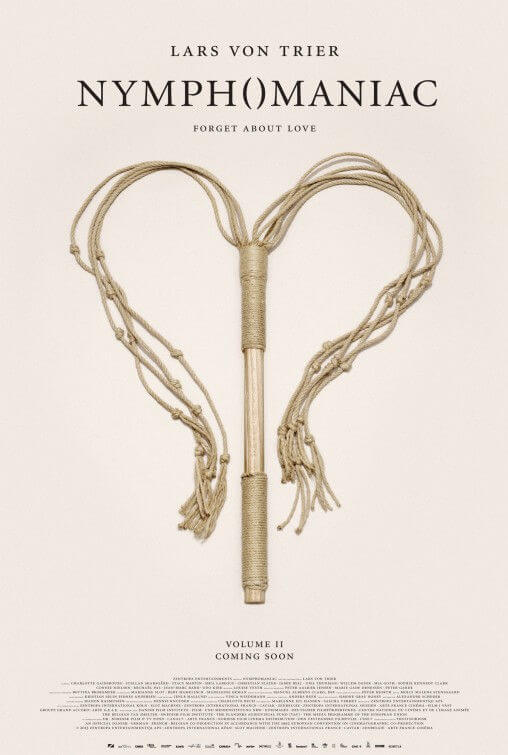

Nymphomaniac: Vol. 2

By Brian Eggert |

Freud once remarked, “The great question that has never been answered, and which I have not yet been able to answer, despite my thirty years of research into the feminine soul, is ‘What does a woman want?'” However problematic this line of investigation may be on its own from a feminist perspective, one imagines that Lars von Trier identified with Freud while making Nymphomaniac, his sexual odyssey into a troubled woman’s prolific sex life. What was originally released in Denmark as a five-hour sexcapade was abridged and halved by producer Louise Vesth and U.S. distributor at Magnolia. Receiving separate releases a month apart, Nymphomaniac Vol. 1 and Vol. 2 arrive as two-hour arthouse films, unrated and left to adventurous audiences ready to descend into depressive lows—as previously explored by the Danish filmmaker in the first two entries of his “depression trilogy,” Antichrist (2009) and Melancholia (2011).

From Breaking the Waves (1996) to Dancer in the Dark (2000) to Dogville (2004), von Trier regularly settles on female protagonists, often putting his female leads through the wringer in the trials they must endure. Few actresses have had to suffer through more under von Trier’s direction than Charlotte Gainsbourg, the performer who (via makeup effects, of course) chopped off her clitoris with scissors in Antichrist and, taking center stage in Nymphomaniac Vol. 2, her character undergoes a series of pronounced humiliations. Yes, the second chapter in von Trier’s exploration of sex and loneliness delves into even darker territory the viewer cannot deny, unlike the sense of antiseptic sexual discovery present throughout the first half. Vol. 1 left us with something of a cliffhanger, as sex-obsessed Joe (Gainsbourg), now a mother and coupled with her lifelong inamorato Jerome (Shia LaBeouf), has lost her ability to orgasm. Unable to keep up with her demands, Jerome suggests she hunt for fulfillment elsewhere, and her search leads her on a path of self-destruction.

In her Vol. 2 descent, Joe’s experimentations reach a level of severity not seen in Vol. 1, and it’s evident von Trier exploits this less for dramatic effect than to challenge his audience with the outrageousness of it all. Consider a scene in which Joe meets two black men in a cheap hotel and, as they argue about who gets which position in their three-way, their visibly erect members in the foreground frame Joe seated on the bed in the background. Such a shot means to provoke a response far removed from the dramatic pulse of the film, as does the extended interlude between Joe and an S&M guru (Jamie Bell), who refers to Joe as “Fido”, and whose chillingly unemotional approach to his work is brutal and disturbing. In another chapter, Joe takes work from an underground debt collector (Willem Dafoe) whose method of recovery involves sexual humiliation; this chapter is particularly challenging as Joe finds grounds to sympathize with a debtor who has a taste for pedophilia. Working for Dafoe’s character, Joe also develops a relationship with a teenage girl (Mia Goth) who’s both a lover and daughter-figure.

Structured like its predecessor, Vol. 2 unfolds largely in flashbacks told by the melancholic Joe, who, having been rescued by a Good Samaritan, Seligman (Stellan Skarsgård), relays her story by looking around Seligman’s apartment and naming each chapter after various observed objects (not unlike The Usual Suspects, although there’s no twist ending here). Seligman calls himself “asexual” and therefore posits himself as the perfect objective evaluator of Joe’s character, which in her view is irredeemable. He interrupts Joe’s story from time to time, questioning the plausibility of her tale, or comparing events in her life to Christian symbolism, Edgar Allan Poe, and Roman history. The best moments of Vol. 1 were when Joe’s story paused for a hearty debate about an intellectual point with Seligman, but there are fewer of those moments in Vol. 2. And though he maintains, “There’s nothing sexual about me,” Seligman’s virginal perspective is also that of a fascinated voyeur. In the final scene, von Trier spoils any emotional goodwill between the two characters (and between the film and his audience) when, uncharacteristically, Seligman attempts to take advantage of Joe in her sleep.

For many viewers, myself included, the final scene of Nymphomaniac Vol. 2 will be the last straw, punctuated with a decidedly silly, if not infuriatingly stupid outcome played out in audio form on a black screen. Far too much of Vol. 2 feels like an endurance test concocted by von Trier, wherein a deeply affecting drama about one woman’s despair is undone by the director’s desire to shock his audience. And while the film’s depictions of sadomasochism, vaginal bleeding, onscreen urination, and genital close-ups may be extremely graphic for arthouse film standards, audiences can read about worse in the pages of the Marquis de Sade or Henry Miller; in other words, von Trier isn’t breaking any new ground. This strain of confrontational filmmaking is constantly at war with, but never wholly counteracted by, Nymphomaniac‘s overall emotional foundation, which has a surprising impact. But unlike Vol. 1, where the extended discussions between Joe and Seligman forestalled any allegations of misogyny or exploitation, the second half instills a permanent wince on the viewer’s face and leaves us regretting how we spent the last four hours.

Von Trier has no interest in a Freudian interpretation of Joe’s sexual psychology, thank goodness, otherwise her relationship with her father (Christian Slater) may have been incestuous, but he also never reconciles the tricky nature of a male director defending a female nymphomaniac—although, clearly he identifies with the androgynously named protagonist. The director’s association with the Freud quote at the beginning of this review ends with his persistent investigation of women characters throughout his career. He represents Joe as a lonely, tragic figure isolated by her desire, and through Gainsbourg’s daring portrayal as Joe, Nymphomaniac is novelistic and fascinating at times, at others downright absurd and grotesque. From von Trier’s need to depict such extreme sex acts in Joe’s story, his film prompts what are often reluctant but undeniably necessary discussions about understanding the nature of sexuality. For a moment, von Trier even manages to find deeply profound meaning in the recurring line, “Fill all my holes, please.” But what might’ve been an incredibly moving and emotionally profound psychosexual epic is cheapened on a devastating scale by the director’s juvenile humor, tiresome desire to shock, and finally, by his need to end Nymphomaniac with an underwhelming and ugly touch of irony.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

As the season turns toward gratitude, I’m reminded how fortunate I am to have readers who return week after week to engage with Deep Focus Review’s independent film criticism. When in-depth writing about cinema grows rarer each year, your time and attention mean more than ever.

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your moviegoing—whether it’s context, insight, or simply a deeper appreciation of the art form—I invite you to consider supporting it. Your contributions help sustain the reviews and essays you read here, and they keep this space independent.

There are many ways to help: a one-time donation, joining DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or showing your support in other ways. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review