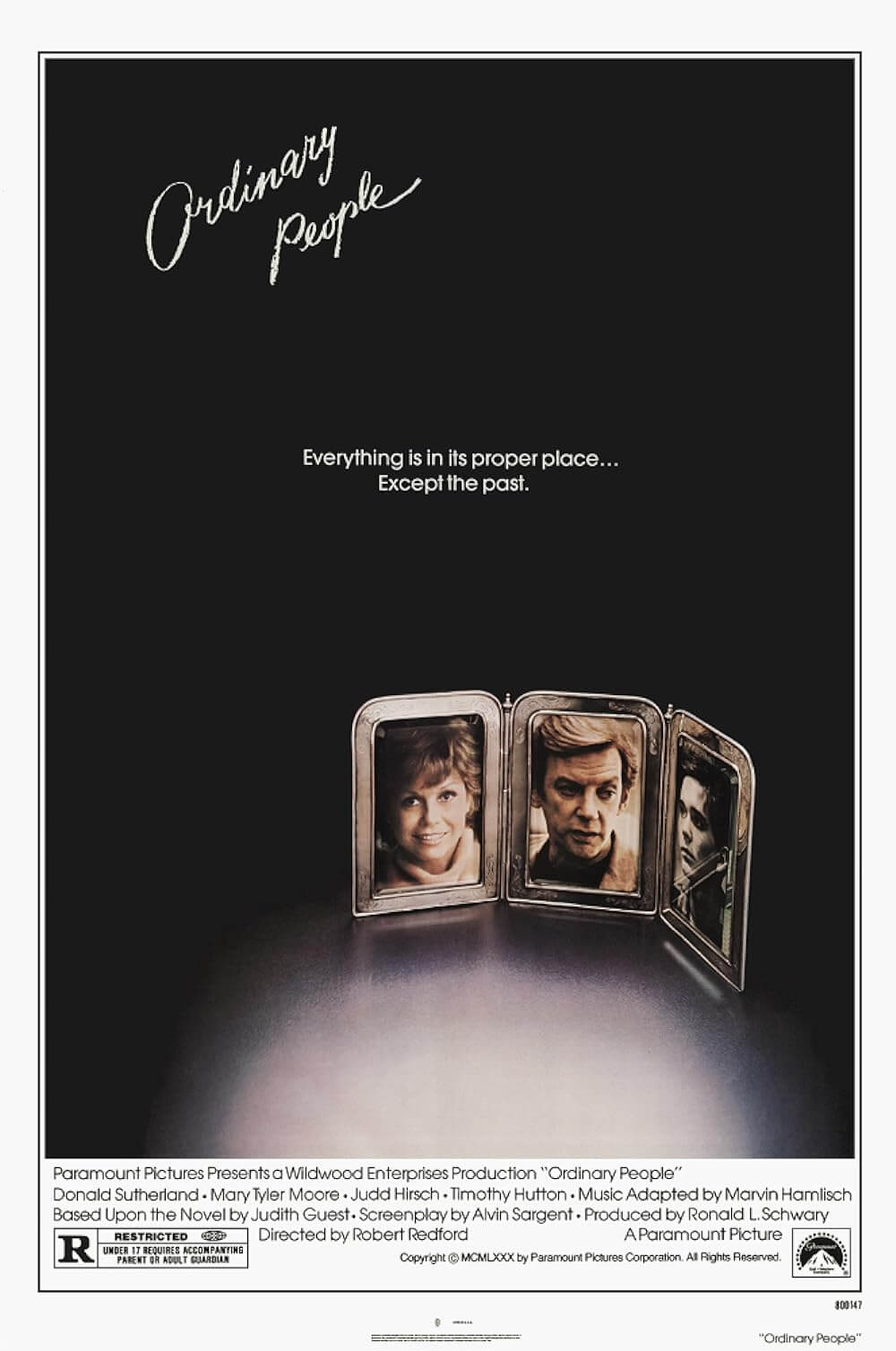

“Some films you watch, others you feel.” That’s the tagline of Ordinary People, Robert Redford’s unassuming, superbly acted drama about family members who struggle to communicate with each other. Based on the novel by Judith Guest, the film was popular among audiences who saw their own family’s hangups reflected in the Jarrett family. Many critics mistake the film as a simple production intent on emotional honesty, propelled by psychiatry, yet with a negligible mise-en-scène that has been inaptly compared to a made-for-TV movie. At first glance, the visual treatment and dramatic circumstances look familiar; since the film’s release, many have attempted to replicate its style for the small screen, and its aesthetic has become synonymous with Hallmark fare. But as Redford examines everyday problems in a manner rare for Hollywood storytelling—from crippling survivor’s guilt to the struggle of communicating openly and honestly with loved ones—his intentional restraint reveals itself in subtle but symbolic ways. If the film appears plain and straightforward, it’s because Redford has concealed his control over the production to emphasize its undeniable emotional impact. Contrary to its marketing, Ordinary People is a film that is felt so strongly because of how Redford directs the viewer’s eye.

The title calls them ordinary, but the Jarretts live in upper-middle-class comfort in the WASPy, affluent Chicago suburb of Lake Forest. The father, Calvin (Donald Sutherland), is a successful tax attorney; the mother, Beth (Mary Tyler Moore), runs the home, taking part in community organizations and fastidiously overseeing every detail of their manufactured lives. To be sure, on the surface, their house and family look immaculate. They can afford to travel every Christmas and take vacations whenever it suits them. Their son will probably go to an Ivy League school. And what about Conrad (Timothy Hutton, in his big-screen debut), whose darkened eyes hint at something not right in their suburban paradise? Conrad is the other son, number two, the one who survived. The Jarretts’ eldest, Bucky, died a year-and-a-half earlier. Conrad blames himself and attempted suicide. He spent four months in a psychiatric hospital where he went to therapy sessions and received electroshock treatments. Back at home, he feels his mother doesn’t love him. “She’ll never forgive me for getting blood all over the bathroom floor,” he tells his new therapist. Meanwhile, Conrad’s well-meaning father has love to give but doesn’t know how to communicate it.

Ordinary People takes place in a house of closed doors, literally and figuratively. It is Beth’s home, insomuch that she fusses over every detail, controlling appearances to such an extent that she prevents the family from working out their problems—or even acknowledging that problems exist—to maintain the façade. Despite Bucky’s death in a capsized boating accident, Conrad’s parents do not force therapy upon him; he seeks out help on his own, though he’s hesitant to confront his issues. Referred to Dr. Berger (Judd Hirsch), Conrad explains that he wants “control” so people will “stop worrying about me.” Conrad knows something is wrong inside him, but it’s the physical signs of his mental state, materializing in insomnia and anxiety, that draw unwanted attention—specifically from his mother. Beth assumes that Conrad is doing this to himself, that he’s choosing to behave this way and not reacting to his environment. How could his home be the problem when she keeps things so orderly? And so, to the outside world, Conrad is “great, just great,” according to his parents. But Conrad would rather be back in the hospital where people didn’t hide their feelings.

At home, Conrad and his parents talk over each other at breakfast and dinner; their communication is so incongruous that they seem to be having different conversions at the same time. Beth and Conrad try to talk outside in one scene, but the exchange diverges sharply; then Conrad barks, and Beth simply walks away. Mother and son are like two atoms that repel each other; they’re drawn together but can never connect. At the same time, husband and wife are so dependent on the same old patterns that they never stopped to consider if they still love each other. Calvin sees the problem and visits Conrad’s psychiatrist. “Naturally, I thought intelligent people can work out their own problems,” he tells Berger. But Beth will not accept responsibility for the warmth she cannot extend to Conrad, nor will she seek help or even talk about her husband’s feelings. Calvin cannot understand why, when getting ready for Bucky’s funeral, she made him change into the outfit that she wanted him to wear. Is she that obsessed with the appearance of things? Or was that her way of dealing with the problem? She responds to Calvin’s confrontation with denial, compartmentalization, and distractions such as her housework. Watch when Conrad tells his father, “I love you,” and Calvin responds, “I love you too.” Now watch when Calvin asks Beth if she loves him; her response is characteristically evasive: “I feel the way I’ve always felt about you.”

The family dynamic recalls the Starks from Rebel Without a Cause (1955)—the mother who runs the house, the trampled over father, and the son writhing because no one communicates. But where Nicholas Ray’s explosive teen melodrama had flash and style, Redford’s approach on Ordinary People is restrained but no less visually intentional, lending each scene emotional veracity. Note the increasingly dark sessions in Berger’s office that capture how Conrad’s inner light grows with each new session, until the critical moment, which takes place in the middle of the night, when Conrad re-experiences his brother’s death and projects Bucky onto Berger. Editor Jeff Kanew cuts between Berger’s office and Conrad’s memories of the stormy accident with an abruptness uncharacteristic to the film thus far. But finally, Conrad recognizes that he’s not responsible for Bucky’s death, that he was stronger than Bucky and could hold on to the capsized boat, and that he must forgive himself. Similarly, Redford’s film is less willing to blame the parents as Ray’s does. Everyone deals with trauma in their own way, and Redford understands that. And while it may seem that Beth is to blame for the Jarretts’ inability to communicate, each of them has contributed. Still, Conrad and Calvin will address their issues and work through them. Beth’s storyline is more tragic. Rather than talk about Calvin’s feelings or her lingering conflict with Conrad, she packs her bags and leaves without a word.

Ordinary People was released in 1980, a banner year for Redford that signaled his artistic legitimacy in Hollywood. Although he began acting in the 1960s, his breakout role alongside Paul Newman in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969) made him a star. He continued appearing in hits throughout the 1970s, from a romantic leading man in The Way We Were to a conman in the Best-Picture-winning The Sting, both in 1973. He also started producing his films, such as The Candidate (1972) and All the President’s Men (1976), inserting aspects of himself into his projects, including his liberal politics. Around the same time, he expressed interest in directing his own films to longtime collaborator and friend Sidney Pollack (who directed Redford a total of seven times, notably in Out of Africa and Three Days of the Condor). With Ordinary People, Redford finally made his directorial debut, earning Oscars for Best Picture and Best Director. Also in 1980, Redford launched the Sundance Institute, the foundation in Utah devoted to fostering film technology and fresh young talent as a training ground for Hollywood’s next generation of filmmakers—though, his Sundance Film Festival would become a commercialized epicenter of so-called independent film. In any case, Ordinary People and Sundance helped Redford become a brand unto himself.

Before making the film that beat out Martin Scorsese’s Raging Bull, Roman Polanski’s Tess, and David Lynch’s The Elephant Man at the Oscars, Redford had to convince everyone involved that the material was worth filming. Most major studios passed before Paramount finally agreed to distribute the picture. Screenwriter Alvin Sargent felt the characters were too simplistic, and not until Redford took him to Lake Forest parties to meet people like the Jarretts was Sargent convinced that Guest’s book held some truth. Redford’s mentor, Pollack, didn’t see the appeal of Guest’s book either. But Redford set aside the advice of those around him and proceeded anyway, delivering a production that cost just over $6 million and took home nearly $100 million in box-office receipts. Ordinary People became a critical and commercial darling while striking a familiar chord with audiences who recognized the dysfunction on display as if looking in a mirror—just as Kramer vs. Kramer had done the year before. One of the few detractors was Pauline Kael, who regularly resisted showering Redford’s career with praise, and who saw Ordinary People as a transparent attempt at self-legitimization, claiming, “Movie stars who become directors sometimes seem to choose their material as a penance for the frivolous good times they’ve given us.” Many other critics celebrated its performances and emotional truth. In The New York Times, Vincent Canby called it “so good—so full of rare feeling,” and Roger Ebert described it as “an intelligent, perceptive, and deeply moving film.”

Before making the film that beat out Martin Scorsese’s Raging Bull, Roman Polanski’s Tess, and David Lynch’s The Elephant Man at the Oscars, Redford had to convince everyone involved that the material was worth filming. Most major studios passed before Paramount finally agreed to distribute the picture. Screenwriter Alvin Sargent felt the characters were too simplistic, and not until Redford took him to Lake Forest parties to meet people like the Jarretts was Sargent convinced that Guest’s book held some truth. Redford’s mentor, Pollack, didn’t see the appeal of Guest’s book either. But Redford set aside the advice of those around him and proceeded anyway, delivering a production that cost just over $6 million and took home nearly $100 million in box-office receipts. Ordinary People became a critical and commercial darling while striking a familiar chord with audiences who recognized the dysfunction on display as if looking in a mirror—just as Kramer vs. Kramer had done the year before. One of the few detractors was Pauline Kael, who regularly resisted showering Redford’s career with praise, and who saw Ordinary People as a transparent attempt at self-legitimization, claiming, “Movie stars who become directors sometimes seem to choose their material as a penance for the frivolous good times they’ve given us.” Many other critics celebrated its performances and emotional truth. In The New York Times, Vincent Canby called it “so good—so full of rare feeling,” and Roger Ebert described it as “an intelligent, perceptive, and deeply moving film.”

Ordinary People is a film calibrated around great performances given by a well-chosen cast. Though Redford couldn’t convince his first choice for Calvin, Gene Hackman, to accept the role, he went with Donald Sutherland, whom he initially interviewed to play Berger. Hirsch agreed to play Berger only if his scenes could be filmed to accommodate his schedule on television’s Taxi, and so Redford shot the isolated psychiatric scenes in just a few days. For Conrad, Redford went on a wide-ranging search for talent before settling on the 19-year-old Hutton, who had just lost his father, actor James Hutton, to cancer a few months earlier. Doubtless, Hutton used the pain of this recent loss in the performance, which earned him the Oscar for Best Supporting Actor. The same is true of Moore, whose son died in an accidental shooting death and whose sister committed suicide. On and off screen, Moore, who was also in a declining marriage and grappling with alcoholism, would mask her inner pain with her outward appearance—a smile synonymous with her comic persona from The Dick Van Dyke Show in the 1960s and her own sitcom in the 1970s. Redford, too, had just started to grapple with his failing marriage and acknowledge his troubled relationship with his own father. Channeling these off-screen stimuli, Redford worked with his actors to craft performances free of affectation and overflowing with human dimension.

The outward simplicity of Redford’s direction is staggering, yet his choices remain elegant and informed. The title sequence features no score, just white letters on a black background. Gradually, the black lightens into a blue autumn sky, indicating through color the trajectory of the drama, from a dark void of silence into a realm of understanding. The film features Johann Pachelbel’s Canon in the choir scenes and on the soundtrack—and how fitting that it’s a piece played ubiquitously at weddings and funerals, echoing the film’s equal measures of emotional progress and cessation. Appropriately, the setting begins in fall and climaxes around Christmas, opening with several picturesque shots of orange leaves falling from trees. An early scene also shows Beth giving candied apples to local trick-or-treaters on Halloween. “That is the scariest ghost I’ve ever seen,” she says, humoring the children. What could be more appropriate since Bucky’s memory haunts the Jarrett home? Indeed, Redford employs classical dramatic symbolism with autumn and winter—the former, a time of ghosts and goblins, and a signifier of decline; the latter traditionally indicates death and remoteness. Ordinary People simply wouldn’t work in spring or summer unless the contrast were intended as irony.

Redford’s visual schema is almost distractingly invisible; it’s rare to notice a camera movement or angle in the film. Redford told Cinéaste, “What I had in mind with that film was to suggest peeking into someone’s life, looking through a keyhole into someone’s life.” And when one looks through a keyhole, the visual choices prove limited. Cinematographer John Bailey—who shot expressively for Paul Schrader’s most pronounced ‘80s efforts of American Gigolo (1980), Cat People (1982), and Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters (1985)—exercises such discipline that his approach might be mistaken as generic. But as the film’s tagline indicates, its presentation allows the viewer to feel their way through the proceedings, never distracted by undue form. And though the material comes from a novel, Redford shoots the drama as though he’s making a stage adaptation with limited locations. His work as director seems limited to shaping performances. For this reason, Pollack tried to talk Redford out of making Ordinary People as his first feature in favor of something more visual since he had no experience directing actors. But Redford’s modest visuals show his careful calibration of each scene, allowing his characters to live and breathe, while never overemphasizing the underlying symbolism. After Beth drops a plate, she regards the two halves and says, “I think this can be saved. It’s a nice clean break.” Redford does not underline the moment; he inserts it into casual conversation, though it encapsulates Beth’s approach to her family’s loss.

Redford’s visual schema is almost distractingly invisible; it’s rare to notice a camera movement or angle in the film. Redford told Cinéaste, “What I had in mind with that film was to suggest peeking into someone’s life, looking through a keyhole into someone’s life.” And when one looks through a keyhole, the visual choices prove limited. Cinematographer John Bailey—who shot expressively for Paul Schrader’s most pronounced ‘80s efforts of American Gigolo (1980), Cat People (1982), and Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters (1985)—exercises such discipline that his approach might be mistaken as generic. But as the film’s tagline indicates, its presentation allows the viewer to feel their way through the proceedings, never distracted by undue form. And though the material comes from a novel, Redford shoots the drama as though he’s making a stage adaptation with limited locations. His work as director seems limited to shaping performances. For this reason, Pollack tried to talk Redford out of making Ordinary People as his first feature in favor of something more visual since he had no experience directing actors. But Redford’s modest visuals show his careful calibration of each scene, allowing his characters to live and breathe, while never overemphasizing the underlying symbolism. After Beth drops a plate, she regards the two halves and says, “I think this can be saved. It’s a nice clean break.” Redford does not underline the moment; he inserts it into casual conversation, though it encapsulates Beth’s approach to her family’s loss.

If the title is any indication, Ordinary People presents an alternative to Hollywood cinema up to 1980 by dealing with everyday family dynamics without over accentuating them for cinematic ends. Other films present fantasies and heightened drama in an entertaining way, often dealing with extraordinary characters under equally impossible circumstances. Redford deals with common family problems in a way that diverges from the usual methods of Hollywood drama. Ordinary People remains so powerful because of how Redford selflessly allows it to confront how family members express, or don’t, their love, and because the Jarretts, regardless of their privilege, seem so familiar. The degree to which people open or close themselves off to love shapes the dramatic foundation of the film. When watched on those terms, its effect is overwhelming, and his direction is masterfully self-possessed. His characters are human, and his film’s solution is rational: when families talk honestly, either with each other or through a professional, their problems can be solved or healed. It’s a testament to the film’s sobering emotional maturity that it recognizes how a seemingly simple solution proves achingly complex for the average family.

(Editor’s Note: This review was commissioned on Patreon. Thanks for your support, Brian R.!)

Bibliography:

Callan, Michael Feeney. Robert Redford: The Biography. Knopf Doubleday, 2011.

Cosandaey, Mikelle, and Robert Redford. “Combining Entertainment and Education: An Interview with Robert Redford.” Cinéaste, vol. 16, no. 1/2, 1987, pp. 8–12. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41687508. Accessed 1 May 2021.

Eberwein, Robert T. “The Structure of ‘Ordinary People.’” Film Quarterly, vol. 11, no. 1, 1983, pp. 9–15. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/43797288. Accessed 1 May 2021.

Thomson, David. “Ordinary Bob: Can Robert Redford Ever Explode?” Film Comment, vol. 24, no. 1, 1988, pp. 32–35. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/43453207. Accessed 1 May 2021.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review