One Life

By Brian Eggert |

In an unfortunate oversimplification, the press usually calls Nicholas Winton the “British Schindler.” A London stockbroker with German-Jewish heritage, Winton was made famous in the late 1980s after a story broke about how he helped save 669 children from the Nazis in Czechoslovakia, most of them Jewish, through the Kindertransport project. Along with several others, including his mother, Winton raised money, fought through government bureaucracy to acquire visas, and arranged foster families for the displaced children. But unlike Oskar Schindler, Winton wasn’t working with the Nazis as a war profiteer at the time, nor was he as complex a subject for a narrative treatment. Regardless, his story, as told in One Life, is deeply moving and heartrending. Screenwriters Nick Drake and Lucinda Coxon adapt the 2014 book about Winton, If It’s Not Impossible… The Life of Sir Nicholas Winton, written by his daughter Barbara, into a conventional but inspiring film, capably directed by James Hawes. While the subject matter may be familiar in some respects, the topic of displaced children, separated from their families, facing either death or a narrow survival, never loses its potency.

Anthony Hopkins stars as Winton in scenes set in 1987, which find him in retirement, his wife Grete (Lena Olin) insisting that he clean up his cluttered office. Amid boxes of old paperwork is a briefcase containing a scrapbook with photographs, letters, newspaper clippings, and documents that detail the history of his effort to save as many Czechoslovakian children as he could from the Nazis. Johnny Flynn plays the younger version of Winton in flashbacks to 1938, when it was England, France, and Italy’s policy to give Adolf Hitler the Sudetenland, the Czech province that shared a border with Germany, in hopes of avoiding an all-out war. Thousands fled the area, headed toward Prague, where Winton and his compatriots travel to provide humanitarian aid. Alongside three others (Romola Garai, Alex Sharp, Juliana Moska), Winton sees the displaced families starving and freezing in refugee camps first hand. Winton feels he must act, so he calls home to his mother (Helena Bonham Carter) to finagle the British government and media into action, while his team organizes from the Prague end.

The operation begins small, with 20 of the most dire cases sent along as proof of concept. Eventually, Winton and company arrange for nine transfers with increasingly more children, traveling by train across Europe, including Germany, to safety in England. But before the last train can depart, the Nazis put a stop to their efforts. Back in 1987, Winton doesn’t consider himself a savior or seem satisfied with what he accomplished; instead, he’s haunted by the knowledge that 15,000 children in Czechoslovakia alone went into concentration camps—especially the 253 children on the last train from Pague the Nazis stopped. How much more could he and others have done? Photos in his scrapbook of children, many of whom he interacted with and personally photographed, also remain seared in his memory.

One Life unfolds rather predictably, with Hawes and cinematographer Zac Nicholson delivering an assured, straightforward presentation. Editor Lucia Zucchetti alternates between 1938 and 1987 to capture how the events remain fresh in Winton’s mind. Though Hopkins is the draw, Flynn, from Emma (2020) and The Outfit (2022), delivers another worthy performance, making for a convincing younger version of his elder counterpart. Also in the supporting cast, Jonathan Pryce appears for a single scene opposite Hopkins, and the two exude a casual familiarity that demonstrates how much a skilled actor can elevate a simple scene. Bonham Carter doesn’t have much to do besides make phone calls and take meetings, but Garai’s urgent and passionate role on the front lines is the film’s most harrowing. Then again, much of the dramatic wallop comes from seeing so many anonymous children separated from their parents, who they’re never likely to see again, for a train ride into an unknown future.

One Life unfolds rather predictably, with Hawes and cinematographer Zac Nicholson delivering an assured, straightforward presentation. Editor Lucia Zucchetti alternates between 1938 and 1987 to capture how the events remain fresh in Winton’s mind. Though Hopkins is the draw, Flynn, from Emma (2020) and The Outfit (2022), delivers another worthy performance, making for a convincing younger version of his elder counterpart. Also in the supporting cast, Jonathan Pryce appears for a single scene opposite Hopkins, and the two exude a casual familiarity that demonstrates how much a skilled actor can elevate a simple scene. Bonham Carter doesn’t have much to do besides make phone calls and take meetings, but Garai’s urgent and passionate role on the front lines is the film’s most harrowing. Then again, much of the dramatic wallop comes from seeing so many anonymous children separated from their parents, who they’re never likely to see again, for a train ride into an unknown future.

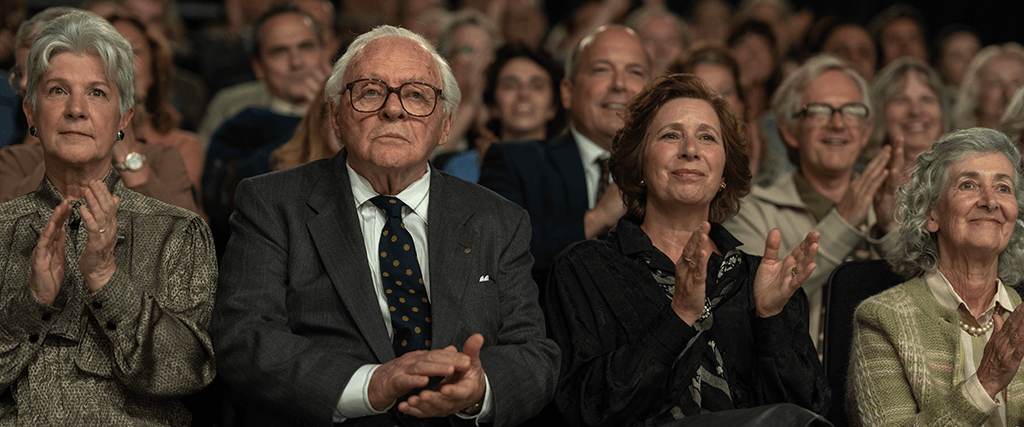

Hopkins’ portrait of Winton may seem stoic and contained at first, but his eventual breakdown when coming face-to-face with someone he saved so many years later recalls Tom Hanks’ emotional outpouring at the end of Captain Phillips (2013), when all those pent-up feelings explode outward in a profoundly moving scene. It’s difficult to imagine anyone not brought to tears by Hopkins’ performance or this moment. However, somewhat frustrating is the last section, where talk show host Esther Rantzen (Samantha Spiro) invites Winton to the audience of her popular program That’s Life! to spring a gotcha surprise on him—twice—by revealing that some of the children he saved are seated around him. The moment is a tasteless way to bring attention to Winton’s example, but at least it helped spread the word about the story across the UK and abroad. Afterward, more credible newspapers and publications relayed the tale of Czech children without having to resort to lowbrow, ratings-hungry tactics.

There’s a tendency among some critics to dismiss movies about Nazi aggression and the Holocaust because they tell a familiar story. How many films have covered this subject, and how many more will there be? However, according to recent national surveys of American Millennials and Generation Z, over 60 percent of these generations do not know basic facts about the Holocaust, when it happened, who perpetrated it, where it occurred, and how many died. Alas, we cannot assume that everyone knows what the Nazis did and how over six million Jews died in concentration camps. More than 30 states in the US don’t require education about the Holocaust, leaving people unaware and unable to recognize how and when history repeats itself. Movies like One Life or last year’s The Zone of Interest help start that conversation, but, no matter how many features address the subject, it will never be enough.

Help Keep Deep Focus Review Independent

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review