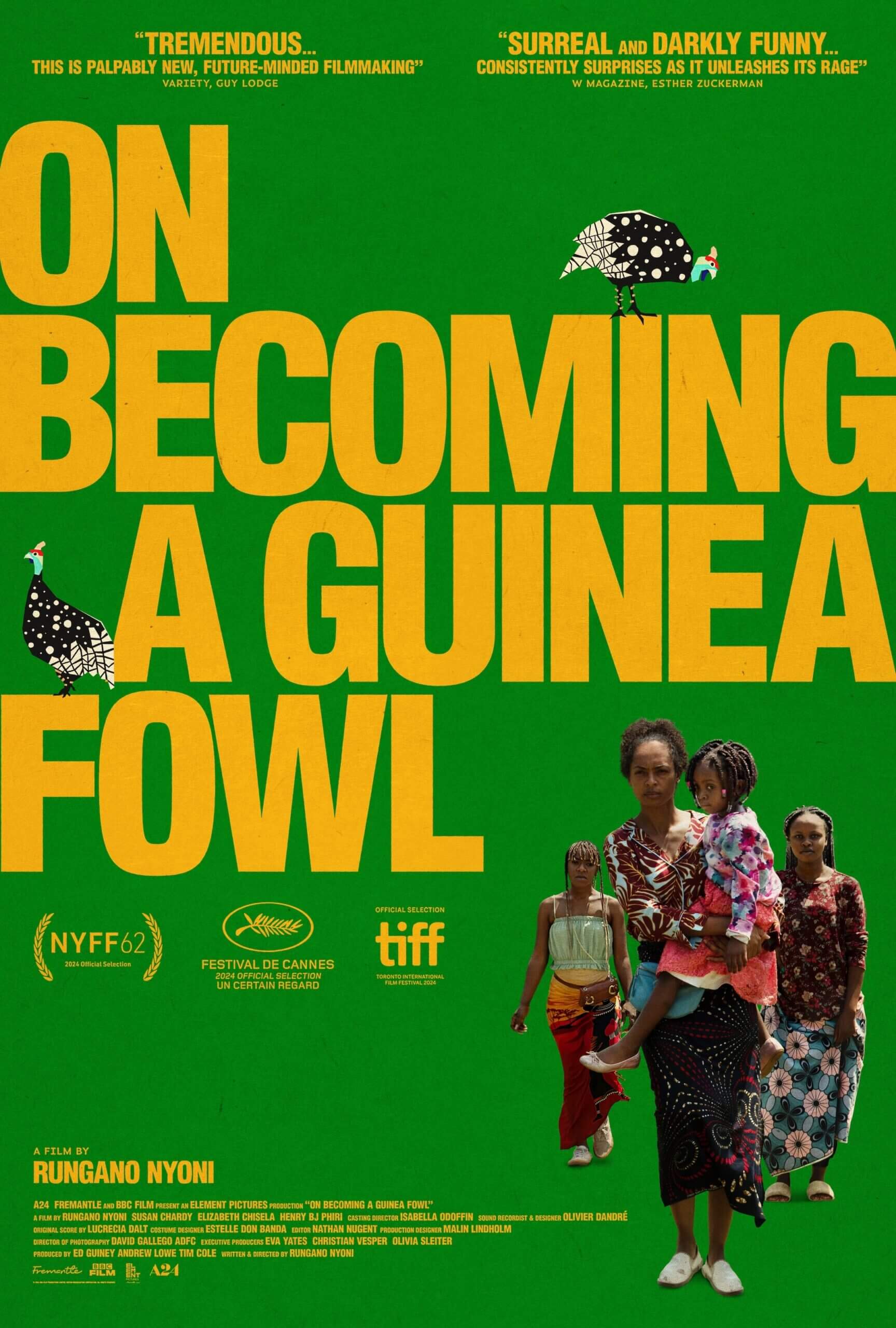

On Becoming a Guinea Fowl

By Brian Eggert |

Note: This film was screened for the Twin Cities Film Fest and reviewed on October 19, 2024. A24’s limited theatrical release begins on March 7, 2025, and will expand in the weeks to follow.

A children’s show called Farm Club—what looks to be Zambia’s answer to Sesame Street—features in the second film by Rungano Nyoni, On Becoming a Guinea Fowl. The show teaches its audience of children about guinea fowls, describing them as “chatty creatures” that make noise when “there’s danger about.” The show calls them useful to “all creatures on the Savanna” for their squawking at the sight of a predator, alerting other animals when a lion or hyena appears in the area. Nyoni’s family drama uses the bird as a metaphor to raise concerns about sexual abuse, the central theme of her film. Her approach contains flourishes of magical realism and black-as-pitch humor, telling a story that unfolds in an unpredictable way, with a sense of acknowledgment and critique about how the family at the center questions the abuser yet creates a space for abusers to continue. Nyoni grapples with heavy subject matter, and while her film’s humor and dreamlike touches might seem to undermine those concerns, they only strengthen her commentary.

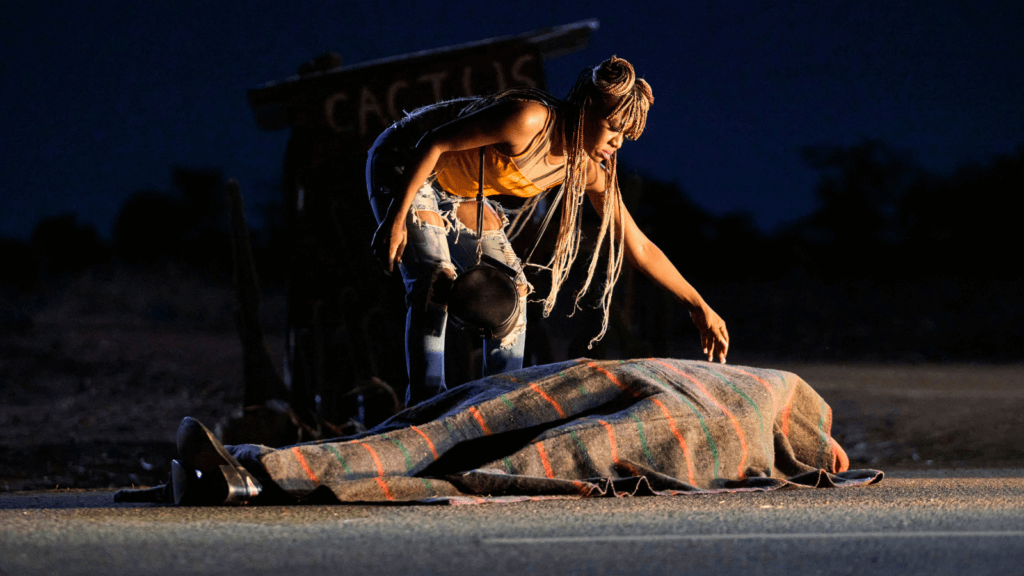

Susan Chardy plays Shula, who first appears decked out in a puffy costume, glittery hat, and sunglasses, headed to a party late at night. Her appearance cuts through the seriousness and injects surreality into what she sees while driving: her Uncle Fred lying dead in the middle of Kulu Road. Strangely calm at the sight, Shula sees visions of her younger self near her uncle’s body, which was dragged there, facing up, by sex workers at a nearby brothel. Not far from the body, a Christian billboard preaches “Miracles: Healing & Deliverance” with the image of a preacher and white dove displayed in grotesquely cheery fashion under the circumstances. Whether any healing or deliverance are realized within the film, well, that’s up for debate. Neither the Bemban culture to which Shula belongs nor the Christian one that influences her tribe offer many answers; they both have their ways of making it impossible to heal. After all, doctrines have a way of denying everything but themselves.

Whether it’s the inherently patriarchal nature of Christianity or, in Nyoni’s Bemban tribe, where it’s considered impolite to speak ill of the dead, religious and cultural influences have loopholes that allow for abuse. Shula, who has returned home to visit after some time away, finds herself trapped by these social mores and decorum. Her mother (Doris Naulapwa), Fred’s sister, refuses to speak ill of the dead and puts on quite a show over the loss. Shula’s wild cousin, Nsansa (Elizabeth Chisela), comes off as aggressively obnoxious at first, but the two learn they’ve both been victims of Uncle Fred, allowing them to form a bond sometime later. Her father (Henry B.J. Phiri) is reliable only in how unhelpful he remains. No wonder Shula feels trapped in the situation—both forced to organize the funeral and observe the family’s rites while trying to maintain a critical distance given her experiences.

Watching the funeral process through Shula’s eyes, one becomes aware of its frustrating gender dynamics. The days-long process honors the dead and gives the living a chance to celebrate what is good about them. The Bembas believe that every person is born with goodness; what happens to them in life is deemed circumstantial. So, in death, family and friends honor the dead’s goodness, ignoring everything else (a familiar enough concept). Uncle Fred’s sentimental obituary, which Shula translates over the phone, proclaims, “We have lost but heaven has gained.” Most of the elders, especially the men in Shula’s tribe, refuse to question Fred’s past behavior, dismissing why the sex workers might have dragged him into the street and quieting any voices that would dare bring out the truth. Instead, they encourage denial by focusing on the funeral ritual, which involves women bringing the men’s very specific dinner orders in a prompt fashion.

Chardy is excellent as the stone-faced Shula, whose refusal to show grief receives censures from the women in her tribe. After acting out a snaky performance to enter the family home (“Death comes slithering,” they declare), they want details and demand that Shula act out the scene. How was Fred’s body positioned? Were there any sticks or blood nearby? While everyone else cries and wails histrionically, Shula cannot. Others are not so composed. Her other cousin, Bupe (Esther Singini), tries to kill herself over the abuse. But Bupe’s mother tells Shula not to say anything about the real reasons for Bupe’s hospitalization and instead attributes them to malaria. This might be unlikely material for humor, but Nyoni finds laughs in curious places. When Shula first discovers her uncle’s corpse, her call to the authorities to report his death is met with an amusingly bizarre response. They won’t come by until the next day, they tell her, and further instruct her not to park next to the body to avoid any suspicions.

After a seven-year hiatus between her widely praised first film, I Am Not a Witch (2017), and On Becoming a Guinea Fowl, Nyoni proves her debut wasn’t a fluke. She’s an original voice with the capacity to weave specific dramatic questions about who’s responsible for allowing Fred’s behavior to persist for so long. Her film poses larger inquiries about accountability for abuse within religions and cultural systems. It’s a #MeToo film, in that sense, yet never resorts to soapboxing, even though, by the end, the message is unmistakable. The potent zoological metaphor that drives the film’s title is enough to underscore its warning and call to speak up against sexual predators, whether they’re your uncle, someone in your community, your priest, or otherwise. In that sense, it’s a harrowing and vital film with a distinct personality and playfulness that enriches the material. Hopefully, we won’t have to wait so long until Nyoni’s next film.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review