One Cut of the Dead

By Brian Eggert |

Orson Welles described a director as someone who “presides over accidents.” Having attempted a few independent short films that I’d prefer no one ever see, the truth of this sentiment resonates. Equipment breaks down or malfunctions. Actors prove unreliable. Personalities clash under pressure. Budget and time factors create tension. Nothing seems to go as planned. But then you read about filmmakers such as Welles, Renoir, and Bergman, apparent masters of their craft. You read how they rarely made a picture that turned out as they intended. Filmmakers must be extraordinary optimists, capable of focusing on what works about the end result—or that the project was completed at all—as opposed to dwelling on the many hundreds of compromises along the way. With an outrageous meta conceit, One Cut of the Dead captures the independent filmmaking experience in all its horrible but ecstatic glory. After all, what could be worse (or more artistically motivating) than zombies invading your film set?

Before diving further into the film, I should warn that assessing One Cut of the Dead with any depth will inherently reveal more than some viewers would care to know. If you haven’t seen the film and intend to, revisit this review afterward, knowing it has earned my hearty recommendation for both zombie comedy fans and those interested in films about filmmaking (a subgenre beloved by cinephiles). It’s the sort of film that will work regardless of how much you know about it, but a few major surprises along the way completely alter the structure and even the genre of the film. That’s the clever part of writer-director Shin’ichirô Ueda’s independently made, ultra-low-budget breakthrough. With a price tag of just $25,000, the film debuted in Japan in two theaters, after which it proceeded to become a modest worldwide phenomenon, earning more than $30 million since 2017. It has just arrived in the U.S. in a few isolated theatrical screenings, followed by a release on the horror-themed streaming service, Shudder.

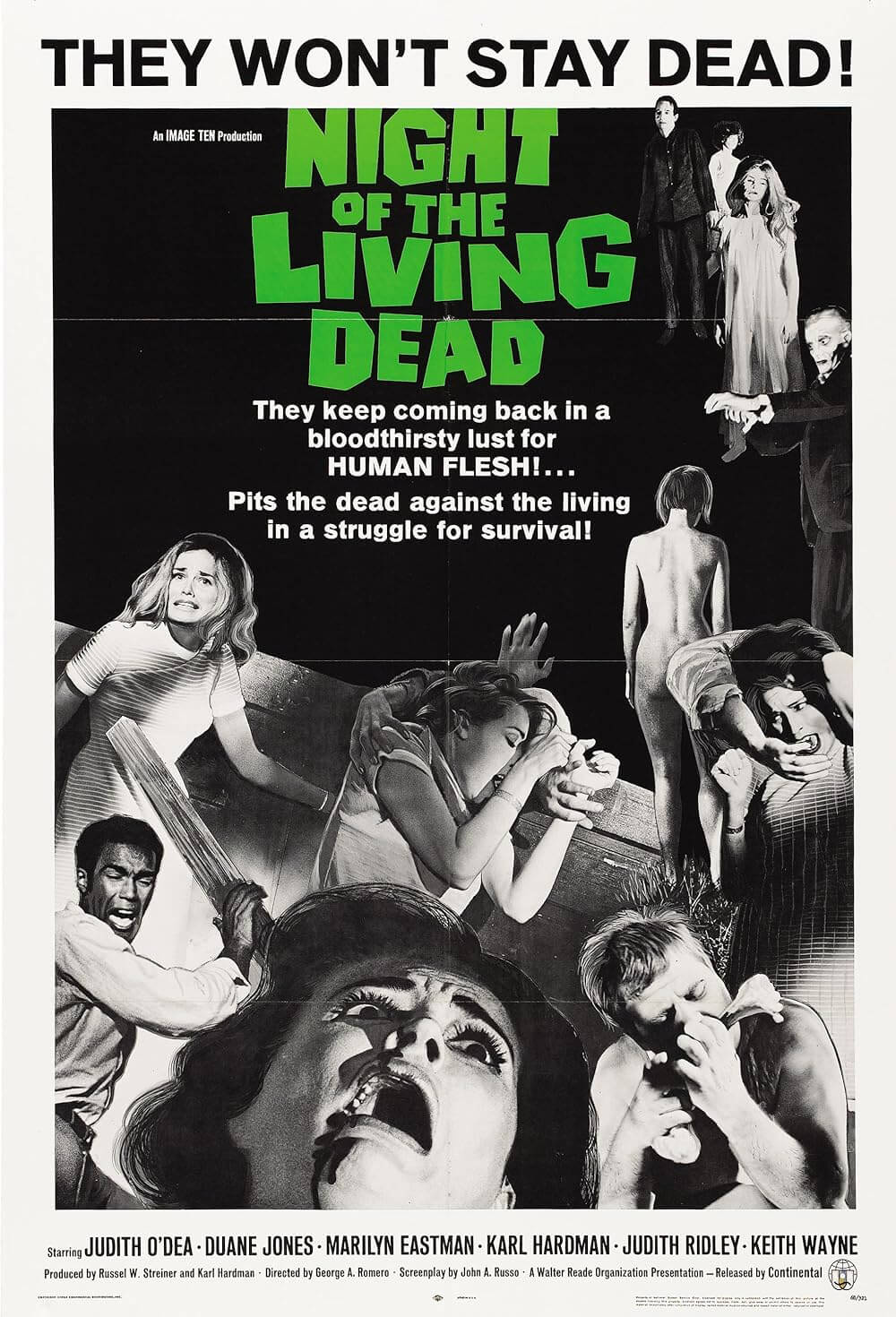

The self-reflective premise entails the skeleton crew of a low-budget production shooting a zombie movie guerilla-style in an abandoned water filtration plant (formerly a military research facility). A young actor (Kazuaki Nagaya) appears as a flesh-eater, his skin painted with primary-blue paint straight out of Dawn of the Dead (1978). Arms outstretched, he slogs after his girlfriend (Yuzuki Akiyama), still among the living, but she can’t quite nail the look of fear demanded by the film-within-a-film’s director, Higurashi (Takayuki Hamatsu). After dozens of takes, the production takes a brief pause only to be invaded by actual zombies. Though his cast and crew are terrified, Higurashi couldn’t be happier. ”No fiction. No lies. This is reality!” he cheers. It’s not that original of an idea, of course, as George A. Romero already riffed on the low-budget-production-invaded-by-zombies concept briefly in Diary of the Dead (2009). But the idea sparks some formal bravado—namely, it unfolds over an unbroken 37-minute take that follows its actors in and around the installation.

The glorious B-movie made with cheapo make-up effects and life-imitates-art ironies soon ends, as the hero of the story has escaped the zombies by dismembering them all with an ax. At this point, you might think to check your watch. How much time has passed? You paid for a 90-minute experience. Were all those buckets of blood and frenzied, winking camera movements rendered with enough energy to prove the adage time flies when you’re having fun? Certainly, similar zombie comedies, from Shaun of the Dead (2004) to Zombieland (2009), pass by at breakneck speed, supplying the viewer with an exhilarating blend of guffaws and gasps—two of the most instinctual reactions the cinema can give us. But aside from the occasional Fido (2007) or Burying the Ex (2015), the subgenre hasn’t produced many memorable entries. Ueda’s film not only revives the DIY infectiousness of low-budget horror, but it will doubtless inspire young filmmakers to attempt their own microbudget projects too.

Indeed, the low-fi pleasures of One Cut of the Dead give way to the fictionalized backstory of its making, starting a month earlier. The transition, at first, may prove difficult to reconcile. The urgent and minimalist filmmaking of the first portion turns into the stuff of a Japanese television drama, where Hamatsu plays a journeyman director who sells his talents as “fast, cheap, but average.” A television network exec offers him a job making a 30-minute short film, but it must be done in a single shot. That’s challenging enough, but the film will also air on live television. He laughs at first at the very notion, until he realizes they’re serious. He accepts the job, and the viewer watches as he writes and rehearses the film-within-a-film we just finished. Ueda shows us the development of the end product, introducing us to the actors behind the characters, and the behind-the-scenes drama that goes into the filmmaking process. For a time, much of this second act might seem as though the family relationships and professional dynamics presented therein couldn’t possibly outdo the kinetic schlock of the opening sequence. But that’s where you’d be wrong.

The final third of the film follows the live shoot. Ueda creates a wildly entertaining layered effect, where, because we know how the final film looks, we expect that everything about its making will go as smoothly as it appeared. Instead, Ueda shows us how resourcefulness and compromise become a director’s greatest attributes, as everything breaks down minutes before the broadcast. Actors must be replaced, while other performers have issues ranging from drunkenness to diarrhea. Whole scenes and plotlines must be improvised, sometimes awkwardly. For the viewer, it carries out riotously, sparking our memory of the surface text from earlier. Now we see the in-film extratext, where nothing goes as planned but everything miraculously comes together. There’s also tenderness to these scenes. The director’s wife (Harumi Shuhama), a retired method actress, agrees to play a role at the last minute, and her improvisations account for some of the film-within-a-film’s most hilarious eccentricities. Their daughter (Mao), a film fanatic and aspiring director, also has an opportunity to bond with her father through the production, making for an aww-inducing finale.

At any given point during the first and last thirds of the film, it’s impossible not to think about the timing and coordination required by Ueda’s team. Achieving a 37-minute shot, and what’s more, an entertaining and funny story within that shot, would have been enough. But then he takes a step back and shows us another tier, as if we weren’t already impressed. The timing to achieve both layers at once is downright incredible. Ueda allows the viewer to discover a good horror film, and then we rediscover it from behind the camera, and suddenly it grows and deepens. Somehow the throwaway moment in the opening where an actress talks about her self-defense classes becomes a joke on multiple levels. The vomiting zombies, too, have an entirely new meaning. Along the way, One Cut of the Dead satiates the viewer with the easy pleasure of a horror-comedy before transitioning into something more, and what seems like a plodding mid-film interlude delivers a series of setups that pay off more than we could possibly anticipate.

At any given point during the first and last thirds of the film, it’s impossible not to think about the timing and coordination required by Ueda’s team. Achieving a 37-minute shot, and what’s more, an entertaining and funny story within that shot, would have been enough. But then he takes a step back and shows us another tier, as if we weren’t already impressed. The timing to achieve both layers at once is downright incredible. Ueda allows the viewer to discover a good horror film, and then we rediscover it from behind the camera, and suddenly it grows and deepens. Somehow the throwaway moment in the opening where an actress talks about her self-defense classes becomes a joke on multiple levels. The vomiting zombies, too, have an entirely new meaning. Along the way, One Cut of the Dead satiates the viewer with the easy pleasure of a horror-comedy before transitioning into something more, and what seems like a plodding mid-film interlude delivers a series of setups that pay off more than we could possibly anticipate.

It’s tempting to call One Cut of the Dead too clever for its own good, but that negates the exhilaration of the experience. After watching the film, I thought about how some of my favorite books are about the filmmaking process and stories of troubled productions. I thought about various Welles biographies and their grim tales of Hollywood executives ordering alternate cuts of his work. I thought about his daring improvisations and productions that carried on for years due to countless problems. One of the reasons I love film history is learning about how, despite looking like intentional masterworks, even titles like Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey have the same chaotic behind-the-scenes quality as a homemade zombie movie. Reading historical and biographical accounts of my favorite films and directors has taught me that every completed film is just a happy accident. Ueda captures that idea in film form, offering a horror-comedy, a behind-the-scenes drama, and a sort of mockumentary all at once. It’s a love letter to the magic that can come out of filmmaking chaos, and it might even be a mild masterpiece too.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review