Reader's Choice

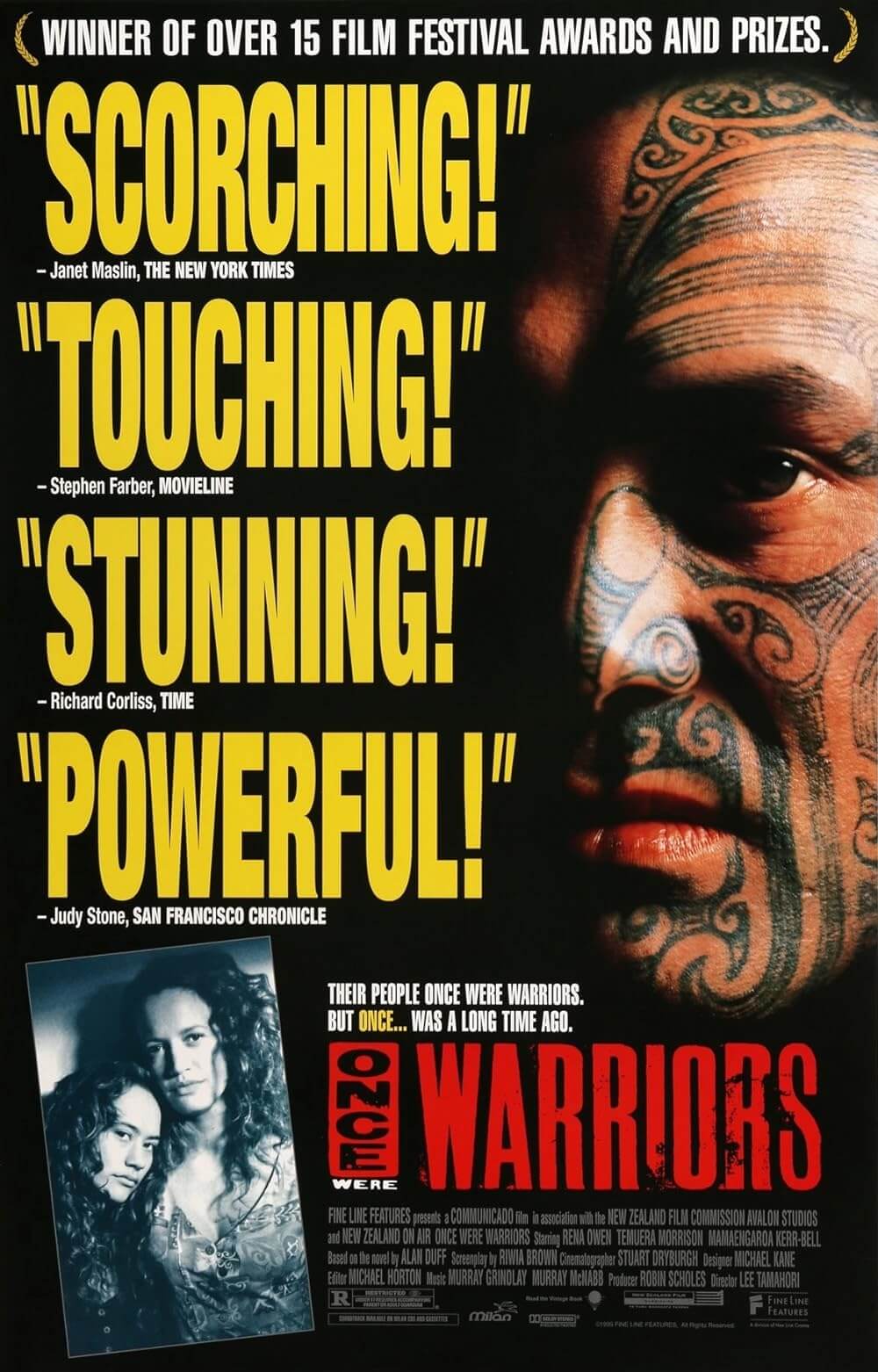

Once Were Warriors

By Brian Eggert |

Once Were Warriors opens with an idyllic image of the New Zealand coast and the country’s natural, mythical beauty. In a familiar but no less effective visual device, the shot pulls back to reveal the image is nothing more than a billboard—the visual splendor is pure marketing. The actual setting is a noisy sprawl of weathered concrete, graffiti, chain-linked fences, and the skeletal remains of forgotten automobiles. Situated in a state housing project and struggling to survive in this environment, the Hekes, a Maori family headed by Jake (Temuera Morrison) and his wife Beth (Rena Owen), endure an urbanized wasteland that has become their way of life. Based on Alan Duff’s best-selling novel from 1990, Once Were Warriors reveals the grim reality of the urban Maori, where alcoholism and domestic violence threaten to define the culture. Lee Tamahori’s feature film debut offers a cross-section of abuses, making it a searing portrait of self-destructive behaviors, toxic codependency, and gut-wrenching tragedy. But within the trappings of a gripping human drama is a complex post-colonial message about returning to the heritage that once defined the Maori.

Many critics have siloed Once Were Warriors into a film about domestic violence, ignoring the significance of its remarks about Maori culture, history, and colonialism. Roger Ebert called it “an attack on domestic violence and abuse,” then continued: “But I am not sure anyone needs to see this film to discover that such brutality is bad. We know that. I value it for two other reasons: its perception in showing the way alcohol triggers sudden personality shifts, and its power in presenting two great performances by Morrison and Owen.” Ebert’s remarks echo among other reviewers at the time, who described the film as a “domestic drama” or “primarily a tale of domestic violence and child sexual abuse.” Alcoholism and abuse certainly contribute to the problem, as Jake jolts between passionately kissing his wife to shouting “fuck you” at her in the same exchange. However, the film has more on its mind than the situation in the Heke home. Although its surface text offers a look at abuse in urban Maori culture, the film also has a rich intertextuality whose implications reveal a society pushed to the brink by the lasting effects of colonialism.

Tamahori sets the tenor early on after Jake’s bar friends have followed him home for what has become a regular nightly blowout at the Heke’s place. When Beth talks back at one point, Jake, a brutish alpha male unafraid to take down even the most intimidating challenge, unloads on Beth in a fury of punches that their friends cannot stop. Morrison is a force of nature, charismatic in one moment, intensely wide-eyed and frightful the next. The next morning, after a night of continued beatings and sexual abuse from her husband, Beth awakens to the shame of her children’s frightened and disappointed glances. This is their routine, endured by Beth, observed by their five children. Their eldest son, Nig (Julian Arahanga), has already left the family to become a member of a tattooed gang called “Brown Fist,” finding the cruel gang more supportive than his father. The middle son, Boogie (Taungaroa Emile), is sent into social welfare custody, where an instructor (George Henare) begins to teach him about the discipline required to be a true Maori warrior—a discipline his father lacks.

Any hope that the family might survive together is disrupted by a heartbreaking road trip sequence in the second act. Beth convinces Jake to take the family and visit their son Boogie in the detention center. When they stop to collect Nig, the newly christened gang member flounders for the briefest of moments—too long, as it turns out, for Jake. The impatient father speeds off, leaving his oldest son behind. On the way to see Boogie, the family visits Beth’s childhood home, a traditional Maori village in the countryside. Though the spot offers memories of a better time for Beth, it opens old wounds for Jake, whose ancestors were turned into slaves by warring tribes. Colonizers have displaced Jake and, in a sense, his own people have done the same, and his immutable anger and unresolved self-pity are the results. As the road trip continues, he convinces Beth to stop at the local tavern for “just one” drink, and before long, their pleasant trip has ended with Jake proving his cruelty and selfishness are part of his irrepressible cycle of behavior. No matter how disappointing and destructive Jake’s behavior may be, Beth remains at his side.

It’s their eldest daughter, the 13-year-old Grace (Mamaengaroa Kerr-Bell), who snaps Beth out of her complacency. She sees her father’s alcoholism and violence most clearly, and because of it, her contempt for her mother grows. When Grace asks her mother why she tolerates Jake’s behavior, she gets the logline of a domestic abuse victim in a patriarchal culture: “It’s a woman’s lot, that’s all. One day you’ll understand.” Jake and his friends treat women like servants and playthings, even reminding Beth and Grace to keep their place if they show disrespect. This patriarchal dynamic is relatively new in Maori culture following the introduction of Christian ideologies by European colonists, leaving Maori women dependent on their husbands in a trend that transformed the traditionally strong roles women played in Maori culture more than a century ago. And so, Grace’s fate symbolizes how the Maori spirit has suffered under urbanization. She is the eventual victim of Jake’s friend, the sleazy “Uncle” Bully (Cliff Curtis), and her sexual violation, combined with her parents’ unwillingness to protect her, leave her in a state of suicidal despair. Of course, similar to the emergence of a violently male-dominated culture, many of the characteristics of Maori culture addressed in Once Were Warriors have only emerged since the advent of European colonialism.

The Maori population arrived in New Zealand around 1300, having emigrated from Polynesian islands. They established their tribal culture and became the first settlers and sole inhabitants of the island country, where their development of agriculture and a warrior culture found a coexistence between the land and their people. That ended with the arrival of European colonizers in the nineteenth century, their ambitions set on whaling, sealing, and bringing Western civilization to the tribal community. The British invaded and, in the mid-1800s following the Maori Wars for land, assumed control of the country. Western influences over the local culture spread with the urbanization of New Zealand after World War II, which drew many Maori out of their rural communities and into the city. It was an active program by the ruling New Zealanders of European descent, known as Pakehas, to integrate the Maori into “civilized” areas. At the same time, Maori land continued to be sold and resistance efforts resulted in only minor victories; the effects of colonialism permanently displaced their cultural identity.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, the Maori population became a minority in their own country, driven into state assistance programs and ghettoized by the ruling Pakeha class. Today, the “people of the land” still struggle to maintain their ancestral spaces, while the levels of poverty and violence among the urbanized Maori have risen. In his assessment in The American Historical Review, critic James O. Gump observes, “A culture of poverty has spawned a culture of violence. Maoris constitute over 50 percent of New Zealand’s prison population, although only 10 percent of Zealanders are Maori.” However, these cultural outcomes have resulted from colonizers issuing false promises of integration in the postwar period. The so-called advantages of social and cultural integration, even “racial harmony,” promised by European settlers have proven false. As ever, the end of formal colonization results in a lasting, and more effectively destructive cultural colonization, wherein the oppressive socioeconomic influence has gradually eaten away at Maori identity.

The historical and cultural contexts driving Once Were Warriors ensure its status as vital anti-colonialist cinema, though the central narrative has the makings of a familiar social drama. Tamahori’s treatment blends a gritty and confronting piece of reality with a need to raise awareness about a marginalized culture. He places the viewer in the middle of scenes filled with intoxicated energy, highs of initially infectious male-bonding and song-singing, which at any moment can, and often do, flip like a switch into disturbingly violent posturing and beatings. This is a film of manic highs and lows. Most of the action takes place in two locations: the warehouse bar called the Royal Tavern and the ramshackle home of Jake and Beth, often the site of a rowdy afterparty that devolves into scenes of boozing and shocking physical abuse, and later, a scene featuring the rape of a minor and her eventual suicide. It becomes a claustrophobic space to escape from in a trigger-warning-of-a-film that more than once proves challenging to watch, making other dysfunctional family films look tame by comparison.

For a film with such challenging subject matter, Once Were Warriors set box-office records in New Zealand for its rare depiction of Maori subjects. Tamahori quickly went Hollywood with a series of major studio pictures, for better or worse. After the L.A. noir Mulholland Falls (1996) and the David Mamet-scripted survival picture The Edge (1997), Tamahori moved into franchises, including a James Patterson thriller and a James Bond actioner. But the bloated costs and flashy movie stars of Tamahori’s later output result in workmanlike efforts, absent of the vital filmmaking on display in his debut. Urgent camerawork by Stuart Dryburgh on Once Were Warriors immerses the viewer in scenes that switch from loving to cruel in an instant, whereas the sound design inches toward moments of violence with a humming sound as Jake’s rage builds— an aural cue that lingers just under the surface, recalling a swarm of bees that grows enraged. It’s a sound that warns of the tirade of hideous insults and pummeling to follow. Unfortunately, the filmmaker of Maori and British parentage wouldn’t return to his country and people as subject matter until 2016’s Mahana, and he’s never matched the energy of his filmmaking here.

For a film with such challenging subject matter, Once Were Warriors set box-office records in New Zealand for its rare depiction of Maori subjects. Tamahori quickly went Hollywood with a series of major studio pictures, for better or worse. After the L.A. noir Mulholland Falls (1996) and the David Mamet-scripted survival picture The Edge (1997), Tamahori moved into franchises, including a James Patterson thriller and a James Bond actioner. But the bloated costs and flashy movie stars of Tamahori’s later output result in workmanlike efforts, absent of the vital filmmaking on display in his debut. Urgent camerawork by Stuart Dryburgh on Once Were Warriors immerses the viewer in scenes that switch from loving to cruel in an instant, whereas the sound design inches toward moments of violence with a humming sound as Jake’s rage builds— an aural cue that lingers just under the surface, recalling a swarm of bees that grows enraged. It’s a sound that warns of the tirade of hideous insults and pummeling to follow. Unfortunately, the filmmaker of Maori and British parentage wouldn’t return to his country and people as subject matter until 2016’s Mahana, and he’s never matched the energy of his filmmaking here.

If the film wavers at all, it’s in the screenplay by Riwia Brown, which features the occasional line of stagey dialogue. When Beth finally takes a stand against Jake’s behavior in the climactic scenes, announcing her plan to take their children back to her village, she declares, as if for the camera in a triumphant moment: “If my spirit can survive living with you for 18 years, then I can survive anything—‘cause living with you is like living in hell!” Fortunately, the actors are superb, and their naturalism overcomes most of the artificial dramatics of the screenplay, allowing for the film’s themes to emerge naturally. In the end, Once Were Warriors settles on the idea that the greatest way to move forward is reaching into the strength of the past. It’s a contradictory notion to be sure, but without the preservation of their history and traditions, Maori culture would be absorbed, digested, and forgotten by cultural colonization. It is the persistent, tragic challenge of any colonized people, who were not granted the opportunity to transition into a modern world in their own time, to actively embolden themselves. Once Were Warriors speaks to this idea with raw emotion and cultural insight.

(Editor’s Note: This review was suggested and commissioned on Patreon. Thank you for your support, Lee!)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

Thank you for visiting Deep Focus Review. If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your movie watching—whether it’s context, insight, or an introduction to a new movie—please consider supporting it. Your contribution helps keep this site running independently.

There are many ways to help: a one-time donation, joining DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or showing your support in other ways. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review