Reader's Choice

Ocean’s Thirteen

By Brian Eggert |

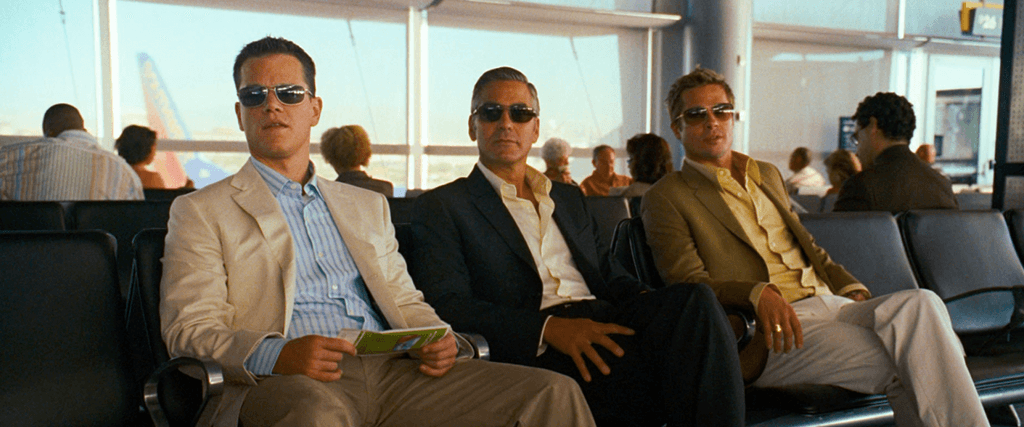

Ocean’s Thirteen is a low-key pleasure that rests on the charm of its leading men and the deceptively casual style of its director, Steven Soderbergh. George Clooney, Brad Pitt, Matt Damon, and the rest return for the 2007 sequel, which attempts to course correct after the mixed response to the playfully meta Ocean’s Twelve (2004). Back in Las Vegas, the film continues to romanticize the 1960s, when Frank Sinatra still reigned as Chairman of the Board, and the smaller hotels seemed bigger somehow. However seedy the Vegas of yesteryear might seem by comparison, everyone had a code back then. Clooney’s Daniel Ocean and company serve as guardians of that code; together, they’re the last vestige of old-school class in a world overtaken by crass corporations and ambitious thieves willing to undercut one another for bragging rights. They occasionally stop to reflect on the past, dreaming of and recalling more idyllic days from their youth. Whatever downfalls they might conveniently overlook, there’s plenty to enjoy about the present: the good-looking stars, the casual plotting, and the silly asides. But it’s not so much about the mission as Soderbergh’s style that carries us along from moment to moment. No matter how implausible, he makes it all look so cool.

The gang returns to Vegas to settle a score with Willie Bank (Pacino), a casino mogul so greedy he makes Terry Benedict (Andy Garcia), the personification of corporate interests from Ocean’s Eleven (2001), look like a regional credit union with two branch offices. Recalling Donald Trump behind his spray-tan-orange complexion and gaudy affinity for gold (glasses, flatware, etc.), Bank is not only a ruthless capitalist but also has no code. He shows no remorse when his double-cross of Ocean’s financier friend, Reuben (Elliot Gould), prompts a heart attack. Bank should know better, according to Ocean, because he shook Sinatra’s hand, and there’s a code among guys who shook hands with Ol’ Blue Eyes. Bank fails to atone properly, so Ocean’s band of merry men assemble to steal from the rich and give to the… somewhat less rich. The crew plans to hit Bank’s new hotel-casino called The Bank because, like Trump, Bank needs his name on everything. The place has been designed to accommodate “whales”—ultra-rich gamblers who like to bet big and lose millions. Rather than stealing from Bank, Ocean’s crew plans to rig the games on the casino’s grand opening and leave him bankrupt, allowing the whales to take home even more money than they started with and putting Bank out of business.

Ocean’s Thirteen plays it fast and loose with ethics among thieves. The screenplay by Rounders (1998) scribes Brian Koppelman and David Levien is a revenge story. But no one’s out for blood—and when someone (Vincent Cassel, returning as The Night Fox) brings a gun to the proceedings, there’s a sense that he’s broken the most important rule of all. Instead, they’re out to teach a lesson. After all, Ocean’s crew seems to be living comfortably enough, so they can afford to spend six months planning and financing a project to avenge Reuben, who remains bedridden until the big night. Eventually, they drain their finances and must ask Benedict to fund their operation. At least Benedict has enough sense to hire someone to curate his casino’s art museum. Bank has no tastes; he slaps a faux Asian aesthetic onto his hotels, employs “models who serve” so he can berate their appearance, and covets the hotel industry’s Five Diamond Award—a $50 million necklace Bank has won several times before. He’s supported by Abigail Sponder (Ellen Barkin, reteaming with Pacino after their 1989 feature, Sea of Love), a beleaguered personal assistant.

Calling Ocean’s Thirteen a heist movie would be a mistake. Besting Bank means carrying out a series of small cons, rigging games, and outsmarting a never-before-used security system that can sense dishonesty by monitoring a player’s vitals. Garcia and Eddie Izzard’s tech whiz Roman join Ocean’s usual crew: Don Cheadle, Casey Affleck, Scott Caan, Bernie Mac, Carl Reiner, Eddie Jemison, and Qin Shaobo. The entire cast is back apart from Julia Roberts and Catherine Zeta-Jones, who reportedly wanted more prominent roles, but then, everyone feels secondary to Clooney and Pitt. “It’s not their fight,” Ocean resolves. Yet, an ongoing dialogue between Ocean and Rusty pokes fun at how they’ve become uneasily trapped in domesticated adult lives. A story about Rusty leaving a pancake on the kitchen floor overnight after a lover’s spat colors him as hilariously childish. Indeed, they’ve been unsuccessful at asserting themselves at home, prompting this rebellion back to the boys’ clubhouse that practically has a “No Girls Allowed” sign on the door. Like a thread from Ocean’s Twelve (2004), Soderbergh is willing to show that the women, even absent ones, view his ultra-cool cast as immature man-children.

Calling Ocean’s Thirteen a heist movie would be a mistake. Besting Bank means carrying out a series of small cons, rigging games, and outsmarting a never-before-used security system that can sense dishonesty by monitoring a player’s vitals. Garcia and Eddie Izzard’s tech whiz Roman join Ocean’s usual crew: Don Cheadle, Casey Affleck, Scott Caan, Bernie Mac, Carl Reiner, Eddie Jemison, and Qin Shaobo. The entire cast is back apart from Julia Roberts and Catherine Zeta-Jones, who reportedly wanted more prominent roles, but then, everyone feels secondary to Clooney and Pitt. “It’s not their fight,” Ocean resolves. Yet, an ongoing dialogue between Ocean and Rusty pokes fun at how they’ve become uneasily trapped in domesticated adult lives. A story about Rusty leaving a pancake on the kitchen floor overnight after a lover’s spat colors him as hilariously childish. Indeed, they’ve been unsuccessful at asserting themselves at home, prompting this rebellion back to the boys’ clubhouse that practically has a “No Girls Allowed” sign on the door. Like a thread from Ocean’s Twelve (2004), Soderbergh is willing to show that the women, even absent ones, view his ultra-cool cast as immature man-children.

The humor is a bit goofier this time around, making Ocean’s Thirteen the most purely comic of the bunch. Clooney, Pitt, and Affleck wear fake mustaches for absurdist disguises. A subplot involves Damon’s Linus donning a fake aquiline nose to seduce Barkin’s character with the help of a pheromone that crawls up her nose like the scent of a beef roast compels a cartoon dog. That leads to the series finally introducing Linus’ much-discussed father, played by the hilarious Bob Einstein, an FBI agent moonlighting as a con man (or maybe the other way around). Most of the side characters have little to do. Mac, Jemison, and Qin feel peripheral. But Reiner once again shines, pretending to be a proper British hotel critic to distract Bank from the real critic (David Paymer)—an unfortunate man put through the wringer by Ocean’s crew (bad smells, booked restaurants, food poisoning, and bedbugs). But, keeping to their code, they arrange for him to win big.

Although less self-referential than its predecessor, the sequel finds Clooney and Pitt sharing onscreen barbs about their off-screen lives. Jokes about the weight Clooney put on for Syriana (2005) and Pitt’s many adopted children with then-wife Angelina Jolie seem like had-to-have-been-there moments today, as do nods to their teary-eyed reactions to Oprah Winfrey’s “Favorite Things” episodes. But it’s not all chummy jokes and lighthearted asides. Ocean’s Thirteen also offers at least one subplot that’s the funniest and most sociopolitical sequence in the film: To manipulate dice at their source, Virgil (Affleck) works undercover in a Mexico plant. After experiencing the poor conditions, he incites the local workforce to demand more pay and air conditioning, prompting a worker’s strike. His brother from Utah (Caan) later arrives to restore the situation but quickly joins them, resulting in revolution and Molotov cocktails. In the end, the workers demand $36,000—not per person but in total, underscoring how little these Mexican workers live on and putting the situation at The Bank into perspective.

Despite the film’s $85 million budget and its roster of expensive stars (all taking salary cuts to make the budget manageable), Ocean’s Thirteen doesn’t feel like a big, empty Hollywood product. Soderbergh’s casual, personal touch gives it humanity. His distinct stylistic flourishes—from saturating The Bank in red hues to his New Wave-brand of editing to deploying almost self-consciously artificial digital grain in casino scenes—make it the work of an individual. Serving as cinematographer under his pseudonym Peter Andrews, the director’s slick camerawork and the smartly timed cuts by his frequent editor Stephen Mirrione result in “a Steven Soderbergh film” just as much as his smaller or more idiosyncratic pictures from the period. The film has a handcrafted quality to the filmmaking that supplies an alternative to the corporate, committee-made Hollywood sequels that dominated the multiplex then and now. By comparison, it feels like a large-scale indie—an accessible piece of entertainment made under the formal particulars of art.

Despite the film’s $85 million budget and its roster of expensive stars (all taking salary cuts to make the budget manageable), Ocean’s Thirteen doesn’t feel like a big, empty Hollywood product. Soderbergh’s casual, personal touch gives it humanity. His distinct stylistic flourishes—from saturating The Bank in red hues to his New Wave-brand of editing to deploying almost self-consciously artificial digital grain in casino scenes—make it the work of an individual. Serving as cinematographer under his pseudonym Peter Andrews, the director’s slick camerawork and the smartly timed cuts by his frequent editor Stephen Mirrione result in “a Steven Soderbergh film” just as much as his smaller or more idiosyncratic pictures from the period. The film has a handcrafted quality to the filmmaking that supplies an alternative to the corporate, committee-made Hollywood sequels that dominated the multiplex then and now. By comparison, it feels like a large-scale indie—an accessible piece of entertainment made under the formal particulars of art.

Maybe that’s what endears me to Soderbergh so much. No matter how big his budget or how far-reaching his scope, it always feels like he’s behind the camera, creating goodwill among his cast and guiding the proceedings with his particular aesthetic. With Ocean’s Thirteen, Soderbergh rounds out a trilogy of high-priced, high-earning hangout movies where the audience feels included among some of Hollywood’s biggest stars. Less than ten years later, Ocean’s 8 (2018) would attempt to replicate the trilogy’s success with an all-female cast—a worthy concept, except for the missing component: Soderbergh. Hard as he tried, director Gary Ross couldn’t duplicate Soderbergh’s smooth, confident, and personal style. Soderbergh better copied his formula in 2017’s Logan Lucky, a similar heist ensemble. To be sure, it’s not about the cast, the casual humor, the Oprah references, or the twisty plotting; it’s about the attitude with which Soderbergh imbues the material. His status as a distinct artist harmonizes with his sensibilities as an entertainer, making even something as accessible, negligible, and fun as Ocean’s Thirteen feel apart from the usual Hollywood product.

(Note: This review was originally suggested and posted to Patreon on July 5, 2023.)

Bibliography:

Baker, Aaron. Steven Soderbergh. Contemporary Film Directors. University of Illinois Press, 2011.

DeWaard, Andrew and R. Colin Tait. The Cinema of Steven Soderbergh: Indie Sex, Corporate Lies, and Digital Videotape. Wallflower Press, 2013.

Gallager, Mark. Another Steven Soderbergh Experience: Authorship and Contemporary Hollywood. University of Texas Press, 2013.

Kaufman, Anthony. Steven Soderbergh Interviews. Jackson University Press, 2002.

Palmer, R. Barton and Steven M. Sanders. The Philosophy of Steven Soderbergh. The University Press of Kentucky, 2011.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review