Oppenheimer

By Brian Eggert |

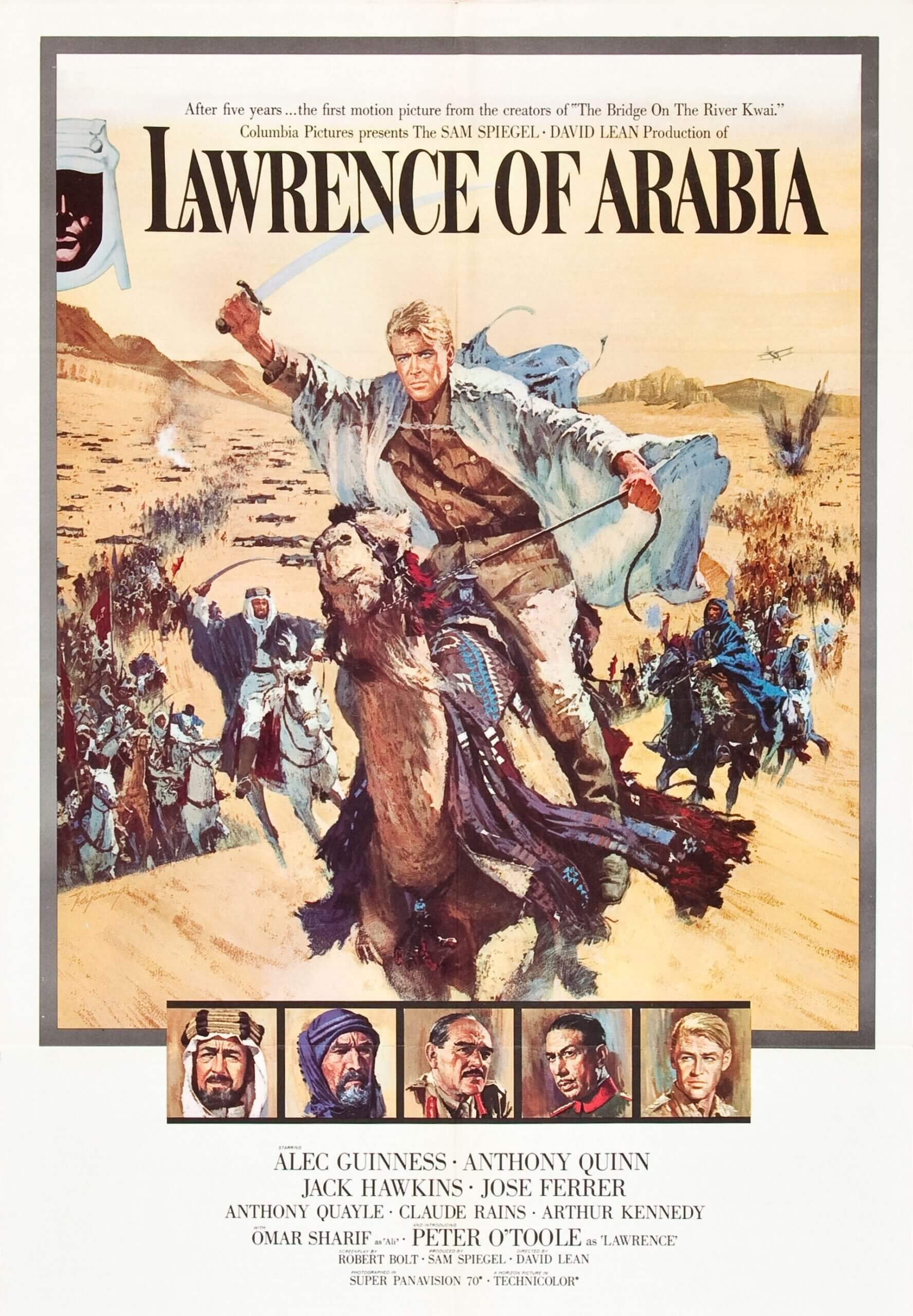

Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer is an epic-sized biography about a complex historical figure. Unlike anything the director has made, the film doesn’t rely on mind-bending scenarios or stunning special effects to astound his audience into submission. His production’s greatest effect is the central performance by longtime collaborator Cillian Murphy, who delivers an articulate and immersive turn as J. Robert Oppenheimer, the so-called father of the atomic bomb. That designation never pleased Oppenheimer, who felt a magnetic pull toward the discovery and use of nuclear weaponry, both as a brilliant quantum physicist and a Jewish man compelled to end World War II. He lamented that his name was associated with a weapon that left hundreds of thousands dead from the initial detonation to the lasting effects of radiation and cancer. And he deplored using the bomb, even though he believed humanity needed this example to stop all future wars. Nolan’s take on the character has all the flaws, disharmonies, and intensity of David Lean’s titular character from Lawrence of Arabia (1962), except Oppenheimer doesn’t quite measure up to that film in terms of scope. Marked by political maneuvering and dialogue-heavy writing, Nolan’s script, for once, doesn’t over-explain what’s happening and why. He delivers an equivocal film about a paradoxical character, and he refuses to answer every question about him.

After Warner Bros. botched the theatrical distribution of Nolan’s last, rather underwhelming feature, Tenet (2020), the director left his longtime studio home base for Universal to develop Oppenheimer. Working on a smaller budget than he’s accustomed to—a mere $100 million—Nolan tackles his most human-centric film yet. Setting aside the usual temporal and structural gamesmanship that often accompanies and defines his work, from Memento (2000) to Inception (2010) to Dunkirk (2017), his treatment of Oppenheimer is no less cerebral. Instead of piecing together a narrative puzzle, Nolan and editor Jennifer Lame paint a nonlinear portrait from fragmentary information, applying color from scenes spanning a lifetime and organizing them into a somewhat impressionistic whole. But the film is not without a method. Nolan introduces a secret and preserves it for much of the three-hour runtime, offering a final Rosebud-like revelation about what Oppenheimer and Albert Einstein (Tom Conti) discussed among themselves at a crucial meeting—much to the annoyance of Oppenheimer’s later nemesis, Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey, Jr.), chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission, so much so that Strauss sets the film’s political conflict into motion based on a paranoid assumption.

Nolan’s script draws from the 2005 biography by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherman, American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer. Although the narrative structure defies linearity, the proceedings gradually take shape and orbit around two official hearings: The most immediate to the protagonist places Oppenheimer in the throes of a panel reviewing his security clearance in the years after World War II, requiring him to recollect and remark on many of his life choices and vague associations with the Communist Party. The other involves a hearing to assess Strauss’ application to President Dwight Eisenhower’s cabinet. Shot in black-and-white, Nolan insists the latter thread provides an objective, factual account, whereas the color scenes belong to Oppenheimer’s subjectivity. The narrative devices, combined with the switches from monochrome to color, recall Oliver Stone’s work in the 1990s, with particular allusion to 1995’s Nixon—both Stone’s film and Nolan’s film are about a historically divisive character rapt by personal failings and landmark victories, conveyed with a blend of subjective evidence and objective truths. Given the film’s use of official inquiries, it’s perhaps strange, then, that Nolan has boasted about shooting the movie in IMAX format and offering a few 70mm nationwide screenings.

When properly projected, a 70mm print looks better than the clearest digital projector, offering more detail, brighter colors, and immersive scale. However, celluloid projection is a dying art, requiring the projectionist’s skill and attention. Evidenced by the press screening of Oppenheimer in the Twin Cities, the projectionist couldn’t be bothered to eliminate projector wobble and couldn’t tell that the image was out of focus ever-so-slightly. I suspected as much throughout, asking myself whether I needed a new prescription for my astigmatism or if something was off about the projected image. Yet, when the title finally appeared against a black background at the end, revealing soft edges on the lettering, the problem was unmistakable. This does not reflect poorly on the film, of course; it’s just an observation that, despite Nolan attempting to deliver the most premium cinematic experience for his latest, his efforts may be undone because few projectionists today know how to handle celluloid projectors. Nolan’s idol, Stanley Kubrick, known for his letters to projectionists and obsessively overseeing the quality of his prints, would have fumed over such an exhibition. Hopefully, your viewing experience is better. But I digress.

When properly projected, a 70mm print looks better than the clearest digital projector, offering more detail, brighter colors, and immersive scale. However, celluloid projection is a dying art, requiring the projectionist’s skill and attention. Evidenced by the press screening of Oppenheimer in the Twin Cities, the projectionist couldn’t be bothered to eliminate projector wobble and couldn’t tell that the image was out of focus ever-so-slightly. I suspected as much throughout, asking myself whether I needed a new prescription for my astigmatism or if something was off about the projected image. Yet, when the title finally appeared against a black background at the end, revealing soft edges on the lettering, the problem was unmistakable. This does not reflect poorly on the film, of course; it’s just an observation that, despite Nolan attempting to deliver the most premium cinematic experience for his latest, his efforts may be undone because few projectionists today know how to handle celluloid projectors. Nolan’s idol, Stanley Kubrick, known for his letters to projectionists and obsessively overseeing the quality of his prints, would have fumed over such an exhibition. Hopefully, your viewing experience is better. But I digress.

In a move reminiscent of Quentin Tarantino’s The Hateful Eight (2015), another film projected on 70mm, much of Nolan’s film takes place in enclosed spaces—classrooms, Los Alamos labs, cramped conference rooms, hearing rooms teeming with people. These would seem an incongruous choice for a format often associated with grand cinematic epics, but the effect treats Oppenheimer’s face as a vast panorama of detail and flinty emotions. The exception is the scopic Trinity Test sequence, where Nolan and cinematographer Hoyte van Hoytema zoom over the New Mexico landscape to find a skeletal tower from which the test bomb will drop. Nolan builds to this moment for the first two hours of Oppenheimer, implanting dread about the possibility that the test may set off a chain reaction that could ignite the atmosphere. But like Oppenheimer, General Groves (Matt Damon), who oversees the Manhattan Project in Los Alamos for the US military, insists they take a risk on what fellow physicist Edward Teller (Benny Safdie) believes is a minor probability. Building to this sequence, and beyond it, Nolan and Lame’s editing feels propulsive, often leaping to the next image in the middle of a line in a manner that sometimes feels disruptive to the visual rhythm, though the winding, lyrical music by Ludwig Göransson holds the film together.

Although most will enter Oppenheimer thinking the climactic moment arrives with the first successful test of an atomic bomb, Nolan has another hour to investigate his characters, their political and personal drives, and question the conventional justifications for dropping the bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki—supported by Strauss, who suggests that Japan would have never surrendered. Perhaps because Oppenheimer wants to maintain control over his invention, perhaps because he wants to preserve his power, he doesn’t speak up too loudly against using the bomb or developing a postwar arsenal to protect the US from the Soviet Union. A scene where he meekly appeals to Truman (Gary Oldman) about the dangers of an arms race earns him nothing but mockery from the brash POTUS. But then, Nolan’s film takes place in a world before digital video could give you real-time access to war footage. Oppenheimer and the officials who decide to bomb Japan (in a cynical scene that finds James Remar’s Henry Stimson resolving not to bomb his favorite vacation spot, Kyoto) could do so without having to witness the destruction first-hand. Still, Oppenheimer imagines Americans with singed skin peeling off their faces, their bodies left in ashen husks, like the remains of those dead in Pompeii. However, the politicians show no remorse or humanity, and even if they could see the horrific effects of the bomb, Nolan leaves the impression that their narrow-minded urge to protect their power would no doubt overcome any pesky humanist reservations.

Even though much of Oppenheimer entails the life-and-death stakes surrounding the bomb, this is a character study first and foremost, so Nolan delves into Oppenheimer’s personal relationships with colleagues and lovers. Nolan doesn’t have much interest in the women in Oppenheimer’s life (and writing women has never been his strong suit), giving them little dimension apart from their role in the protagonist’s life, which, in turn, reflects the film’s subjective perspective and thus Oppenheimer’s view of women—secondary to science. Florence Pugh has a small but impassioned role as his mistress, Jean Tatlock, a character reduced to a fiery communist sexpot. Emily Blunt serves better as his wife, Kitty, who drinks to escape her stifling domestic drudgery. Kitty’s potential is merely glimpsed in a late scene when she verbally spars with a lawyer (Jason Clarke), who attempts to discredit her husband, though she has every reason not to defend his character. Nolan doesn’t look too deeply into their relationship except to show Kitty’s tough skin emerge whenever her husband is vulnerable. Elsewhere, Nolan populates his cast with a distracting number of familiar faces in minor roles, far too many to list out, though Kenneth Branagh, Josh Hartnett, Matthew Modine, and David Dastmalchian leave an impression.

Even though much of Oppenheimer entails the life-and-death stakes surrounding the bomb, this is a character study first and foremost, so Nolan delves into Oppenheimer’s personal relationships with colleagues and lovers. Nolan doesn’t have much interest in the women in Oppenheimer’s life (and writing women has never been his strong suit), giving them little dimension apart from their role in the protagonist’s life, which, in turn, reflects the film’s subjective perspective and thus Oppenheimer’s view of women—secondary to science. Florence Pugh has a small but impassioned role as his mistress, Jean Tatlock, a character reduced to a fiery communist sexpot. Emily Blunt serves better as his wife, Kitty, who drinks to escape her stifling domestic drudgery. Kitty’s potential is merely glimpsed in a late scene when she verbally spars with a lawyer (Jason Clarke), who attempts to discredit her husband, though she has every reason not to defend his character. Nolan doesn’t look too deeply into their relationship except to show Kitty’s tough skin emerge whenever her husband is vulnerable. Elsewhere, Nolan populates his cast with a distracting number of familiar faces in minor roles, far too many to list out, though Kenneth Branagh, Josh Hartnett, Matthew Modine, and David Dastmalchian leave an impression.

Murphy’s performance is marvelous, comparable to Peter O’Toole’s in the aforementioned Lawrence of Arabia. An ever-magnetic presence since his breakout in 28 Days Later (2002), the actor replicates Oppenheimer’s severe, almost fervent eyes that seem to bulge with feverish brilliance. Like T.E. Lawrence, Oppenheimer is driven toward actions he intellectually abhors, and he’s quite naive to the political consequences, but he is compelled by his hubris and obsessive need to know if the fractured images of atoms firing in his mind can be achieved. Another similarity to Lawrence is that Oppenheimer dabbles in identities, shifting from the role of a physicist to a politician freely, just as Lawrence alternated between a British soldier and an Arabian desert warrior, fully inhabiting each role. Oppenheimer even tries on communism for a time, leading to many questions about his loyalties during the Red Scare. Much of the hearing into his security clearance attempts to unpack why Oppenheimer associated with left-wing causes or had communist friends, and the answers remain unclear if circumstantial and too complicated to distill. “Nobody knows what you believe,” Teller observes somewhat pointedly. “Do you?” Oppenheimer is unquestionably Nolan’s most intricate character to date, and Murphy brings him to life in a three-dimensional performance that will be what the film is remembered for.

Oppenheimer might drag in the final act, but the structure will reward another viewing, as most Nolan films do. Nolan’s general perspective won’t challenge the audience, as he seems sympathetic to scientists like Oppenheimer, who has the greater good in mind yet remains a thorny individual, and he admonishes politicians like Strauss, who cannot see beyond their self-obsession and personal ambition. Fortunately, Nolan never reduces his film to political message-making, as many unsubtle films today do in our politically demarcated culture. What’s curious is that the film doesn’t play like summer blockbuster material, no matter how much Nolan wants to convince us of the story’s epicness. Rather, it’s a probing drama about a multifaceted individual, anchored by a stunning central performance. So the writer-director’s usual emotional distance aligns well with his subject, a man whose genius and perspective could not be summarized into a simple biographical portrait. Oppenheimer’s entangled identity provides a fascinating topic, and Nolan’s film focuses on the individual more than any other or the historical surroundings, leaving all else except Oppenheimer to feel secondary and occasionally underserviced. But like the best films about real-life figures, Oppenheimer is about the main character’s mass of psychological contradictions, challenging the audience to empathize and understand him without telling us how.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review