Old Joy

By Brian Eggert |

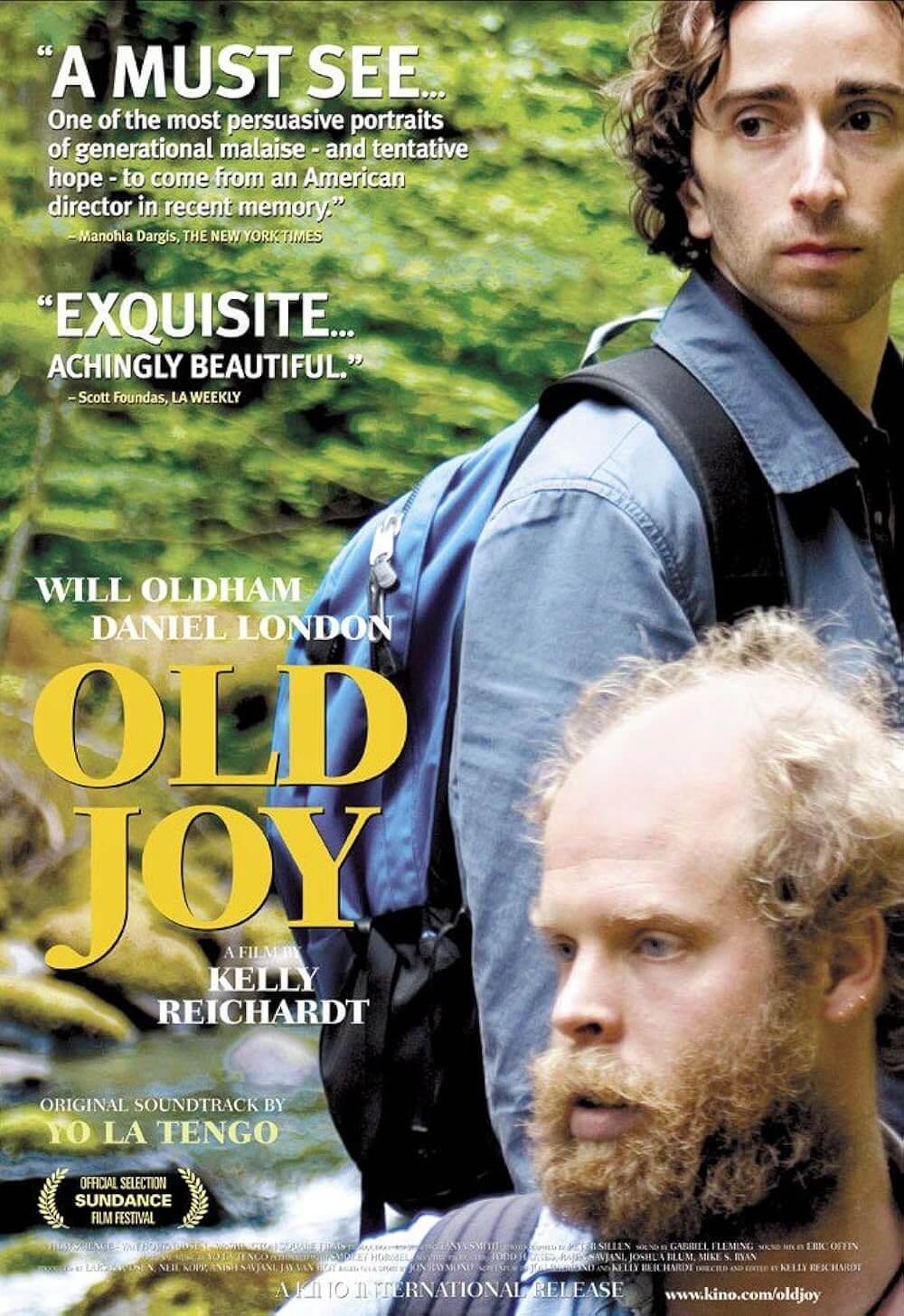

The setup of Kelly Reichardt’s Old Joy could be used for a far more conventional film: two old college friends get together after years apart for an overnight vacation of awkward exchanges and under-the-surface tension. It’s an odd couple scenario that could be reduced to stereotypes, but in the case of Reichardt’s treatment, the 2006 film operates within a careful state of nuance and lived-in characterizations. If the mini-major version of this story looks something like the abrasive Sideways (2004), Reichardt paints a portrait of masculinity among a certain segment of thirtysomethings that feels blazingly original, realistic, and delicate. And yet, its depiction of guarded intimacy has a political component situated in the self-satisfied left, who would rather live in an alienation of their own making than confront something unknown and therefore difficult. Old Joy has an unassuming complexity that doesn’t reveal itself without an acceptance that each detail in this two-hander has meaning, which is contained within weighted silences, evaded questions, and spoken half-truths. It’s an achingly sensitive film about two men quietly suffering in their own way, yet each of them struggles to acknowledge the full extent of their yearning.

The film opens as Mark (Daniel London), failing to meditate in the backyard of his suburban Portland home, receives a call from Kurt (Will Oldham), a long-absent friend who recommends a woodland hike to a secluded hot springs located somewhere in the forests of Oregon. The impromptu invite upsets Mark’s pregnant wife, Tanya (Tanya Smith), who tells him to do what he wants, which is obviously not what she wants. Already, the passive-aggressiveness is palpable. It will get worse. Ignoring his wife’s cues to escape his stifling home situation, Mark agrees to the trip and drives to meet Kurt, his liberal talk radio blaring about how conservatism is ruining America (you get the impression that today Mark would be proud to tell you that he’d vote for Obama for a third term). The free-spirited Kurt, not surprisingly, arrives late for their rendezvous, carting a wagon of supplies, sporting a beard and shabby clothes. He looks like a grungy Generation X man-boy who’s grown up but never changed. In another film, Mark and Kurt might fulfill common tropes, something akin to the male friends in I Love You, Man (2009), or various Judd Apatow productions. But Old Joy avoids pandering to the viewer with clichés of character by subverting our expectations with its embrace of human dimension.

It’s also tempting, albeit a mistake, to saddle Old Joy, or any of Reichardt’s films for that matter, with the label “mumblecore,” the sometimes-pejorative term used to describe microbudget independents of a certain ilk—the stuff of Andrew Bujalski, Joe Swanberg, Jay and Mark Duplass, and Lynne Shelton. Old Joy fulfills the movement’s penchant for realistic conversations, low-key drama, and characters adrift in loosely plotted stories. It even looks like a mumblecore project at times, employing a familiar aesthetic of inexpensive camerawork, natural lighting, and unfussy shots. But like most things in Reichardt’s film, what appears familiar and potentially predictable reveals itself to be far more complex. She is, after all, a director of minimalist dramas who layers intentionality into every flourish. Whereas mumblecore relies on improvisation and a rejection of standardized, commercially catering indie archetypes that prevail at Sundance, Reichardt’s work goes even further to thoughtfully considered human dramas that may look and feel small, but they invite consideration beyond the surface. Indeed, Old Joy is a film about characters who have so deeply repressed their dissatisfaction that it can only emerge in the isolation of Nature.

Almost immediately, after Kurt convinces Mark to drive them into the forest, the film settles into their friendship. Kurt lights up and continues to smoke marijuana through casual chit-chat about Mark’s father’s ill health or their favorite record store that has since become a smoothie shop. Long passages looking out the car window at the passing landscape are set to Yo La Tengo’s gentle acoustic guitar soundtrack. Underneath the easygoing conversation, however, are microexpressions on Mark’s face and hints of resentment for Kurt’s carefree lifestyle of crashing on couches and taking community college courses just for fun. Mark’s state of annoyance reaches an unspoken limit when Kurt forgets the exact location of the hot springs, forcing the two men into sleeping on discarded furniture in a makeshift campsite. Kurt doesn’t mind, as he’ll happily drink beer and shoot cans with a BB gun. Mark goes along with it politely, almost convincingly unbothered. He never blows up at Kurt or anything so dramatic, but he has a barbed way of asking questions that reflects his inner irritation—such as when he obviously humors Kurt, who struggles to explain a profound physics lesson. But rather than turn Mark’s resistance to confrontation into a source of cringe-comedy or even portray these character as ridiculous, Reichardt uses the tension to deepen the characters and our emotional investment.

All at once, Kurt announces, “I miss you, Mark. I miss you really, really bad. I want us to be real friends again. There’s something between us and I don’t like it. I want it to go away.” Another friend might see this as an opportunity to clear the air. Mark does the opposite; he reassures Kurt that their friendship is fine. But it’s as though a line has been crossed. The next morning at a diner, Mark talks to Tanya on his cell phone outside and apologizes for Kurt delaying the trip (“He thought he knew where it was, but remember who we’re dealing with”), while inside, Kurt makes fun of his friend for taking a call during breakfast. A moment later, Kurt reassures Mark that they’re close to the hot springs, confirming it with their server; Mark replies, “I never doubted you man,” in a tone of faux-encouragement. From here onward, Mark’s niceties sound even more hollow, and Kurt’s sense of loss over their friendship feels pronounced in Reichardt’s silences. It’s an uneasiness contrasted by the beauty of Pacific Northwest forests, where all appears serene. That awkwardness between them curiously fades after they reach the hot springs and strip down, and Kurt waxes philosophical about how “sorrow is nothing but worn out joy.” It’s a sentiment that allows both men to ease into their warm soak, listening to the sound of flowing water.

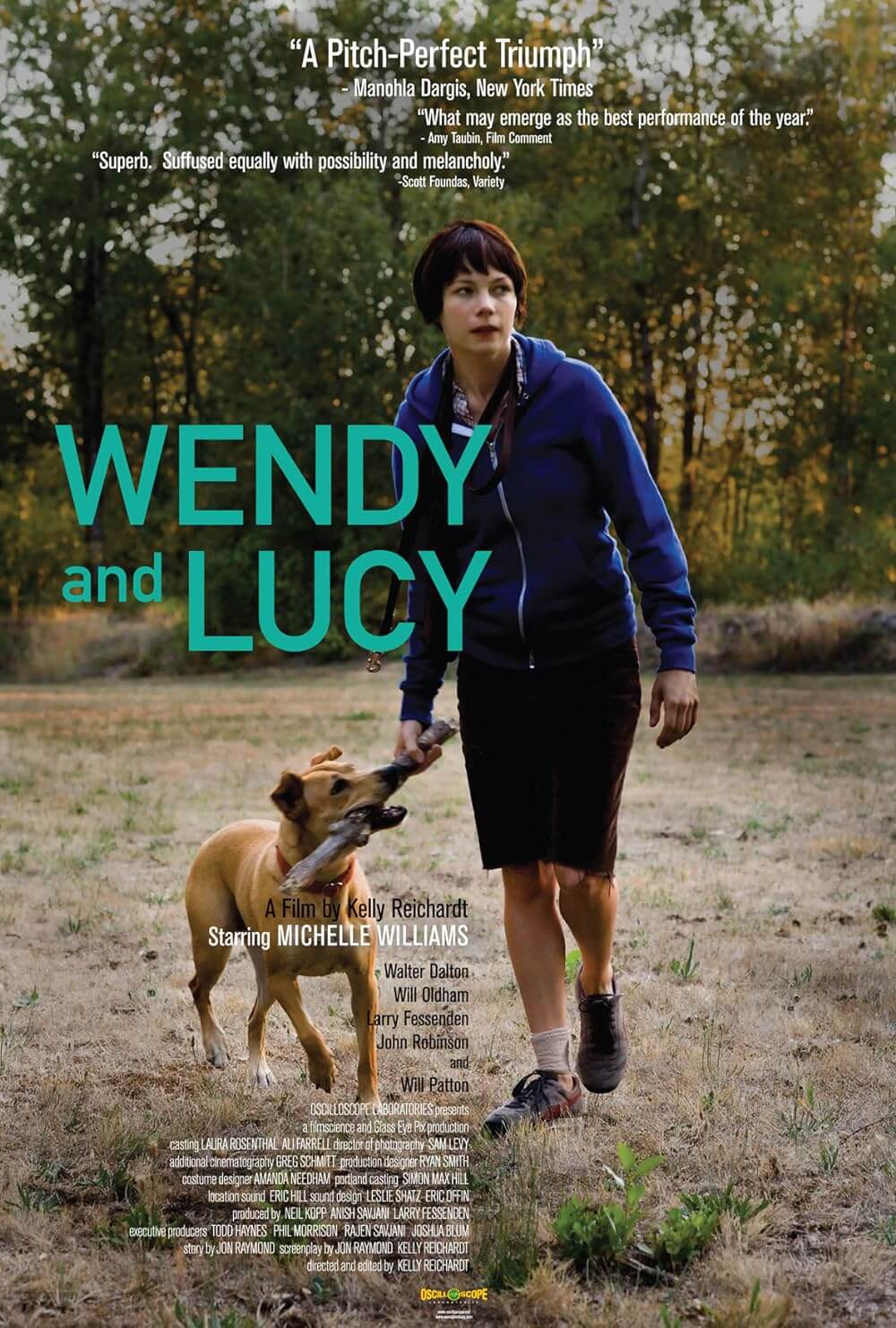

Old Joy is Reichardt’s second feature after River of Grass from 1994, a success that she followed with a few short films and some years of floundering. It wasn’t until she met author Jonathan Raymond, after being introduced by their mutual friend Todd Haynes, that she began her longstanding collaboration with the writer of nearly each of her films. Raymond wrote the original short story “Old Joy” for a 2004 book of photography by Justine Kurland, and the script follows the story quite closely, aside from a few sly additions by Reichardt. The director includes the presence of Mark’s pregnant wife in the opening scenes, and again later in Mark’s calls home, suggesting the character’s domesticity. When Kurt asks Mark how he’s going to handle impending parenthood, Mark’s cagey reply signals his suppressed terror: “We’re stretched so thin with work, it’s almost impossible to imagine. But it’ll have to work itself out.” Reichardt also included her real-life dog, Lucy, as Mark’s other companion on the journey. Always scampering around the frame or discovering a large stick she can barely carry, Lucy remains oblivious to the strained friendship and, in her carefree way, renders everything onscreen almost comical by contrast.

Moving from the suburbs of Portland into an ocean of lush green mountains, Old Joy finds its characters escaping their modern landscape for a brief respite from their anxieties of the mind and body, but not always in equal measures. Kurt seems to have found peace with his shape and, fueled by the constant presence of marijuana, he shows no restraint when disrobing before his friend. Mark is more guarded, his mind active behind layers of protective shells—at first, he’s no more settled into Nature with Kurt than he is capable of meditating in his backyard. What comes next could be a scene of understated homoeroticism, or perhaps it shows Mark achieving a brief mind-body balance he never could with meditation. Kurt approaches from behind and places his hands on Mark’s shoulders for a massage. Mark resists at first, but Kurt settles him into it, and finally, Mark’s wedding-ringed hand relaxes into the warm water. However one interprets this loaded moment, its nature is fleeting. Mark will return home to his talk radio and domestic prison, whereas Kurt’s sense of unease feels accelerated in the final shots back in Portland, where he scurries on the streets like a coyote lost in the city.

Moving from the suburbs of Portland into an ocean of lush green mountains, Old Joy finds its characters escaping their modern landscape for a brief respite from their anxieties of the mind and body, but not always in equal measures. Kurt seems to have found peace with his shape and, fueled by the constant presence of marijuana, he shows no restraint when disrobing before his friend. Mark is more guarded, his mind active behind layers of protective shells—at first, he’s no more settled into Nature with Kurt than he is capable of meditating in his backyard. What comes next could be a scene of understated homoeroticism, or perhaps it shows Mark achieving a brief mind-body balance he never could with meditation. Kurt approaches from behind and places his hands on Mark’s shoulders for a massage. Mark resists at first, but Kurt settles him into it, and finally, Mark’s wedding-ringed hand relaxes into the warm water. However one interprets this loaded moment, its nature is fleeting. Mark will return home to his talk radio and domestic prison, whereas Kurt’s sense of unease feels accelerated in the final shots back in Portland, where he scurries on the streets like a coyote lost in the city.

Shooting on Super 16mm that was later transferred to 35mm, cinematographer Peter Sillen captures incredibly beautiful scenes that Reichardt, as editor of the picture, arranges in a rhythmic procession. One might take Old Joy’s structure for granted until the sequence at the hot springs, where Reichardt cuts between Kurt’s determined calm and Mark’s repelled expression with agitated energy. It’s evidence of Reichardt’s discerning skill and craft, her calibration of two attentive performances by London and Oldham, and the way this film lingers in mind long afterward. The moment, both in the narrative and form, has left a rift. If there was already an unresolvable tension between Mark and Kurt, it has been exposed in a way that promises to keep them apart. Old Joy refuses to bring their friendship into clarity, emphasizing the chasm between them, and to a greater extent, the divide between all individuals. It’s a film that continues to resonate in its prolonged feelings of solitude in an increasingly cynical world where it sometimes feels impossible to be seen or understood.

Bibliography:

Fusco, Katherine, and Nicole Seymour. Kelly Reichardt – Contemporary Film Directors. University of Illinois Press, 2017.

Hall, E. Dawn. ReFocus: The Films of Kelly Reichardt. Edinburgh University Press, 2018.

Halter, Ed. “Old Joy: Northwest Passages.” Criterion.com. 12 December 2019. https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/6728-old-joy-northwest-passages. Accessed 17 January 2020.

Rowin, Michael Joshua. “Old Joy.” Cinéaste, vol. 33, no. 1, 2006. https://www.cineaste.com/winter2006/old-joy-review. Accessed 18 January 2020.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review