Nope

By Brian Eggert |

An unmoving cloud. Metal objects falling from the sky. Tinny screams from above. A house drenched in blood. Among these many unsettling details in Jordan Peele’s Nope, his third film and most accomplished thus far, is the sight of two animal eyes staring right at the viewer. Shot by cinematographer Hoyte van Hoytema using IMAX cameras, the film makes excellent use of the large-format screen, prompting the audience to search the skies in many vast compositions for signs of something. And yet, one of the most unnerving images occurs indoors when a chimpanzee’s face fills the enormous frame. By this point, Peele has already implanted dread about the animal named Gordy, the star of a 1990s sitcom. Gordy brutally attacks his co-stars in a disturbing scene that reverberates throughout the film. However, the sight of the chimp, both in the first shot and later when a character remembers the attack, hints at the more extensive commentary Peele makes about our culture’s addiction to looking and recording. Whether it’s a bystander with a smartphone or a reporter hunting grisly footage for the evening news, people feel compelled to look, even when it’s against our best interest. Peele weaves that thematic undercurrent throughout his film, using unforgettable imagery and formal bravado to reinforce his ideas to spectacular effect.

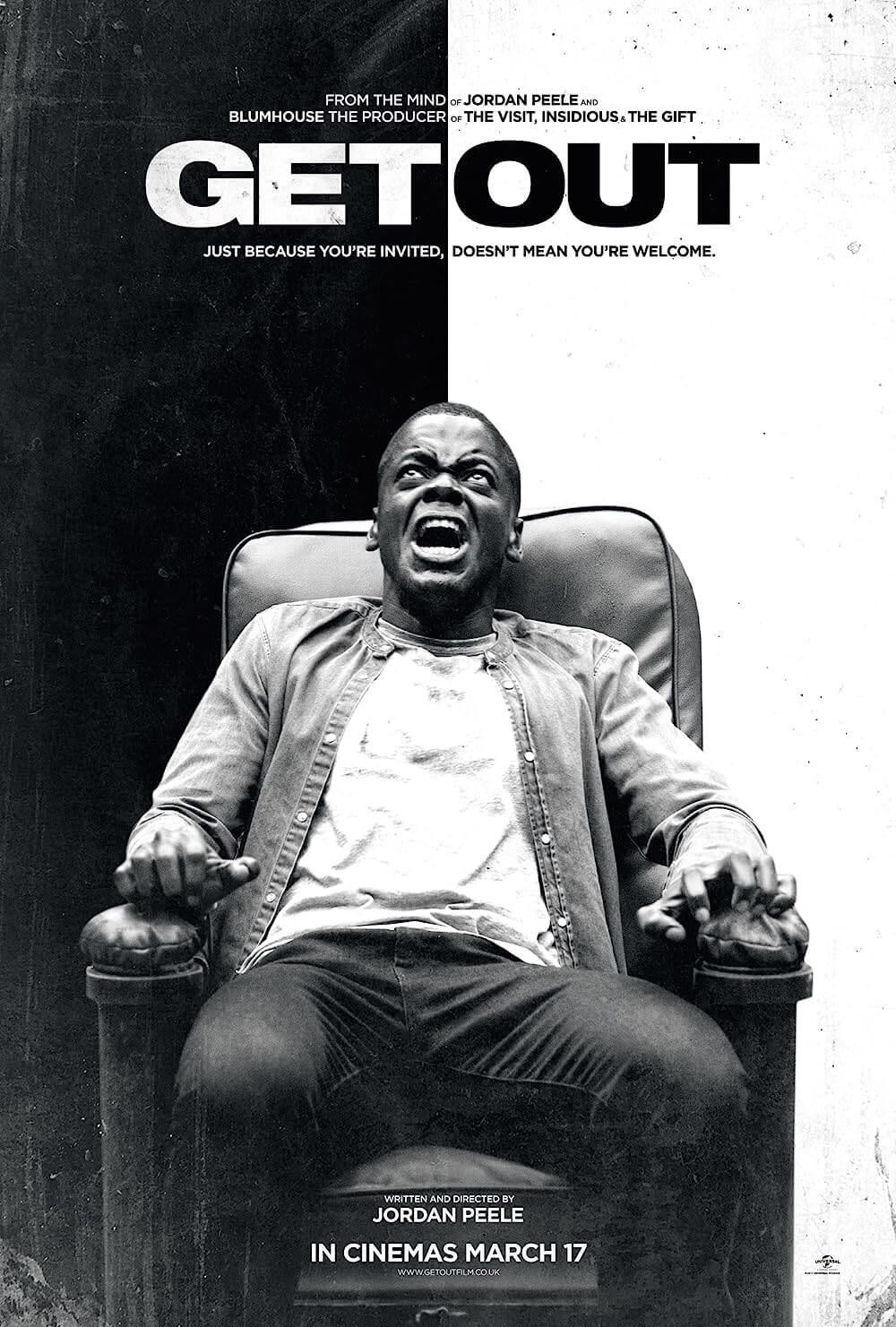

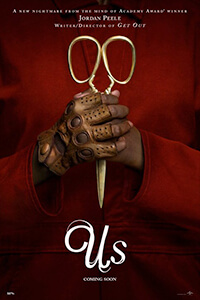

The result is not only Peele’s most thoughtfully considered work in its unity of form and function, but it’s a rousing blockbuster about scopophilia—a pure cinematic theme deployed by masters from Alfred Hitchcock to Michael Powell to Steven Spielberg. That last name on that list stands out in particular since Nope shares elements of Jaws (1975) and Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977). The list of Peele’s subtle references could go on and on, though his film never feels like a pastiche. Rather, he creates a marvelously inspired genre variation comparable to his claustrophobic debut, Get Out (2017), and his more ambitious but less satisfying follow-up, Us (2019). Once more, Peele casts Daniel Kaluuya and, again, uses the actor’s wide eyes to engrossing effect. Kaluuya plays O.J. Haywood, an introverted horse rancher whose family operates a Hollywood animal-wrangling business. At their isolated farm in Southern California early in the film, O.J. looks up and sees something he doesn’t understand. The shot recalls so many in Spielberg’s body of work that concentrates on the awed spectator rather than what caused such astonishment—think the terrified images of Chief Brody in Jaws when he sees the shark or when Alan and Ellie first see a dinosaur in Jurassic Park (1993). The shot is raw empathy.

Peele’s evident interest in film history weaves its way into the story, which unfolds mainly around the Haywood ranch. O.J. and his buoyant younger sister Em (Keke Palmer, superb) hail from a family with a connection to Eadweard Muybridge’s foundational short, “The Horse in Motion” (1878), featuring a Black jockey riding a horse—their ancestor. “Since the moment pictures could move,” Em tells a production crew, “we had skin in the game.” And then there’s Ricky “Jupe” Park (Steven Yeun), a former child actor from the sitcom that co-starred Gordy the chimp, based on a disturbing real-life account of the animal actor named Travis. The experience with Gordy (played in motion capture by Terry Notary, from 2017’s The Square) haunts Ricky, but not so much that he’s unwilling to exploit his trauma or relive the experience at a safe distance by laughing about its SNL spoof. Ricky has since grown up and launched a modest Western theme park, Jupiter’s Claim, not far from the Haywoods’ ranch. Ever since O.J. and Em’s father (Keith David) died in a freak accident—supposedly from metallic debris dropped from an airplane—they have struggled to maintain their family business. As a result, Ricky and O.J. have started discussions about the theme park absorbing the ranch.

Peele’s sharp screenplay establishes these characters before introducing the hook—an enormous disc floating silently behind the clouds in the same valley as the ranch. O.J. notices it first, moving “too fast, too quiet” to be anything known—its arrival signaled by power outages. But the UFO also presents an opportunity. If they can acquire concrete proof of extraterrestrials using top-notch camera equipment—from Frye’s, installed by an affable and intrigued employee, Angel (Brandon Perea)—they can land the money shot of UFO footage, earn a hefty payday, and not have to sell the ranch to Ricky. Angel, who comically inserts himself into the situation, acknowledges that the US Navy already released “shitty footage of exact proof” of UFOs (now called UAPs), but detailed footage awaits. What ensues is a tension-riddled game of cat-and-mouse between the now three spectators armed with cameras and the mysterious object that flies overhead and occasionally sucks a horse into a large opening at its center.

Peele’s sharp screenplay establishes these characters before introducing the hook—an enormous disc floating silently behind the clouds in the same valley as the ranch. O.J. notices it first, moving “too fast, too quiet” to be anything known—its arrival signaled by power outages. But the UFO also presents an opportunity. If they can acquire concrete proof of extraterrestrials using top-notch camera equipment—from Frye’s, installed by an affable and intrigued employee, Angel (Brandon Perea)—they can land the money shot of UFO footage, earn a hefty payday, and not have to sell the ranch to Ricky. Angel, who comically inserts himself into the situation, acknowledges that the US Navy already released “shitty footage of exact proof” of UFOs (now called UAPs), but detailed footage awaits. What ensues is a tension-riddled game of cat-and-mouse between the now three spectators armed with cameras and the mysterious object that flies overhead and occasionally sucks a horse into a large opening at its center.

Peele negotiates the line between fun and terror as Nope contains several breathless sequences, demonstrating his absolute control of the craft and his knack for manipulating an audience. When O.J. finds himself confronted by curious shadows inside a barn at night, there’s playful tension at work in the dreadful quiet. But the director is careful not to reveal too much too soon, having learned what Spielberg taught us in his films mentioned above about letting the audience’s imagination do the work. Or, if you prefer, what Hitchcock taught us about suspense—that implanting a knowledge that something’s going to happen, it’s just a matter of when, leads to incredible thrills. In that sense, Michael Abels’ nerve-fraying score and van Hoytema’s careful lensing build tension to unbearable levels without the film ever giving away its secret before the intended reveal. Peele’s scopic frame for exterior shots, too, becomes an essential device for building the uncertainty and dread the characters feel, especially as more about its nature is revealed. This is not a film to watch on iPhones or even a small TV. The images are meant to consume you.

On that note, and in the interest of preserving Nope’s secrets, skip to the last paragraph if you want to remain unspoiled. Part of the film’s effectiveness is that it’s not just another UFO movie, despite its apparent nods to War of the Worlds (especially Spielberg’s 2005 version). Peel cleverly links the film’s themes about the dangers of spectacle with a novel conceit: instead of a flying saucer containing Martians, the disc itself is an animal that, not unlike Gordy, has been provoked. It feeds from a territory of a few lightly inhabited acres. Ricky has been feeding the thing, barking to his theme park’s scattered rubbernecks, “What if I told you that in about an hour, you’ll leave here different?” But like Gordy, the alien animal has been provoked too many times, and eye contact with a predator is never advised. Animal experts say you should never look a bear or gorilla in the eyes. Yet, the Haywoods’ desire to capture video of the flying creature has led to a veritable rampage of Gordy-level proportions. Still, as with Gordy, people cannot look away even in the saucer’s bloody aftermath. “It’s a spectacle—people are just obsessed,” says Ricky about his Gordy memorabilia, locked away in a secret room that fanatics pay top dollar to access.

Indeed, once the Haywoods learn more about the creature, O.J. doubles his resolve, even if he’s terrified—cue hardy laughs from Kaluuya’s flat delivery of “nope.” Herein lies the subtle character work from Kaluuya and Palmer in their internal and external roles, respectively. Peele’s tightly wound scripting gives each character reasons for their behavior in the wake of their father’s death, complete with backstories and feelings about their sense of ownership over the ranch and thus their willingness to risk their lives for it. When faced with a flying animal that inhales its meals and spits out anything it cannot digest through the same hole, like a starfish, they each react the way they have been taught. O.J., ever the animal trainer that his father was, realizes he must play by the animal’s rules and respect its ornate posturing—leading to a dazzling sequence in the final act that recalls the crop duster scene in North by Northwest (1959) combined with the monstrous threat at the end of Tremors (1990). Em’s journey goes from wanting “the Oprah shot” to shutting down in survival mode, making her eventual turn in the rousing finale (complete with a visual nod to 1988’s Akira) feel triumphant on a personal level as well.

Indeed, once the Haywoods learn more about the creature, O.J. doubles his resolve, even if he’s terrified—cue hardy laughs from Kaluuya’s flat delivery of “nope.” Herein lies the subtle character work from Kaluuya and Palmer in their internal and external roles, respectively. Peele’s tightly wound scripting gives each character reasons for their behavior in the wake of their father’s death, complete with backstories and feelings about their sense of ownership over the ranch and thus their willingness to risk their lives for it. When faced with a flying animal that inhales its meals and spits out anything it cannot digest through the same hole, like a starfish, they each react the way they have been taught. O.J., ever the animal trainer that his father was, realizes he must play by the animal’s rules and respect its ornate posturing—leading to a dazzling sequence in the final act that recalls the crop duster scene in North by Northwest (1959) combined with the monstrous threat at the end of Tremors (1990). Em’s journey goes from wanting “the Oprah shot” to shutting down in survival mode, making her eventual turn in the rousing finale (complete with a visual nod to 1988’s Akira) feel triumphant on a personal level as well.

Peele’s interest in our fixation on seeing something uncanny extends beyond respect for Nature into a critique of what filmmakers will do to capture a spectacle. A few subplots in Nope serve as Peele’s treatise on filmmaking ethics, such as when the Haywoods request help from a maverick cinematographer, played with deadpan brilliance by Michael Wincott. The character’s presence and desire to push a little further than planned calls to mind filmmakers who will do anything to get the impossible shot, even if it means putting their cast and crew at risk. This, in turn, raises questions about film history’s accounts of people going too far to get the shot: Michael Curtiz used tripwires to topple horses, killing over 25 of them to capture a sequence in The Charge of the Light Brigade (1936); William Friedkin put Linda Blair through hell to get the performance he wanted in The Exorcist (1973); Werner Herzog went mad trying to tame a Peruvian jungle to shoot Fitzcarraldo (1982). Peele raises an eyebrow at these hypermasculine antics, given how safety remains a top priority in today’s more responsible filmmaking environment.

For all its fantastic showmanship and conceptual vision, Nope is also an accomplished third film that finds Peele’s ideas working in unison with his formal techniques to brilliant effect. Moreover, after just two films, Peele has established distinct visual and tonal touches, a knowing sense of humor, and a relationship with his audience as evident as any established auteur. That he’s been consistent from the relatively micro Get Out to his midlevel Us and now to this large-scale production is something practiced by only the most confident filmmakers. And while his previous two features are culturally more significant and thematically more weighty, Nope shows that Peele has worked out some of the kinks in his earlier work and found intentional, symbolic uses for the camera. It may be a big summer blockbuster about a UFO, but it’s an expertly crafted one with something on its mind, which is more than can be said for most other mega-budget extravaganzas. Whenever a film of this size, scale, and ambition asks viewers to think about why and how they’re looking at the screen, that’s something rare and special.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review