Reader's Choice

Ocean’s Twelve

By Brian Eggert |

If Ocean’s Eleven (2001) represents a straight line to the heist of three Las Vegas casinos, the sequel zig-zags, detours, and dances through a randomized laser grid to arrive at its destination. Ocean’s Twelve (2004) is a breezier, laid-back affair, with less to prove and more freedom to explore, despite the life-or-death stakes. It’s proof the Ocean’s films adopt heist genre conventions in service of hangout movies, where the predominant agenda is to explore the friendships and working relationships among the characters. Soderbergh delivers his version of twisty European entertainment from the 1960s, evidenced by his occasional throwback aesthetic devices, along with his interest in locations and movie stars more than a plot. Unfortunately, Ocean’s Eleven’s slick and subversive theme about underdogs stealing from wealthy capitalist interests and corporate mobsters is a casualty of the sequel’s loose coolness and humor. But it’s an effortless sequel whose pleasures turn in a refreshingly different direction. Rather than involve the audience in planning a singular heist, Soderbergh and his starry cast make the viewer a participant—first, in the close dynamic of the cast onscreen, and second, as a spectator grifted by the world’s greatest thief.

After Ocean’s Eleven’s massive box-office take ($450 million worldwide), the sequel was inevitable, and talks began between producer Jerry Weintraub and Soderbergh about sequel ideas. Rather than make a carbon copy of the original, the director thought the sequel might involve Terry Benedict (Andy Garcia) tracking down the gang, requiring them to pull off several high-profile jobs to pay back what they stole. Soderbergh explained, “Unlike the first film, where you’re having fun watching them be successful and get a lot of things right, I thought it would be more fun if Twelve was the movie in which everything goes wrong from the get-go.” Then came George Nolfi with his unrelated script called Honor Among Thieves, about two professional thieves competing to determine who among them was the world’s best. Soderbergh recognized that Nolfi’s script matched the tone of Ocean’s Eleven and resolved to merge their ideas into the sequel, with Nolfi receiving screenwriter credit (refashioning an existing script into franchise material is a common Hollywood tactic). Throughout filming, many of Soderbergh’s ideas remained tangential asides, with several alternate takes and scenes left on the cutting room floor. Soderbergh’s desire for experimentation also allowed the cast to play within a framework. Yet, the sequel’s playfulness would become a problem for many of the original’s fans.

Soderbergh has overseen two trilogies, directing the Ocean’s trilogy and two of the three Magic Mike features (2015’s Magic Mike XXL went to Soderbergh’s longtime assistant director Gregory Jacobs). But Soderbergh’s sequels often receive scorn from critics and audiences who want more of the same, while Soderbergh seems determined to reinvent with each new entry. Just as many clamored for more stripping from Magic Mike’s Last Dance (2023) to match the lightheartedness ofMagic Mike XXL, many viewers balked at the lower-stakes affair of Ocean’s Twelve that resituated events from Las Vegas to several European countries, including Amsterdam, Rome, and Paris. Along with the meandering plot, the sequel’s “after-hours” demeanor frustrated critics such as Lisa Schwarzbaum, who, in her Entertainment Weekly review, decries its nonchalance as a result of actors wanting a laid-back working environment: “What’s on screen is lazy, second-rate, phoned-in—a heist in which it’s the audience whose pockets have been picked.” Other critics complained that the story was inconsequential and less engaging than the original’s, while the filmmakers seemed satisfied to leave the audience out of the loop.

Soderbergh has overseen two trilogies, directing the Ocean’s trilogy and two of the three Magic Mike features (2015’s Magic Mike XXL went to Soderbergh’s longtime assistant director Gregory Jacobs). But Soderbergh’s sequels often receive scorn from critics and audiences who want more of the same, while Soderbergh seems determined to reinvent with each new entry. Just as many clamored for more stripping from Magic Mike’s Last Dance (2023) to match the lightheartedness ofMagic Mike XXL, many viewers balked at the lower-stakes affair of Ocean’s Twelve that resituated events from Las Vegas to several European countries, including Amsterdam, Rome, and Paris. Along with the meandering plot, the sequel’s “after-hours” demeanor frustrated critics such as Lisa Schwarzbaum, who, in her Entertainment Weekly review, decries its nonchalance as a result of actors wanting a laid-back working environment: “What’s on screen is lazy, second-rate, phoned-in—a heist in which it’s the audience whose pockets have been picked.” Other critics complained that the story was inconsequential and less engaging than the original’s, while the filmmakers seemed satisfied to leave the audience out of the loop.

Like its predecessor, Ocean’s Twelve would rather spend its runtime with its characters and the stars playing them than expound on its elaborate plot. The film opens with Danny Ocean (George Clooney) settled into Connecticut-brand domestic drudgery with his hard-won wife, Tess (Julia Roberts). A stop at the bank to open a retirement account leaves him itchy with a desire to make a comeback. Then, as if on cue, Benedict arrives to confront Tess, declaring his intention to recover the millions stolen from his casinos by Ocean’s crew, with interest. Instead of Ocean getting the team back together, they’re assembled by Benedict and his enforcers, giving the audience a glimpse of how they chose to spend their riches: the acrobat Yen (Qin Shaobo) lives in a party house with models; Frank (Bernie Mac) runs a nail salon in New Jersey; Basher (Don Cheadle) struggles to become a London music producer; Linus (Matt Damon) continues to learn the craft in Boston, stricken with an inferiority complex given his father’s reputation in the underworld; the Malloy twins (Casey Affleck, Scott Caan) continue to bicker in Utah; techie Livingston (Eddie Jemison) tries his hand at being a stand-up illusionist in New Orleans; Reuben (Elliot Gould) never left Vegas; Saul (Carl Reiner) has retired to the East Hamptons; and Rusty (Brad Pitt) micromanages his struggling hotel business.

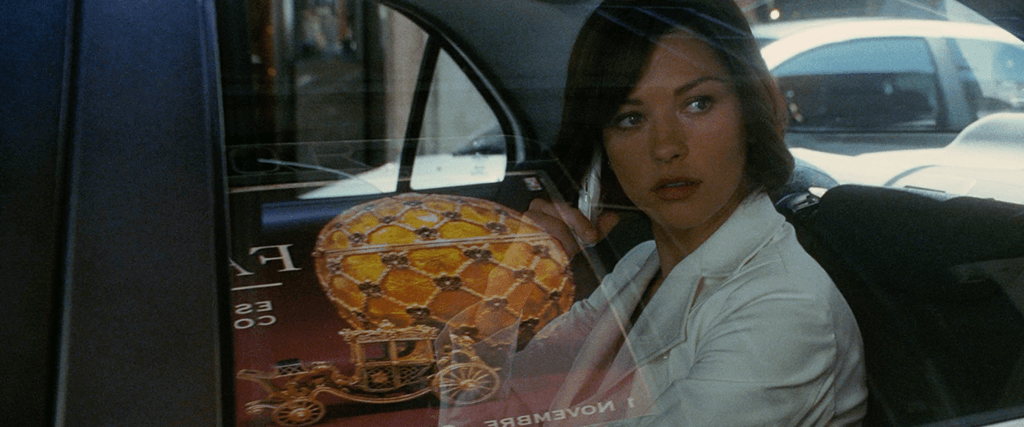

Benedict gives them an ultimatum: pay what you owe, or else. Burned in the US, Danny and company—minus Saul, who’s content to die a rich man—head to Europe to steal $97 million, which, in addition to their remaining bankrolls, will satisfy Benedict. Although Linus’ hilariously adolescent sheepishness finds him asking for a more prominent role this time, the story centers on Rusty in a thread recalling the cop-and-thief romance in Soderbergh’s superb Out of Sight (1998). A flashback set in Rome three-and-a-half years ago establishes Rusty’s past affair with Isabelle Lahiri (Catherine Zeta-Jones), an Interpol agent who specializes in catching professional thieves. When Rusty realizes she’s on his trail, he bolts. Now, in Europe, Lahiri and Danny’s crew share stories about legendary criminals, none more so than the mysterious, never-seen, long-retired Gaspar LeMarc. In an underworld of thieves akin to the hitman collective in the John Wick series, master thieves go by multiple aliases, and Lahiri’s enigmatic birth father was one of them. Another is Baron François Toulour (Vincent Cassel), a rich, bored, and talented playboy who goes by The Night Fox. Desperate to prove that he’s better than Ocean’s Eleven, Toulour sold them out to Benedict, if only to force Ocean into a competition for the title of “world’s greatest thief.”

If the earlier film adhered to the moral stance that stealing from the rich was acceptable, the sequel establishes a code among thieves, whose primary rule is not to inform on a fellow thief. But that’s merely the impetus for an escapist Hollywood movie, where most of the plot is a clever misdirection. The team wastes time and resources on an Amsterdam job to lift the first stock certificate, only to be undercut by The Night Fox. After ratting on them to Benedict to get Ocean’s attention, Toulour bets with Ocean that he can steal the Russian Imperial Coronation Fabergé Egg before Ocean’s team. Should he lose, Toulour will pay their debts to Benedict. However, as we learn much later, Ocean and company steal the Fabergé Egg long before Toulour realizes, rendering their scheme(s) in the interim to be mere distractions. The pleasure of Ocean’s Twelve isn’t about watching the crew complete heists. It’s about watching this cast share scenes in stunning locales, while their characters bungle each job in a hilarious inversion of the 2001 film.

If the earlier film adhered to the moral stance that stealing from the rich was acceptable, the sequel establishes a code among thieves, whose primary rule is not to inform on a fellow thief. But that’s merely the impetus for an escapist Hollywood movie, where most of the plot is a clever misdirection. The team wastes time and resources on an Amsterdam job to lift the first stock certificate, only to be undercut by The Night Fox. After ratting on them to Benedict to get Ocean’s attention, Toulour bets with Ocean that he can steal the Russian Imperial Coronation Fabergé Egg before Ocean’s team. Should he lose, Toulour will pay their debts to Benedict. However, as we learn much later, Ocean and company steal the Fabergé Egg long before Toulour realizes, rendering their scheme(s) in the interim to be mere distractions. The pleasure of Ocean’s Twelve isn’t about watching the crew complete heists. It’s about watching this cast share scenes in stunning locales, while their characters bungle each job in a hilarious inversion of the 2001 film.

Soderbergh’s film contains all the glamour of mid-century Hollywood Euro-ventures, most notably Alfred Hitchcock’s To Catch a Thief (1955)—another film wherein the plot is useless compared to the riches offered by its stars and lavish backdrops. Scenes in Amsterdam and Lake Como feel like throwbacks to an era where movies doubled as widescreen travelogues in Technicolor. In keeping with the sequel’s European flair, Soderbergh deploys several visual techniques developed by European auteurs in the 1960s, some of which remain characteristic of his work. The jump cuts and onscreen titles recall early François Truffaut; the code among thieves brings to mind Jean-Pierre Melville’s cool crime cinema; and the long zooms, along with David Holmes’ propulsive score that occasionally reaches Ennio Morricone’s romantic heights, evoke Italian films of the era. But Ocean’s Twelve isn’t an empty nostalgia=fest; Soderbergh offers memorable modern and postmodern flourishes as well.

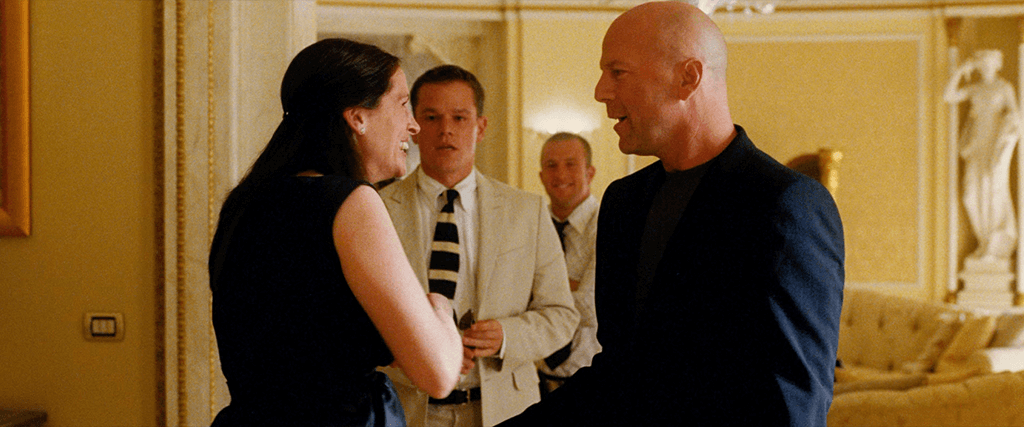

All the razzle-dazzle and glamor onscreen becomes a masterful sleight-of-hand, distracting the viewer with elaborate set pieces that amount to nothing—aside from an entertaining movie, the value of which should not be dismissed. But this is a stroke of genius rather than laziness. When Ocean’s crew spends days figuring out how to lift an entire building by two inches, only to come away empty-handed, it supplies an apt metaphor for the film’s story structure and ultimate purpose—a delightful diversion. Similarly, an intricate scheme involving Eddie Izzard and a holographic replica of the Fabergé Egg goes south when Isabelle arrests most of the team, leaving Linus and Basher to concoct a self-reflexive plan, requiring Tess to join them in Europe and play her celebrity look-alike—Julia Roberts. This self-referential thread seemed to be the breaking point for some critics, who balked at the film embracing itself as a compendium of Hollywood stars. Soderbergh’s pairing of Roberts and later Bruce Willis (as himself) doubles as a nod back to Robert Altman’s The Player (1992), in which Roberts and Willis play themselves, performing in a mock sell-out movie called Habeus Corpus.

The best of these distractions is The Night Fox’s rhythmic dance through a moving laser sensor field to a hypnotic beat by French rap group La Caution (an instrumental version of their track “Thé à la Menthe”), toward a Fabergé Egg that proves to be a convincing decoy. Cassel danced himself, being a trained acrobat and versed in Capoeira, an Afro-Brazilian tradition that combines martial arts and dance. Though the lasers may have been added after the fact (lasers are typically not visible unless illuminated by something in the air, such as fog, smoke, or dust, none of which are apparent here), Cassel’s agility is the scene’s special effect. Even with such displays, Soderberg deflates typically masculine displays of thieving bravado—The Night Fox is the villain, after all. For every outlandish scheme concocted and performed by men, there’s a grounded woman critical of these boys’ antics: Tess remains disapproving when she’s drawn into the scheme; Isabelle works to catch the thieves, while allusions to Isabelle’s mother suggest she wanted nothing to do with Isabelle’s thief-father; Linus’ mother (Cherry Jones) rescues the team from peril in a mater ex machina, offering mild censures of her novice son. Ocean’s Twelve at once embraces its casual boy’s club quality while simultaneously critiquing it from a woman’s perspective. But Soderbergh’s treatment never overemphasizes the rather stereotypical gender dynamics, and by the end, everyone feels part of the same thieving collective that their initial conflicts hardly matter.

The best of these distractions is The Night Fox’s rhythmic dance through a moving laser sensor field to a hypnotic beat by French rap group La Caution (an instrumental version of their track “Thé à la Menthe”), toward a Fabergé Egg that proves to be a convincing decoy. Cassel danced himself, being a trained acrobat and versed in Capoeira, an Afro-Brazilian tradition that combines martial arts and dance. Though the lasers may have been added after the fact (lasers are typically not visible unless illuminated by something in the air, such as fog, smoke, or dust, none of which are apparent here), Cassel’s agility is the scene’s special effect. Even with such displays, Soderberg deflates typically masculine displays of thieving bravado—The Night Fox is the villain, after all. For every outlandish scheme concocted and performed by men, there’s a grounded woman critical of these boys’ antics: Tess remains disapproving when she’s drawn into the scheme; Isabelle works to catch the thieves, while allusions to Isabelle’s mother suggest she wanted nothing to do with Isabelle’s thief-father; Linus’ mother (Cherry Jones) rescues the team from peril in a mater ex machina, offering mild censures of her novice son. Ocean’s Twelve at once embraces its casual boy’s club quality while simultaneously critiquing it from a woman’s perspective. But Soderbergh’s treatment never overemphasizes the rather stereotypical gender dynamics, and by the end, everyone feels part of the same thieving collective that their initial conflicts hardly matter.

After all, how can you stay mad at Brad Pitt or George Clooney? How could Pitt’s character hold it against Zeta-Jones’ cop for arresting the lot of them? Everyone’s so damn good-looking, they just have to get along. Even while the sequel once again saturates the viewer in its coolness—not only from the cast and lighthearted tone but from Soderbergh’s expert direction—it also deflates Ocean’s crew. Their schemes land them in trouble, and though Ocean’s forethought saves them, revealed in a last-minute con job, it’s only by a narrow margin. Deceptively lighthearted and meandering, the film uses the audience’s goodwill toward these characters in a sly presentation that embraces and critiques, using the spectator as a mark. When detractors fuss that Ocean’s Twelve doesn’t have the same sparkle Ocean’s Eleven did, there’s no argument against them; it has a wholly different type of shine. Too often in sequels, we see replicas of the original, simply painted over to give the illusion of superficial differences. Ocean’s Twelve resolves to be more than a convincing decoy or even a holographic copy. It’s another score altogether.

(Note: This review was originally suggested and posted to Patreon on June 22, 2023.)

Bibliography:

Baker, Aaron. Steven Soderbergh. Contemporary Film Directors. University of Illinois Press, 2011.

DeWaard, Andrew and R. Colin Tait. The Cinema of Steven Soderbergh: Indie Sex, Corporate Lies, and Digital Videotape. Wallflower Press, 2013.

Gallager, Mark. Another Steven Soderbergh Experience: Authorship and Contemporary Hollywood. University of Texas Press, 2013.

Kaufman, Anthony. Steven Soderbergh Interviews. Jackson University Press, 2002.

Palmer, R. Barton and Steven M. Sanders. The Philosophy of Steven Soderbergh. The University Press of Kentucky, 2011.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review