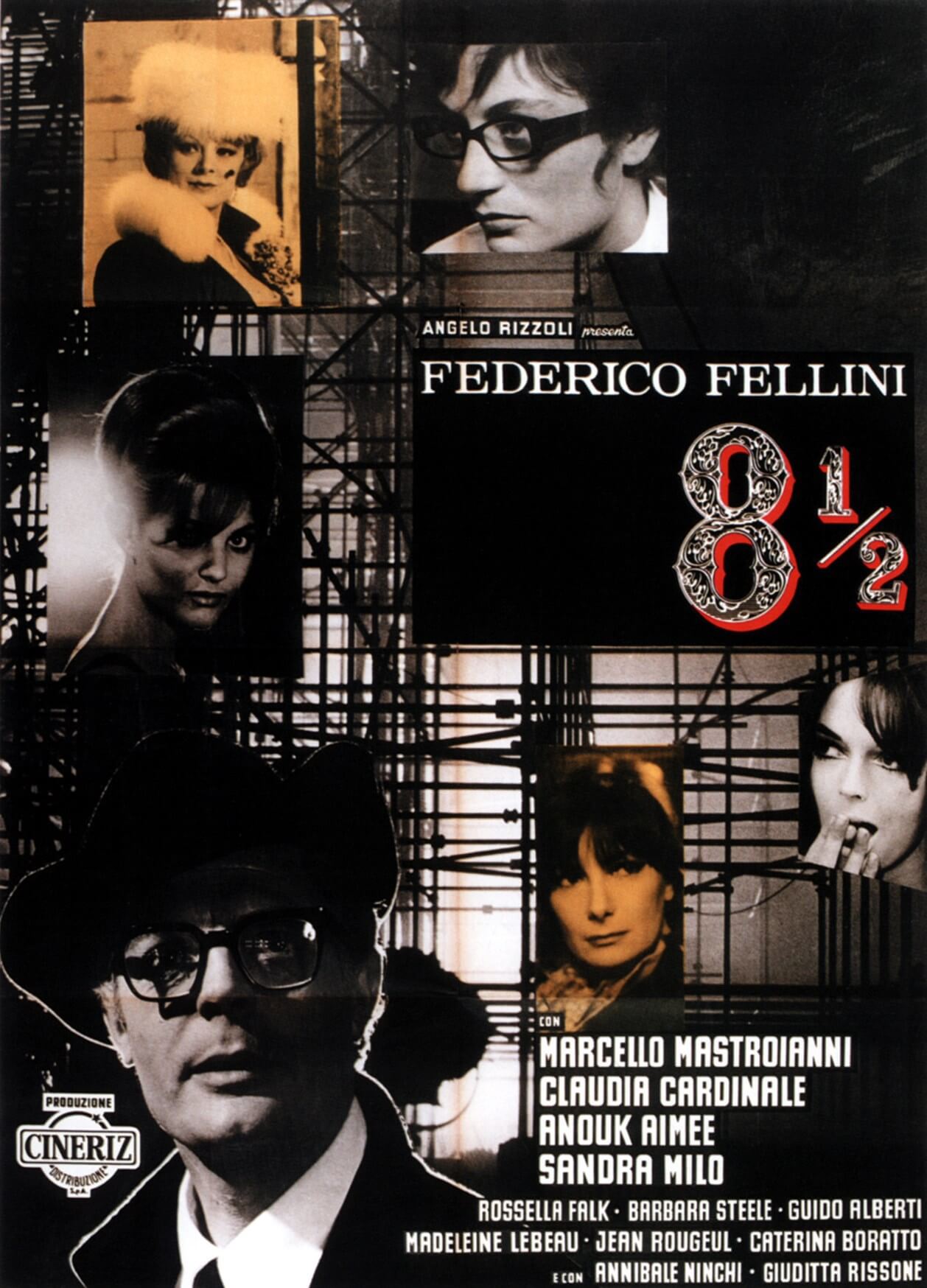

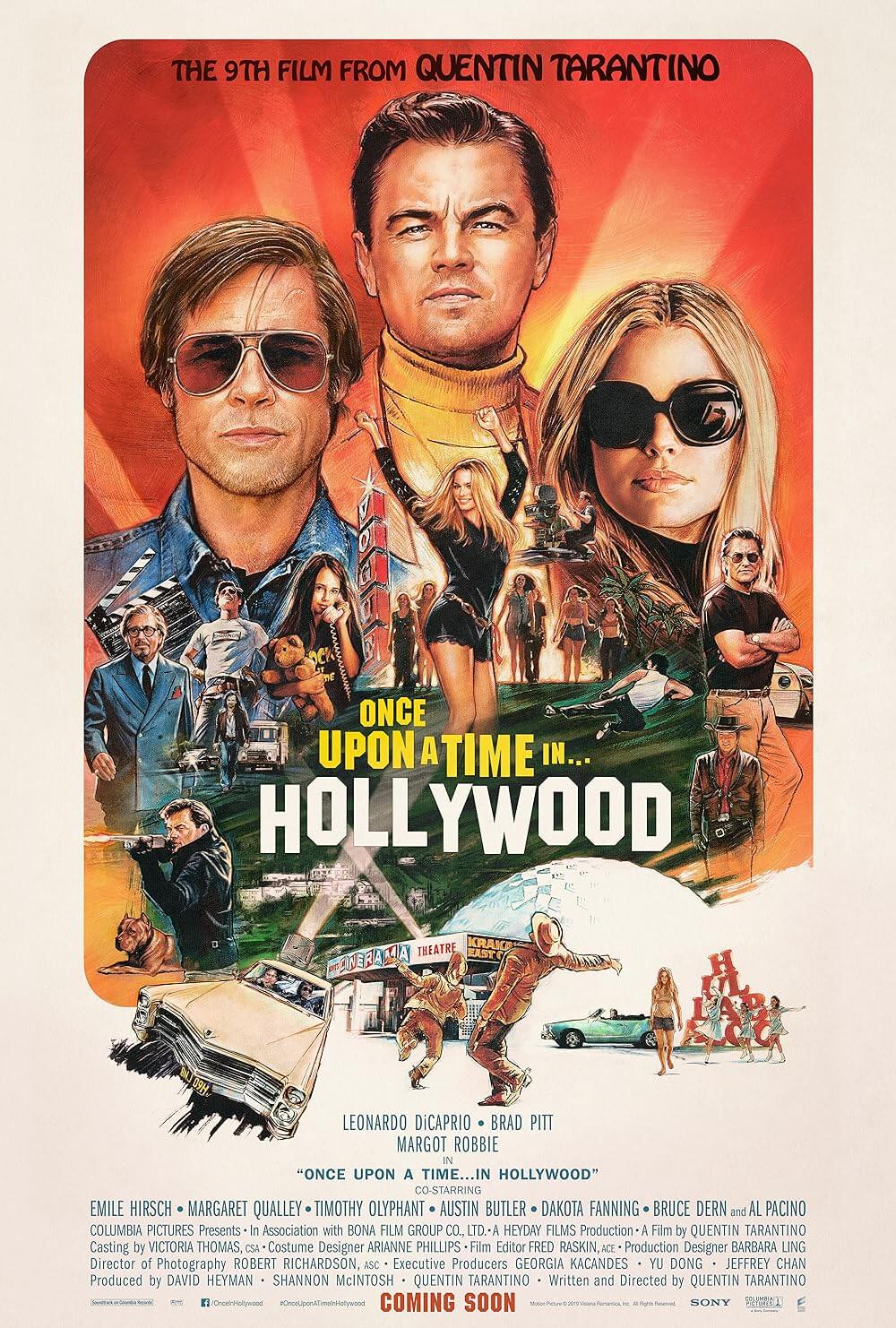

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood

By Brian Eggert |

Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood luxuriates in its setting of 1969 Los Angeles. His characters drive around in leisurely scenes, passing by forgotten restaurants and Hollywood Boulevard moviehouses that advertise obscure titles from yesteryear, while unremembered songs like Los Bravos’ “Bring a Little Lovin’” light up the radio. The atmosphere, a cultural chasm separated by the lingering 1950s optimism and an emergent streak of hippie counter-culture, is evident in the top movies at the box-office that year. The old guard of the studio system put out The Love Bug and Paint Your Wagon, whereas independent mavericks spoke to an emboldened new audience with Easy Rider and Midnight Cowboy. The reality of the era’s political strife and oppressive paranoia was easier to take given the pockets of free love, mind-expanding drugs, and harmony represented by Woodstock. At the same time, the moon landing promised that humankind could reach the expansive universe beyond our earthly realm. It’s a mythical time that has, in some form or another, shaped Tarantino’s life and each of his films—though he was just six when his ninth feature takes place, he spent much of his youth soaking up the culture of the 1960s. Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is Tarantino’s great gift to the audience; it’s a chance to see the era through his eyes, but it’s also his chance at historical revenge.

In her essay The White Album, Joan Didion wrote that the spirit of the 1960s “ended abruptly on August 9, 1969,” the day after three members of the so-called Manson Family walked up Cielo Drive to the home of Roman Polanski, who was in Europe preparing his next picture, and his eight-months-pregnant wife, Sharon Tate. The bloody and tragic result of that encounter festers in the back of the viewer’s mind while watching Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, filling us with a horrible sense of anticipation. But Tate, played by Margot Robbie, is a peripheral figure in the overall film, a detail that has earned Tarantino scorn in some circles. Detractors arguing against the film from the perspective of current sociopolitical concerns ignore that Tarantino has already given us incredible women such as The Bride and Jackie Brown. They fail to see why Tate’s role is almost purely symbolic. She enjoys watching and being in movies, listening to good music, and driving around the Hollywood hills at top speeds with her husband (Rafal Zawierucha). In a particularly charming sequence, Tate visits a cinema showing The Wrecking Crew, in which she plays the klutz who’s really a trained spy, and she beams every time her performance causes a laugh from her fellow moviegoers. Tate is less central to the story than a shining product of the era and its potential. Her fate in the film—a tight-lipped secret that will be discussed in the paragraphs below—is essential to its raison d’être. Not only does Tarantino allow his audience to inhabit this world, he jealously protects the era, epitomized by Tate, from an abrupt end.

Throughout this two-hour-and-forty-minute saga, which is more of a hangout movie than the epic title implies, Tarantino saturates the viewer in the 1969 Hollywood milieu. At the top is Sharon Tate, whose husband just released Rosemary’s Baby to widespread acclaim and fervor, while headed toward the bottom is Rick Dalton (Leonardo DiCaprio), whose heyday as the star of a few B-movie actioners, and the hero of the Western series Bounty Law, has given way to a dwindling career of guest appearances on episodic television, usually as the villain. As a producer played by Al Pacino explains, if Rick keeps playing the heavy, the audience will begin to associate him with bad guys, and he’ll fall out of favor. There’s the option of going to Europe to star in Italian Westerns, but Rick wants to remain where it’s at, in Hollywood. Though he’s not entirely washed up, Rick drinks too much and spends most of his time with his regular stunt man, Cliff Booth (Brad Pitt)—who also serves as a personal assistant and housesitter, and he might be Rick’s only and most dependable friend. Together, they drive around Los Angeles, bullshit on the set of his latest gig, and engage in an endearing form of male camaraderie, while the viewer absorbs the details: the painted movie posters, the television shows, the predominance of single-screen theaters, the classic cars, and the excellent music (Tarantino has given us another vital soundtrack).

Throughout this two-hour-and-forty-minute saga, which is more of a hangout movie than the epic title implies, Tarantino saturates the viewer in the 1969 Hollywood milieu. At the top is Sharon Tate, whose husband just released Rosemary’s Baby to widespread acclaim and fervor, while headed toward the bottom is Rick Dalton (Leonardo DiCaprio), whose heyday as the star of a few B-movie actioners, and the hero of the Western series Bounty Law, has given way to a dwindling career of guest appearances on episodic television, usually as the villain. As a producer played by Al Pacino explains, if Rick keeps playing the heavy, the audience will begin to associate him with bad guys, and he’ll fall out of favor. There’s the option of going to Europe to star in Italian Westerns, but Rick wants to remain where it’s at, in Hollywood. Though he’s not entirely washed up, Rick drinks too much and spends most of his time with his regular stunt man, Cliff Booth (Brad Pitt)—who also serves as a personal assistant and housesitter, and he might be Rick’s only and most dependable friend. Together, they drive around Los Angeles, bullshit on the set of his latest gig, and engage in an endearing form of male camaraderie, while the viewer absorbs the details: the painted movie posters, the television shows, the predominance of single-screen theaters, the classic cars, and the excellent music (Tarantino has given us another vital soundtrack).

Meanwhile, Rick starts to recognize his failings in the protagonist of a pulp fiction paperback he’s reading. As Rick explains to his eight-year-old costar, an uncommonly composed and method child actor (Julia Butters) whom he meets on the set of his latest guest spot, the book is about a past-his-prime horsebreaker: “He’s coming to terms with what it’s like to become slightly more useless each day.” The same is true of Rick, whose frequent coughing fits and hangovers stem from the omnipresence of cigarettes and alcohol in his life, whereas his anxieties about his career have manifested in the occasional stutter and forgotten line. The state of Rick’s career and the meaning it gives his life hold sway over the audience. He’s a sad figure whom we want to succeed, to the extent that when he finally delivers what his costar calls “the best acting I’ve ever seen,” the scene becomes triumphant enough to induce tears (both Rick’s and the audience’s). At the same time, Tarantino creates his own behind-the-scenes lore in support of his devotion to the period, such as how he explores the subculture of stunt workers. Kurt Russell, playing a far less deranged stuntman in this QT picture, heads a crew of daredevils alongside his on-screen wife, played by real-life stuntwoman Zoë Bell. And they’re none too fond of Cliff given a disturbing rumor about his past.

While Rick is playing a cowboy on the set, the film follows Cliff’s amblin’ around Hollywood in leather moccasins, living the takes-no-shit modern cowboy life. Tarantino has talked at length about his love of Westerns; he’s made two of them, and he’s evoked them in his other films countless times. Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is another sort of Western, and Cliff is the lone gunman who saunters into a frontier town, makes enemies, and brings a dead reckoning in the finale. In a brilliant extended sequence, Tarantino intercuts Rick on the Western show’s set with Cliff’s very own trip to a dusty complex of saloons, stables, and paranoid townsfolk. When Cliff agrees to give a hitchhiking hippie (Margaret Qualley) a ride home, he discovers she lives with several other vagabonds on the Spahn Movie Ranch—once a working ranch and setpiece for movie Westerns. Now it’s the home of Charles Manson (Damon Herriman, mostly absent) and his brainwashed devotees, who train their pistol eyes on Cliff as he explores his former stomping grounds and insists on speaking with its blind and elderly owner (Bruce Dern). The sequence is shot with all the style, tension, and surroundings of a Western, complete with a showdown opposite Dakota Fanning’s unsettling Squeaky Fromme. Of course, Cliff can handle himself, as demonstrated earlier when he encounters Bruce Lee (Mike Moh) on the backlot. And afterward, one can’t help but wonder if Rick realizes that his friend is a real cowboy, while he just plays one on TV.

Unlike many of Tarantino’s recent films, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is not composed of several individual sequences that each gradually crescendos to a violent resolution, although an argument could be made that the entire film is one long sequence that builds to a decisive moment. The laid back quality of the film recalls his underrated Jackie Brown, where the characters and mood take precedence over the machinations of the plot. Some may find his rollicking in the period dull, but another sort of viewer will cling to every moment with the same gleeful enthusiasm as the writer-director—even if we never experienced the setting first-hand, its energy and allure are infectious. And yet, Tate’s death remains in the back of our minds each time she appears onscreen, as Robbie’s free-and-easy presence incites a sense of dread for its eventual loss. But Tarantino uses our expectations, playing with reality and fiction to deliver a conclusion that redirects our terror. Though about two hours of the film takes place in February 1969, the final act leaps forward several months to August, just as Rick and Cliff complete their sojourn to the Italian film industry. Rick is now married and unable to keep Cliff on the payroll, and their final night together is fateful to be sure.

Once again, Tarantino has made a film that exacts historical revenge. The dish best served cold has been a persistent theme in his work, from the Bride’s laundry list of future victims in Kill Bill to the assorted retaliations throughout The Hateful Eight. But Tarantino’s historical revenge films have rewritten history with a view toward catharsis and fictional poetic justice. His Nazi-killing band of Jewish-American soldiers in Inglourious Basterds put an end to the Third Reich when they unleashed a barrage of bullets into Hitler’s face, while his former slave turned bounty hunter in Django Unchained brought ruin to a vile plantation. Once Upon a Time in Hollywood offers another brand of historical revenge in service of Tarantino’s beloved era, whose death he refuses to depict. The film is a loving ode, but it’s also a denial of historical fact, and in that, a passionate commitment to keeping the spirit of Los Angeles in 1969 alive—a spirit personified by Tate. That the Manson Family never reaches the Polanski home in the film becomes a rousing turn of events, unleashing both the full force of Cliff and Rick, thus promising, in this alternate reality of Tarantino’s creation, that no such trauma will bring the era to a close.

Once again, Tarantino has made a film that exacts historical revenge. The dish best served cold has been a persistent theme in his work, from the Bride’s laundry list of future victims in Kill Bill to the assorted retaliations throughout The Hateful Eight. But Tarantino’s historical revenge films have rewritten history with a view toward catharsis and fictional poetic justice. His Nazi-killing band of Jewish-American soldiers in Inglourious Basterds put an end to the Third Reich when they unleashed a barrage of bullets into Hitler’s face, while his former slave turned bounty hunter in Django Unchained brought ruin to a vile plantation. Once Upon a Time in Hollywood offers another brand of historical revenge in service of Tarantino’s beloved era, whose death he refuses to depict. The film is a loving ode, but it’s also a denial of historical fact, and in that, a passionate commitment to keeping the spirit of Los Angeles in 1969 alive—a spirit personified by Tate. That the Manson Family never reaches the Polanski home in the film becomes a rousing turn of events, unleashing both the full force of Cliff and Rick, thus promising, in this alternate reality of Tarantino’s creation, that no such trauma will bring the era to a close.

Although watching a Tarantino film can sometimes feel like a game of spot the reference, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood does not have the pastiche quality of some of his work—though the nods are there for those looking, they’re arguably more esoteric. But his approach, as usual, is vibrant and alive. He and cinematographer Robert Richardson have filled the picture with a myriad of film styles, aspect ratios, and various uses of color and black-and-white photography. They recreate scenes from The Great Escape or television series The F.B.I. with loving attention to detail or interrupt the narrative with Kurt Russell’s omniscient narrator. Watching it is a joyful experience rooted in the appreciation of great, playful filmmaking and acting. DiCaprio is brilliant at capturing the profound insecurities of an actor, while Pitt offers a cucumber cool figure on the sidelines who prefers not being in the spotlight. When they’re together, the warmth of their friendship is unquestionably sincere. Outside of the terrific leading men, Tarantino has populated every scene with an ensemble of his regular players and a few new ones: Michael Madsen, Timothy Olyphant, Luke Perry, Damian Lewis, Emile Hirsch, Scoot McNairy, Lena Dunham, and plenty others.

Tarantino immerses the viewer in Hollywood lore and everyday life, while his revisionist history functions as a testament to his adoration of the period and a fanciful rejection of what happened to Tate and her friends—and how that meant the end to this beloved era. Those committed to historical accuracy will surely feel that Tarantino has somehow betrayed reality, but then, what sane person looks for an accurate account of history in a Hollywood film anyway? Tarantino’s work of historical revenge does not make arbitrary alterations; it provides a beautiful, even tender-hearted sense of defiance and fantasy. In another way, it also might be the summa of his work, as it encapsulates many of his themes and preoccupations, from foot fetishism to the mythologizing of forgotten cinema in the modern cultural consciousness. Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is Tarantino at his most human and mature; much like Jackie Brown, he relies less on referential material and more on exploring rich, fully developed characters who seem to live and breathe. Surprisingly emotional and compassionate, it’s an elegy to a bygone era and a sheer pleasure to behold.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review