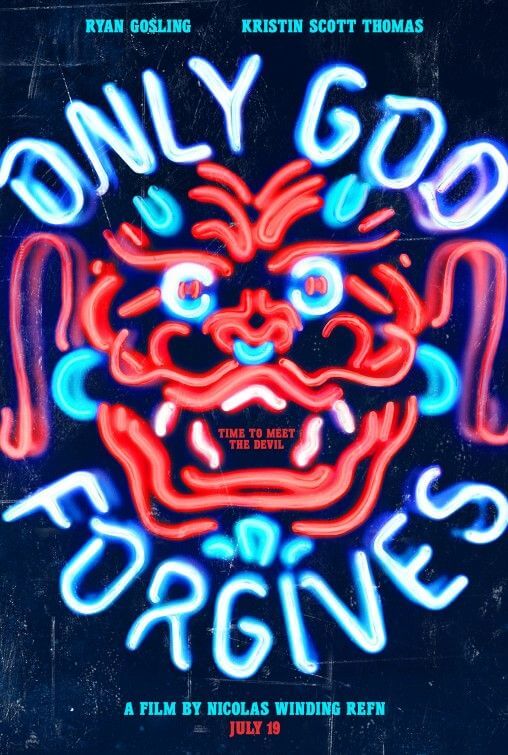

Only God Forgives

By Brian Eggert |

Nicholas Winding Refn’s Only God Forgives received boos when it premiered at this year’s Cannes Film Festival, this just two years after the Danish filmmaker won the Best Director prize for his breakthrough Drive. Winding Refn reteams with that film’s star Ryan Gosling for another spare mood piece layered with garish violence and a master’s control of his technical craft. But their second collaboration has none of the dramatic tension or emotional payoff of their first. Only God Forgives is an empty, undoubtedly pretentious, possibly pointless exercise in style. Certainly, some abstract meaning could be applied to everything onscreen, but watching the film, I had no earthly idea of what Winding Refn was trying to convey.

Gosling stars as Julian, an American drug kingpin living in Bangkok, where the film was shot. As a front for his illegal activities, Julian runs a Muay Thai kickboxing arena along with his two brothers, the unhinged Billy (Tom Burke) and the uninteresting Byron (Byron Gibson). When Billy rapes and murders a 16-year-old prostitute, Thai detective Chang (Vithaya Pansringarm) arrives on the scene and doles out his brand of medieval justice—he locks Billy in a room with the girl’s father, who proceeds to beat Billy to death. Chang’s biblical morals don’t stop there; after the father’s done, Chang chops off the father’s arm for forcing his daughter into a life of prostitution. Beset by waking dreams of Chang chopping his hands off, Julian deals with grief by watching his favorite whore, Mai (Yayaying Rhatha Phongam), masturbate in front of him.

Enter Crystal (Kristin Scott Thomas), Julian’s acid-tongued mother who arrives in Bangkok to ensure her son’s death is avenged. Her character is somewhere between Dennis Hopper in Blue Velvet and Diane Ladd in Wild at Heart; she has an oedipal relationship with her son. Julian sits by devotedly as his mother—who’s decked out in cheap clothes, thick eye makeup, and long blonde locks—derides him with no end of vile insults and meanness. She wants Billy’s killer dead, even though Julian defends the killing by explaining what his brother did. “I’m sure he had his reasons,” she says, unconcerned that her dead son was a rapist and murderer. Meanwhile, when Chang isn’t at the karaoke club singing like an angel, he’s out delivering holy justice with his sword. No doubt we’re meant to see Chang as some kind of God-like figure to whom Julian eventually answers for his past sins.

The violence in the film is brutal, gory, and excessive, and perhaps modeled after the director’s affection for grindhouse midnight movies, according to interviewer Simon Abrams. Not only does Chang remove a number of limbs throughout the film, but he also tortures one man in a scene that outdoes even the tortures in Oldboy. Later, Chang accepts Julian’s challenge to a fight in the kickboxing arena, where he pummels his opponent to a bloody pulp. Winding Refn has made bold statements to Abrams that “art is an act of violence” and admits his influence from Alejandro Jodorowsky (El Topo), whose own surreal and arty brooding inspired the director enough to earn Jodorowsky a dedication at the end of the film. But the violence in Only God Forgives isn’t diverting or even particularly confronting. Like almost every aspect of the film, from the acting to Winding Refn’s long, pensive shots, the violence sits onscreen like a slab of meat waiting to be seasoned and seared on the grill.

Borrowing from the likes of Stanley Kubrick and David Lynch, the director and his cinematographer Larry Smith (who collaborated with Kubrick more than once) work in slow, meditative shots of long hallways and stationary, blank-stare characters. Julian wanders around the extensive passages of a nightclub, drifting in an out-of-the-shadows-like Bill Pullman in Lost Highway, while the nightclub itself looks like something out of a dream had by Twin Peaks’ Special Agent Dale Cooper, except illuminated by neon and dramatic backlighting. Winding Refn presents his own Kubrickian or Lynchian quality of despondency and silence, but without the grand metaphors that bring meaning to the careful compositions of a given scene. To be sure, the film features some gorgeous looking shots of a static Gosling standing statuesque in a room of bright reds or blues, but to what purpose?

Everything onscreen feels inconsequential and in service of mood or style. Aside from Scott Thomas, whose performance is magnificently over-the-top, the actors and storyline have almost no humanity to them, serving only the film’s vague metaphor about punishment. Gosling’s contemplative, almost robotic movements have none of the under-the-surface tensions or subtleties he brought in Drive, in part because the mysteries of this underdeveloped character have almost no consequence on the viewer. Maybe this is the point, and Only God Forgives is an arthouse parable for sin and the neverending, futile search for forgiveness of oneself. Or maybe the director thought he could get away with assembling a bunch of familiar, heavy styles and piece them together in a way that would emulate his betters. Except the outcome has none of the mastery, purpose, or grand design of a Kubrick, Lynch, or Jodorowsky. It has only an empty, pretentious embrace of mood under the pretext of arthouse cinema.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review