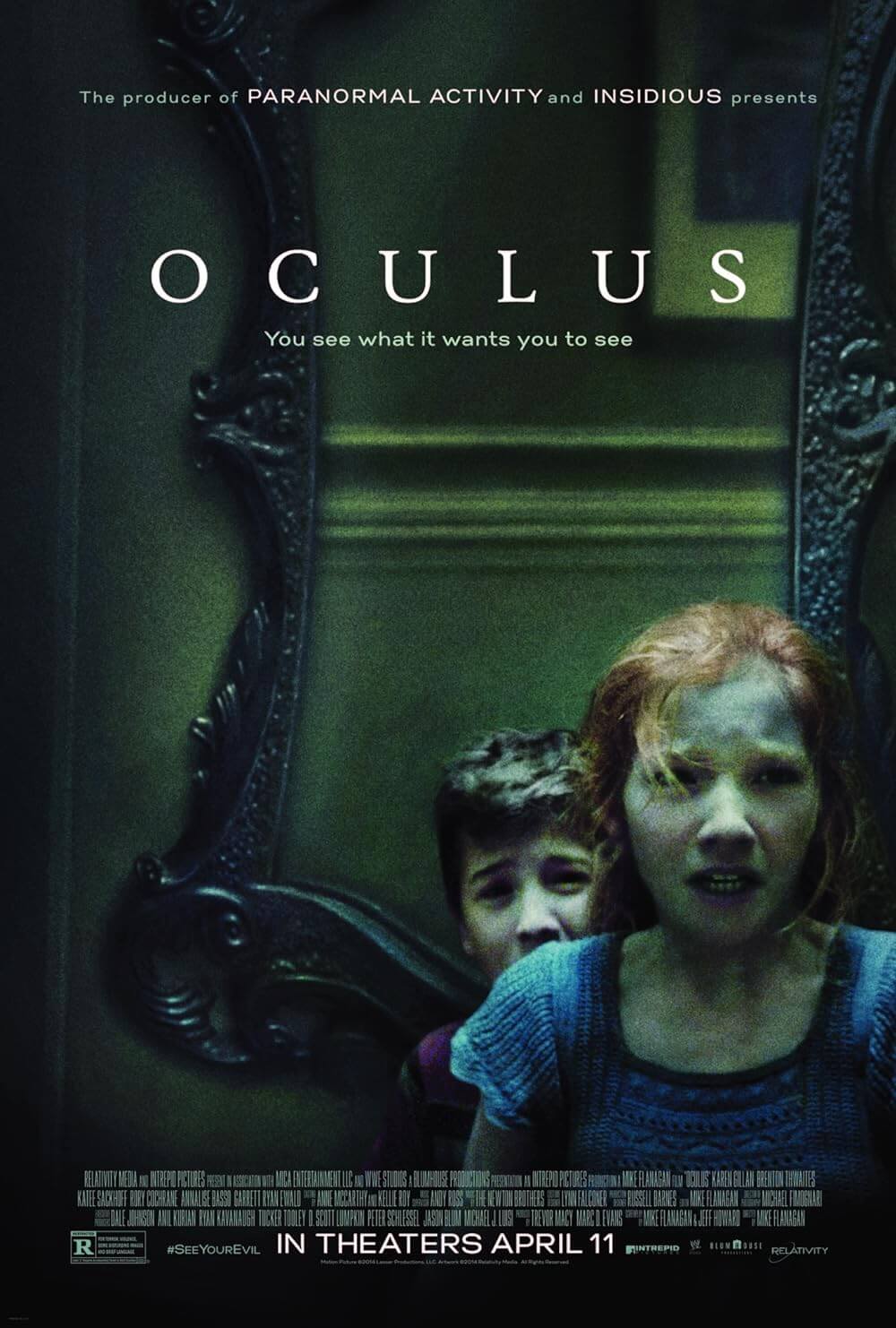

Oculus

By Brian Eggert |

In Oculus, director Mike Flanagan reflects the horror of family trauma and dysfunction. So many of the best horror films do, ranging from The Exorcist (1973) to The Babadook (2011) to Ari Aster’s work. Produced in part by Blumhouse, Flanagan’s film contains the usual smattering of jump scares and slinky wraiths to give viewers a case of the willies. But Flanagan’s treatment elevates the material, both in his use of mind games and emotional complexity. Since the release of Oculus in 2013, Flanagan’s name has been synonymous with horror that resonates in its confrontation of family dynamics and relationships. He adapted two Stephen King books into superb features and works of classical haunted house literature into masterful television, earning his reputation as a reliable source of exceptional horror. What makes his films different is the interest he shows in his characters’ psychological dimensions, even while he uses the occasional cliché—including jolts of music and the sudden appearance of something terrifying onscreen. He wields the standard equipment found in the horror filmmaker’s toolbox, but he uses them to craft something rather beautiful and quite devastating in the case of Oculus.

Flanagan and his co-writer Jeff Howard expanded their original 30-minute short into Oculus, the filmmaker’s second feature following his 2011 debut, Absentia. Their script carefully balances belief and skepticism, memory and experience, past and present. Flanagan weaves these themes into a narrative set mainly in a single location, recalling his structure to Netflix’s The Haunting of Hill House (2018). The story follows the 21-year-old Tim (Brenton Thwaites), who has just been released from a mental health facility after years of therapy for killing his father. His sister Kaylie (Karen Gillan), who is two years older, picks him up and quickly announces they must return to their childhood home to “keep our promise and kill it.” Confused, Tim doesn’t remember the promise nor what “it” is. His memories of 11 years earlier have changed, whereas Kaylie’s have only sharpened over time. Kaylie believes that once their family moved into their new house, their father Alan (Rory Cochrane), a temperamental software engineer, and mother Marie (Katee Sackoff) gradually went insane due to an evil mirror. The mirror fed on their parents and turned them against each other, driving Marie insane and Alan to violence. Their father eventually murdered their mother. He would have shot the kids next, except Tim shot him instead.

Flanagan embraces our inner skeptic with reasonable doubt. Influenced by his years of psychotherapy, Tim explains away Kaylie’s mirror hypothesis through psychology’s “fuzzy trace” theory, which proposes that our minds sometimes create false perceptions or associations to replace blanks or mask troublesome memories. “These problems are nothing to be ashamed of,” says Tim, adopting an after-school special tone. “They run in the family.” Tim remembers a very logical version of their past: his mentally ill dad was the man who tortured and killed their mother after she discovered him having an affair, leaving the boy no choice but to protect his sister. Those rational memories exist alongside what really happened, and Flanagan explores Tim’s mind pulling the curtain back. We see the events leading up to Alan’s death elegantly cross-cut with the events in the present. Oculus unfolds, then, across two timelines that, in their parallel trajectories, begin to overlap in creepy ways. Thanks to some supernatural wizardry, the adult Kaylie and Tim see younger versions of themselves (Annalise Basso, Garrett Ryan Ewald) in some manner of memory or ghostly projections. And they’re all headed toward a similarly tragic conclusion.

The film cleverly counters Tim’s psychological rationalizations with Kaylie’s pseudo-scientific method of proving that the mirror is an evil presence. Her research reveals that over 40 people have experienced horrific deaths around the mirror in the last 400 years. Each instance reports similar effects: plants wilt, pets disappear, and people go mad—they stop eating, die from hunger or thirst, or mutilate themselves and others. The intelligent script finds Kaylie preparing for their showdown by setting up an experiment to prove her theory: a network of cameras and fail-safes, including alarms every 45 and 60 minutes; a weighted anchor that will obliterate the mirror if Kaylie doesn’t reset a timer; her fiancé (James Lafferty) will call at the top of every hour to ensure she’s safe. All of this is a flashing warning sign to Tim. After getting released from the hospital, he sees Kaylie’s story as the sign of a diluted mind—until, of course, they witness proof of the mirror’s power.

The film cleverly counters Tim’s psychological rationalizations with Kaylie’s pseudo-scientific method of proving that the mirror is an evil presence. Her research reveals that over 40 people have experienced horrific deaths around the mirror in the last 400 years. Each instance reports similar effects: plants wilt, pets disappear, and people go mad—they stop eating, die from hunger or thirst, or mutilate themselves and others. The intelligent script finds Kaylie preparing for their showdown by setting up an experiment to prove her theory: a network of cameras and fail-safes, including alarms every 45 and 60 minutes; a weighted anchor that will obliterate the mirror if Kaylie doesn’t reset a timer; her fiancé (James Lafferty) will call at the top of every hour to ensure she’s safe. All of this is a flashing warning sign to Tim. After getting released from the hospital, he sees Kaylie’s story as the sign of a diluted mind—until, of course, they witness proof of the mirror’s power.

Flanagan makes several sharp choices in setting up his mirror concept. For starters, he doesn’t explain the mirror’s origins. The viewer never learns whether Satan carved the ornate Bavarian black cedar frame by hand or if it’s the work of medieval occultists. Not knowing makes it scarier and enhances the division between siblings. Regardless, Kaylie’s camera soon captures the mirror at work—a disturbing sequence that finds them experiencing one thing while something else entirely occurs on video shot by her cameras. The mirror causes them to lose themselves in flashbacks or hallucinations, especially when they try to destroy it or escape its influence. Kaylie’s plan includes regular breaks for food and water, ensuring the siblings will remain energized, which only welcomes the mirror to feed on them, thereby strengthening its projections of ghostly or false imagery. At one point, Kaylie bites into an apple and finds she has bitten into a lightbulb, leaving shards stuck in her mouth—but it’s all a disturbing hallucination. Yet, despite all the screentime devoted to their altered mental states, Oculus never feels like it’s dwelling on the past—there’s a decided forward thrust that builds to dual climaxes involving Tim and Kaylie as both children and adults.

The proceedings feel like Flanagan’s dry run for his 2019 adaptation of Stephen King’s Doctor Sleep, which hit bookshelves in 2013, the same year Oculus debuted at the Toronto Film Festival. Doctor Sleep found a traumatized Danny Torrence confronting his ghostly past by returning to the haunted Overlook Hotel, much like Kaylie and Tim’s return to the place of their childhood trauma. The scenes from their childhood, inside a house filled with an abusive and solitary father who has a secret relationship with evil spirits, vaguely recall those with Jack Nicholson in The Shining (1980)—or even those in Doctor Sleep’s recreated scenes featuring Henry Thomas as Jack. Cochrane even looks like those Jacks, especially after Alan becomes short-tempered and committed to appeasing the succubus who draws energy from him like a vampire. When Kaylie and Tim hide behind a bathroom door, on the other side of which one of their parents bangs their fists, we almost expect the possessed to announce, “Heeeere’s Johnny!” But they do not. And while Flanagan may have drawn from The Shining for inspiration, he mercifully avoids making direct references to those King works, regardless of their similarities.

As ever, Flanagan’s priority remains his characters’ dramatic integrity. His feature films and miniseries for Netflix, particularly The Haunting of Hill House, use horror to supply a stage for an expression of humanity. Flanagan never resorts to cheap thrills; even when making something like Ouija: Origin of Evil (2016), he gives the material its due consideration. The supernatural element aligns with the dramaturgy, whether it’s a ghost, vampire, or possessed mirror tormenting his characters. In the case of Oculus, he uses the haunted mirror as a symbolic device that reflects how adults look at themselves and realize they have become their parents and repeated their mistakes, despite knowing about them in advance. Kaylie seems driven to project her fears and anxieties onto the mirror to fanatical extremes, just as Marie fell into mental derangement after denying her failing marriage and husband’s infidelity. Kaylie’s identification with her mother leads to her downfall. Tim, too, seems fated to return to a mental facility after once again falling victim to the mirror’s schemes.

As ever, Flanagan’s priority remains his characters’ dramatic integrity. His feature films and miniseries for Netflix, particularly The Haunting of Hill House, use horror to supply a stage for an expression of humanity. Flanagan never resorts to cheap thrills; even when making something like Ouija: Origin of Evil (2016), he gives the material its due consideration. The supernatural element aligns with the dramaturgy, whether it’s a ghost, vampire, or possessed mirror tormenting his characters. In the case of Oculus, he uses the haunted mirror as a symbolic device that reflects how adults look at themselves and realize they have become their parents and repeated their mistakes, despite knowing about them in advance. Kaylie seems driven to project her fears and anxieties onto the mirror to fanatical extremes, just as Marie fell into mental derangement after denying her failing marriage and husband’s infidelity. Kaylie’s identification with her mother leads to her downfall. Tim, too, seems fated to return to a mental facility after once again falling victim to the mirror’s schemes.

Although it’s another of Blumhouse’s low-budget productions, Oculus, which earned upwards of $44 million on a reported $5 million budget, features convincing performances from the small cast—the child actors and parents, in particular. It’s also a handsome production with thoughtfully considered lighting and textures in an otherwise limited space. Flanagan and his regular cinematographer, Michael Fimognari, know how to shoot darkness without sacrificing visibility; the director is almost unparalleled in this respect, next to David Fincher or Gordon Willis. He also creates memorable spirits with subtle touches of makeup and lighting, such as the glowing eyes of victims consumed by the mirror (he used a similar trick to great effect on his 2021 miniseries, Midnight Mass). Most of all, Oculus doesn’t feel like another supernatural cheapie designed to earn a buck. Instead, it’s rooted in character, and it uses a persistent menace instead of shocks to unnerve the viewer. Not only does it signal the excellent work from Flanagan to come, but it remains among his best and scariest films.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review