Nosferatu

By Brian Eggert |

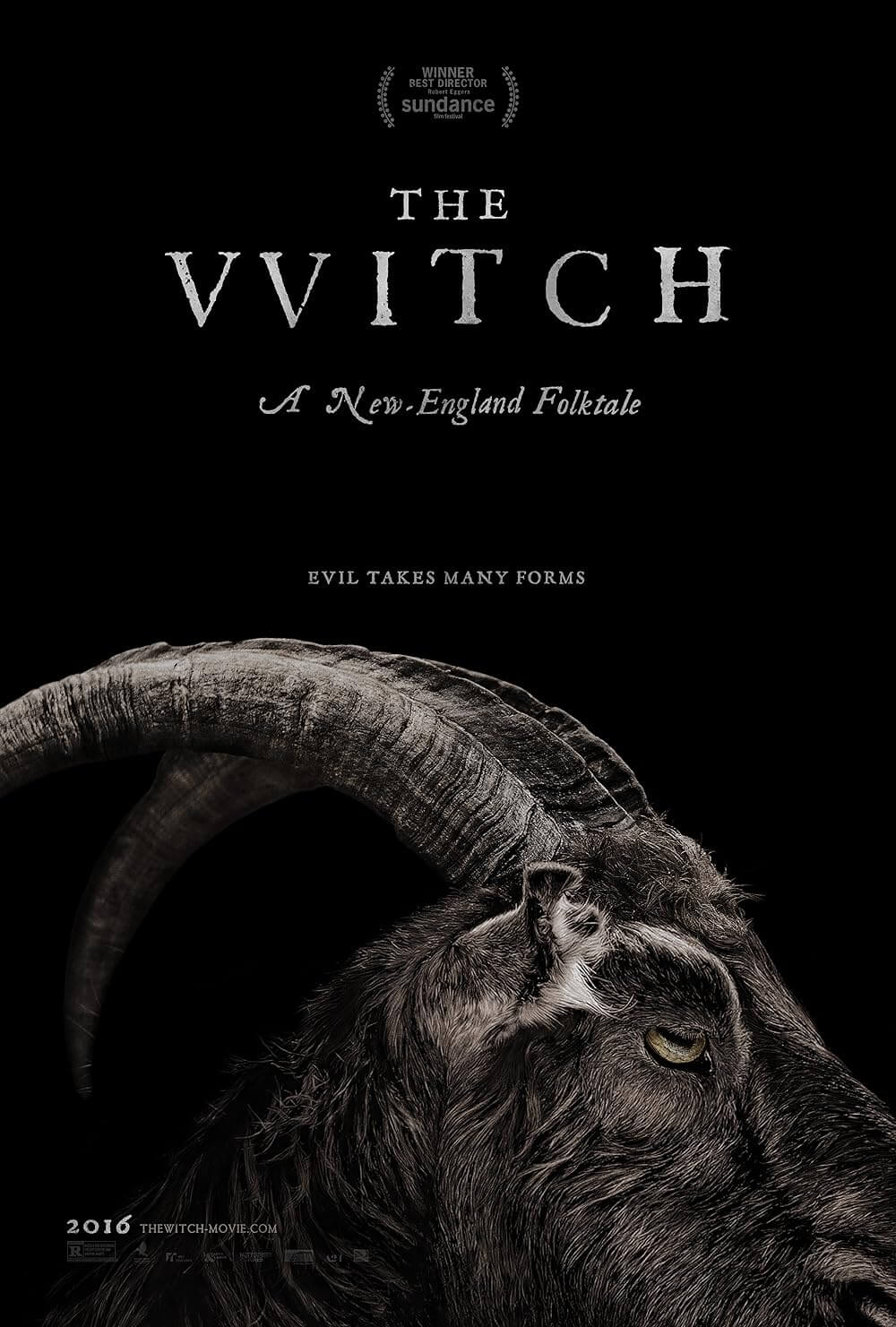

Once again immersing himself in the history and folklore of old, Robert Eggers applies his fastidious knack for detail to Nosferatu, another of the filmmaker’s beautiful, haunting visions. He doesn’t rethink the tale from a contemporary perspective, as another filmmaker might. Instead, he transports the viewer into the past, inhabiting a specific place and time that can feel backward, superstitious, and rooted in mysticism. This has been his approach since his memorable debut, The Witch (2016), which established his interest in research, period-appropriate language, and avoiding anachronisms—aside from the presence of a camera, of course. Eggers continued in this vein with The Lighthouse (2019), his best film, which I initially undervalued, about two lighthouse keepers beset by isolation and seafaring lore. And while The Northman (2022), steeped in Viking violence and imagery, was considered a commercial failure, that didn’t stop Focus Features from also distributing his latest, another perfectly calibrated tale rooted in arcane fears and historicity, albeit shaped by Eastern European legends and themes of sexual repression.

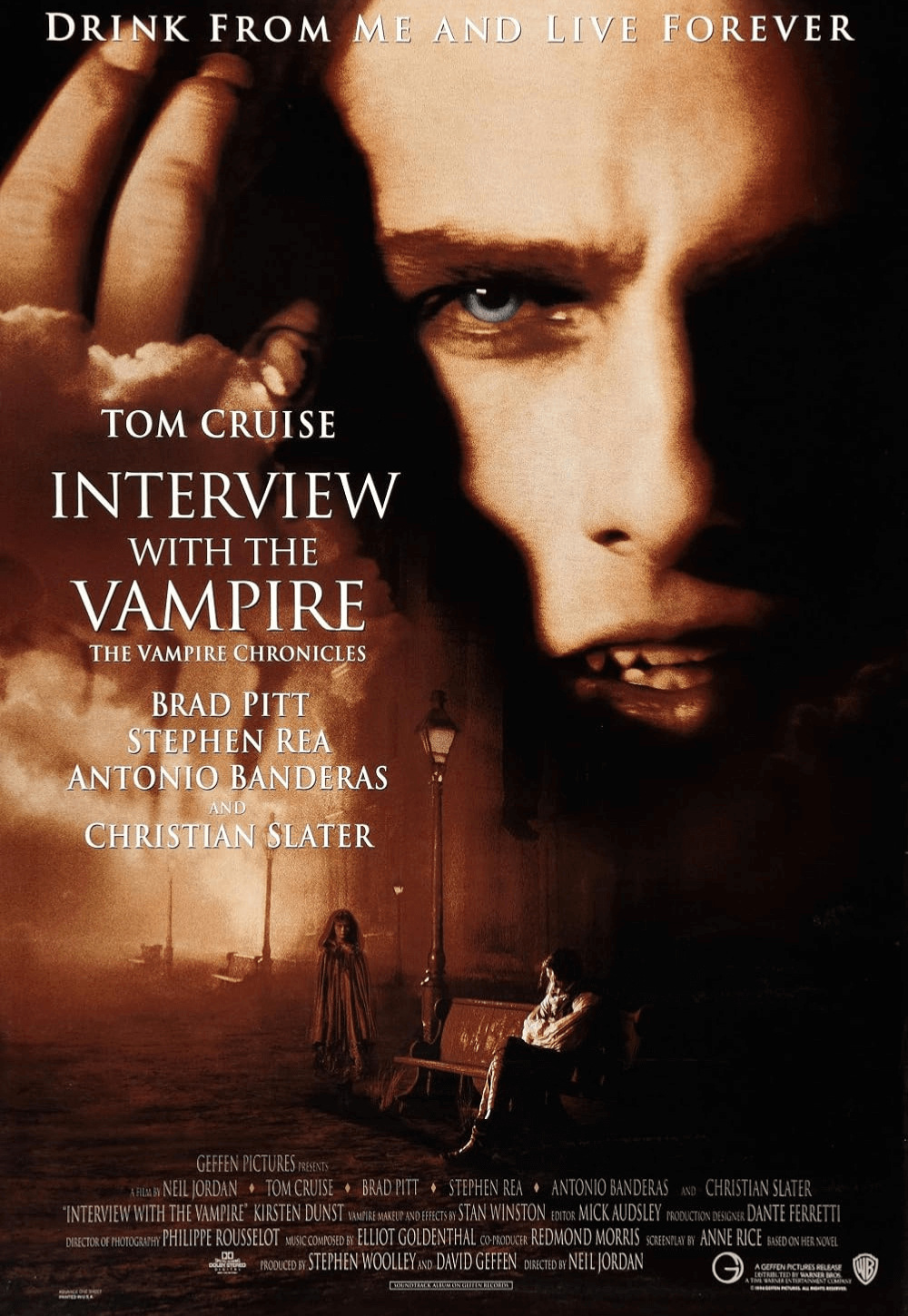

Nosferatu is also unique in Eggers’ career for rethinking an existing book and movie, whereas his earlier films used various historical writings as inspiration. Nosferatu is a remake that credits F. W. Murnau’s 1922 silent classic, Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror, a thinly veiled rip-off of the other credited source, Bram Stoker’s 1897 book, Dracula. Countless iterations of Stoker’s book have appeared in movies, from its iconic direct adaptation in 1931, directed by Tod Browning, to Hammer’s series of Dracula movies starring Christopher Lee. The most apparent aesthetic influence on Eggers is Francis Ford Coppola’s 1992 film, Bram Stoker’s Dracula, a sensational and dazzling production, though it goes uncredited. Eggers uses comparable formal trickery and visual flourishes as Coppola. The same might be said of Werner Herzog’s Nosferatu the Vampyre (1979), starring the volatile Klaus Kinski. If you’ve seen these earlier versions of Nosferatu or Dracula, Eggers’ latest won’t have many surprises, which robs the material of the novelty so central to his previous films.

Eggers wraps his well-trodden scenario in the ancient notion that women with sexual appetites are harbingers of horror and doom. In stories, seductive women often welcome or take the shape of abhorrent evil: tales of Pandora, Medusa, the Whore of Babylon, Lilith, and the Greek Sirens all frame sexual women as dangerous. Obviously, this is not a modern perspective, nor does Eggers endorse such views, but he deploys them in Nosferatu as part of his immersion into the period. In the first scenes in nineteenth-century Germany, Ellen (Lily-Rose Depp), alone and yearning for company, sends out some manner of psychic signal, pleading to be satiated. She awakens the long-dormant ancient force, Count Orlok (Bill Skarsgård), who unlocks her sexuality and haunts her for years. Jump forward to 1838, with Ellen newly married to Thomas Hutter (Nicholas Hoult), a real estate agent struggling for financial independence. Compelled by his employer, Herr Knock (Simon McBurney), Thomas agrees to a “great adventure” in Transylvania, where he will finalize the paperwork for Orlok to acquire a property in Germany.

The story is incessantly familiar to those acquainted with the earlier Dracula or Nosferatu stories, with few surprises along the way, from the creature’s deathly voyage across the sea to the plague of rats Orlok brings with him. But Eggers excels at applying his particular vision. For instance, when Thomas arrives at Castle Orlok, he faces a disturbing, ghoulish Count whose looming presence is genuinely unnerving. Skarsgård rolls his Rs and speaks in a guttural voice, affecting the same Kubrick stare he used as Pennywise the Clown in the 2017 and 2019 adaptations of Stephen King’s It. Eggers forgoes the notion that his villain might appear as a seductive, younger man, as shown in Murnau and Coppola’s versions. Rather, Orlok looks like a living corpse with green-gray colored skin. Though, he still sports the mustache and comb-over he had in life, a standard for Eastern European nobility of his time. When he drinks from Thomas and later Ellen, Orlok does not pierce his canines into their necks for a kiss-like penetration. He bites down on their chest, drinking in vast swallows, requiring bodily movements that suggest he’s consuming liters with each gulp.

Nosferatu is filled with terrific physical performances. Hoult coveys Thomas’ terror over Orlok with a sweaty, strained appearance. Depp is also excellent as Ellen, who’s receptive to supernatural signals and often descends into seizures, both sexually coded and epileptic. Her sad, upturned eyes show melancholy and corruption. It’s a performance worthy of an expressive silent film actor. Giving another unforgettable turn in an Eggers film after The Lighthouse and The Northman, Willem Dafoe plays the resident Van Helsing, here named Prof. Albin Eberhart von Franz, a wily eccentric with an affinity for cats and the occult. If Nosferatu is mostly self-serious and devoid of humor, Dafoe introduces a few choice lines that spark laughter. With a hilarious delivery, he tells Thomas’ friend, Friedrich Harding (Aaron Taylor-Johnson), whose wife (Emma Corrin) and children fall victim to Orlok, “I have seen things in this world that would make Isaac Newton crawl back into the womb.” Even zanier is the madman Knock, the Renfield by another name, whom McBurney plays with uninhibited zeal.

Eggers’ screenplay boasts rich dialogue and themes that feel rooted in the era, and, smartly, he avoids intellectualizing or psychoanalyzing the vampire myth. After all, the story takes place a few decades before Sigmund Freud became active. Still, many of the fears in the film stem from the fear of male sexual inadequacy and female desire, and the tendency to transfer those terrors onto a monstrous figure. Given the persistent, cadaver-like appearance of Orlok, Eggers also maintains a chilling undercurrent: Labeled a “demon” more often than a vampire, Orlok’s presence is less about seduction and sexy vampire behavior and more about being a specter over the characters. That’s what makes Eggers’ version so effective. Even so, the sheer exposure of this story prevented me from connecting with the moment-to-moment emotional experience. In both of my viewings, I was less invested in the narrative than appreciative of the artistry, technique, and conceptual agenda driving the film.

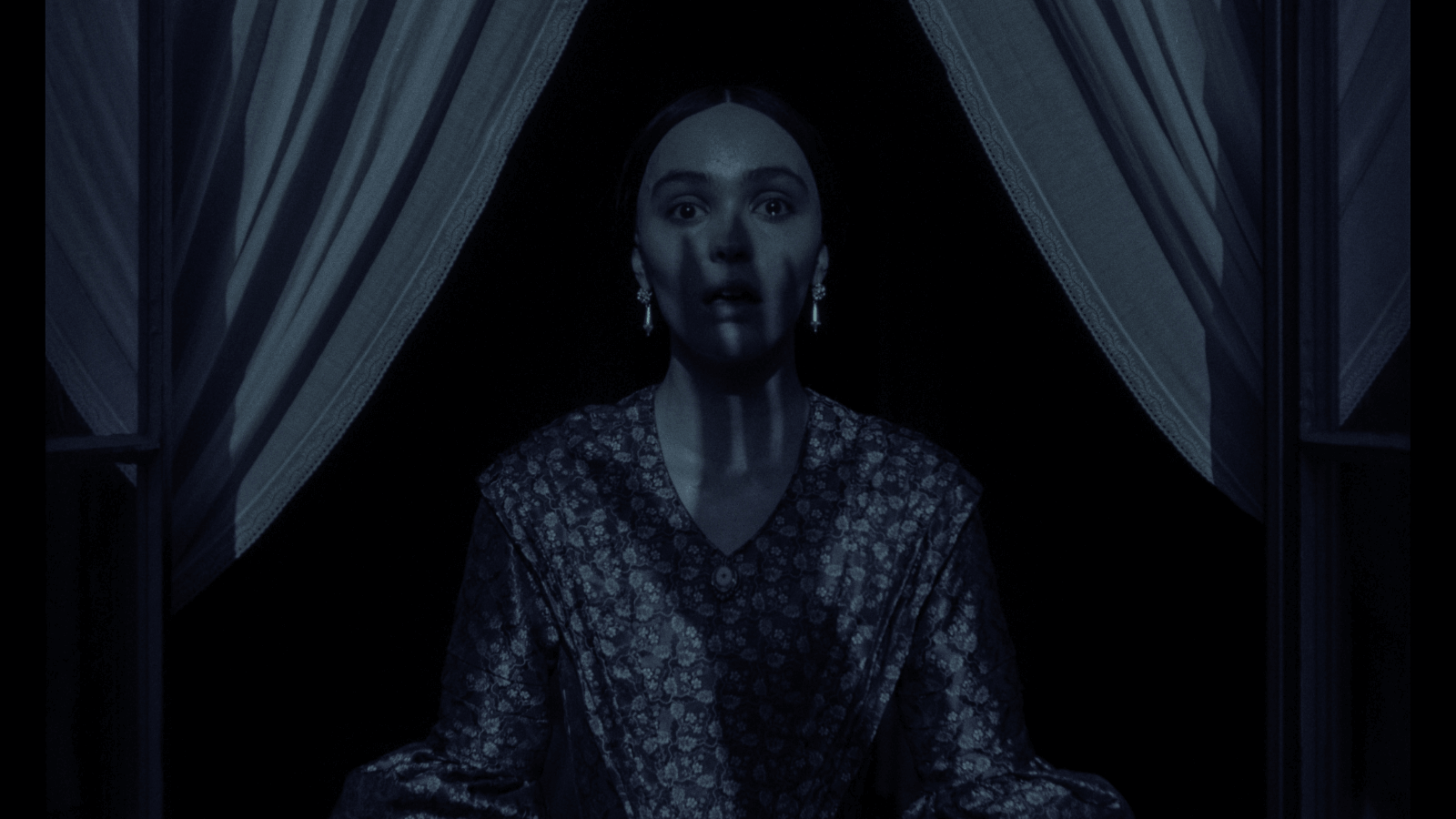

Every shot conceived by Eggers and cinematographer Jarin Blaschke is a wonder, from the driverless carriage framed by a forest path and accented by delicate snowfall to the persistent use of symmetrical imagery to give the film a classical, painterly quality. Eggers again teams with production designer Craig Lathrop and costume designer Linda Muir, creating an impeccable-looking presentation. At times, Nosferatu appears lit by natural light sources, such as candles or overcast skies, resulting in sfumato compositions. Elsewhere, the film seems to glow by artificial moonlight, with a dreamlike blue-gray shimmer during nighttime scenes. Only some of the CGI used to render Orlok’s looming presence raises visual doubts. The exception is the film’s grotesque final shot that recalls paintings of Death, represented as a rotting corpse, usually accompanied by a young woman to denote that youth and beauty are fleeting—an image that stayed with me long after the end credits.

Watching Nosferatu, I wished I hadn’t seen so many other versions of this story. I wished that I could put those experiences in a box and store them somewhere else, allowing myself to be confronted by this tale for the first time. Perhaps the film would have lasted longer in my mind; instead, it proved to have little staying power. But it’s a minor failing of Eggers that his dour and dark picture never transcends those earlier versions, particularly the Coppola film’s dialed-up-to-eleven energy and more emotionally anchored pitch. Regardless, there’s much to admire about Eggers’ take. It’s a sublimely gorgeous production populated by skilled actors and executed with staggering attention to detail. That Nosferatu does not surmount my overexposure should not diminish the director’s technical achievement, which is a wonderfully realized and calibrated piece of filmmaking. I will remain envious of viewers whose first Nosferatu or Dracula experience is with this film.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review