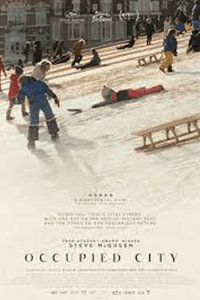

Occupied City

By Brian Eggert |

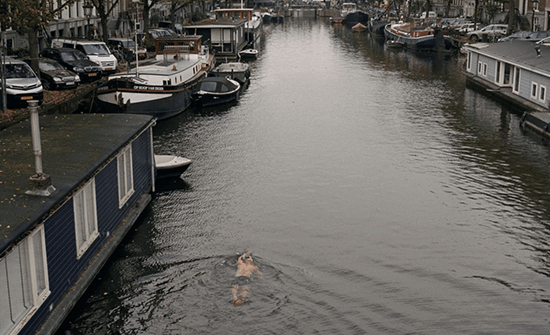

With its sobering subject matter and conceptual presentation, Steve McQueen’s Occupied City is unique among documentaries about World War II. The film creates dual portraits, visiting 130 locations around present-day Amsterdam and contrasting them with stories about the Nazi occupation that started in 1940. Streetlights were shut off. Weather reports became top secret. The ten-percent Jewish population was effectively banned from public life, while the National Socialist Movement in the Netherlands emerged. Within two years, the Nazis began deporting Jews to ghettos and, from there, to concentration camps. But rather than still photographs, archival footage, or even expert testimony to evoke this history, McQueen surveys today’s Amsterdam enduring lockdowns from COVID-19. Narrated by Melanie Hyams in a flat voiceover that contains nary a flicker of personality, the four-hour-and-twenty-two-minute feature, broken up by a fifteen-minute intermission, juxtaposes the visual present and an aural representation of the past to haunting effect, prompting the mind’s eye to fill in the space between them.

McQueen was inspired—or “informed,” to use the film’s parlance—by Dutch author Bianca Stigter’s 2019 book, Atlas of an Occupied City (Amsterdam 1940-1945). Her massive tome, which took over a decade to assemble, guides the reader through the city, uncovering one horrific event after another that occurred on Amsterdam’s city streets, in its buildings, and at its landmarks. More often than not, the locations bear the history of fascist oppression during the Nazi occupation; other places contain stories of resistance fighters. A journalist, writer, and documentary maker, Stigter has spent much of her career confronting this history. Her 69-minute documentary from 2021, Three Minutes: A Lengthening, explores ultra-rare home movie footage from the Polish village of Nasielsk, captured in 1938, not long before nearly half of its population was rounded up. McQueen, British, is Stigter’s husband, and they live together in the Netherlands. Stigter serves as producer on Occupied City.

Given its length, it’s worth wondering how viewers might consume this feature. Originally, McQueen had considered turning the project into an installation in a modern art museum, allowing spectators to enter the display and wander out when the moment presented itself. McQueen’s documentary, which A24 debuted on Christmas Day, hasn’t played at multiplexes, and, given the dearth of arthouse theaters these days, it’s not likely to play in many smaller theaters. Spectators may find Occupied City at home, though, given streaming viewing habits, attention spans may stray when confronted with the repetitive structure McQueen employs. It will be a slog and challenging to finish for impatient viewers, while the almost hypnotic approach will feel immersive for the more patient and discerning. I admit to falling somewhere in the middle, having felt engaged throughout yet undeniably restless about the runtime and unvaried presentation.

During the first hour, I found myself wondering whether this was an anti-lockdown feature meant to equate the Nazi occupation with the restrictions put into place during the pandemic. McQueen and Stigter have been careful not to discuss their audiovisual juxtapositions and where they stand on the lockdowns. Their concern is “illuminating” the past, and leaving the contemporary commentary up to the viewer. These thoughts, which nagged at me for the first hour, soon met with McQueen’s unmistakable inclusions. Seeing modern-day Dutch citizens exist in relative freedom—playing music and video games in their homes; visiting public parks; shopping in grocery stores; generally not looking oppressed at all—clashes with Hyams’ account of Jews in hiding, people getting dragged from their homes, violence in the streets, or the Dutch famine known as Hongerwinter (hunger winter) that left thousands dead from starvation. Although the Dutch authorities break up a lockdown protest in riot gear and use crowd dispersal tactics, the comparison suggests that the Dutch people have had it far worse, and perhaps, before locals begin comparing pandemic protocols to Nazi oppression, some historical perspective is needed.

During the first hour, I found myself wondering whether this was an anti-lockdown feature meant to equate the Nazi occupation with the restrictions put into place during the pandemic. McQueen and Stigter have been careful not to discuss their audiovisual juxtapositions and where they stand on the lockdowns. Their concern is “illuminating” the past, and leaving the contemporary commentary up to the viewer. These thoughts, which nagged at me for the first hour, soon met with McQueen’s unmistakable inclusions. Seeing modern-day Dutch citizens exist in relative freedom—playing music and video games in their homes; visiting public parks; shopping in grocery stores; generally not looking oppressed at all—clashes with Hyams’ account of Jews in hiding, people getting dragged from their homes, violence in the streets, or the Dutch famine known as Hongerwinter (hunger winter) that left thousands dead from starvation. Although the Dutch authorities break up a lockdown protest in riot gear and use crowd dispersal tactics, the comparison suggests that the Dutch people have had it far worse, and perhaps, before locals begin comparing pandemic protocols to Nazi oppression, some historical perspective is needed.

Each location captured by cinematographer Lennert Hillege’s crisp visuals has a story—a past and a present. But when McQueen combines them, they feel vitally unresolved. For instance, there’s a tension inside of what is a school today that once served as headquarters for the secret police. A similar tension inhabits Amsterdam’s Royal Concertgebouw, where the names of Jewish composers were hidden from view by the Nazis. Everywhere modern-day Dutch citizens live, walk, shop, and protest, citizens from the past experienced appalling persecution and crimes against humanity. Although it’s impossible to cover every story from this era, McQueen and editor Xander Nijsten give each account equal attention, regardless of its historical interest or familiarity. Note how McQueen doesn’t dwell on Anne Frank, whose diary became one of the twentieth century’s most potent and human documents of the Holocaust. She is referenced a few times, but her story, explored in other films with far more dimension, is part of the larger conversation. Nothing as expansive can be easily summarized by one example or even 130.

Occupied City is a meditation, and to achieve the intended contemplative response from the audience, the runtime feels justified. It has to be overwhelming and not easily contained within the usual two-hours-or-less documentary format. It cannot be streamlined for easier consumption because neither history nor the Holocaust—nor even the present—can be so conveniently summed up. Like Claude Lanzmann’s nine-and-a-half-hour Shoah (1985), the runtime isn’t intended to cover everything; instead, it goes to extreme lengths to demonstrate that these accounts have no end and their scars are immeasurable. However, Lanzmann’s picture feels more accessible, despite being more than twice as long, because of its presentational variety and clearer conceit. McQueen’s instructive film requires much from the viewer in its repetitive tone and execution, both intellectually and emotionally. But its cumulative power is overwhelming, while its questions about then and now remain.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review