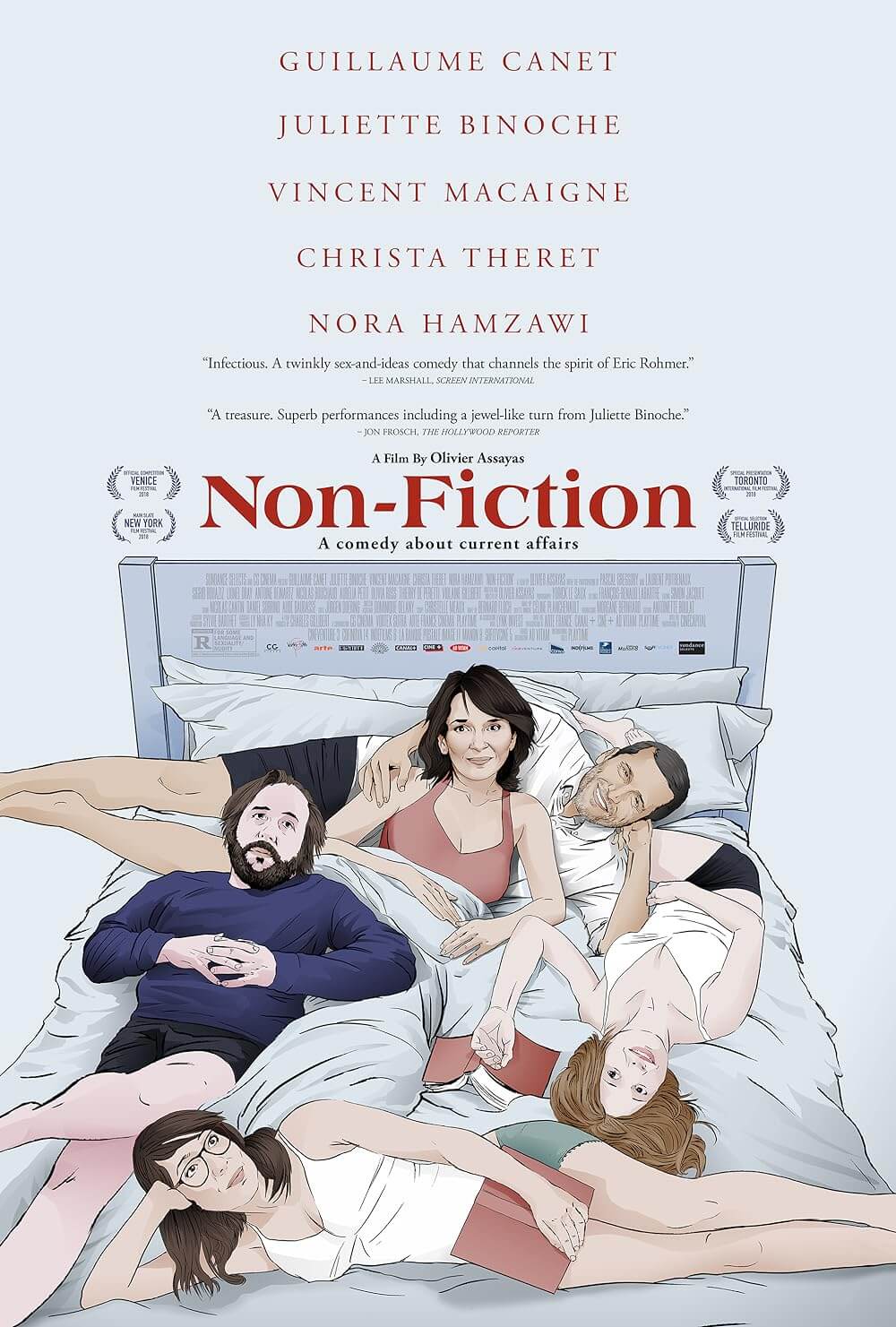

Non-Fiction

By Brian Eggert |

Juliette Binoche and Olivier Assayas have been interconnected since 1985, when the former film critic collaborated on a screenplay with André Téchiné and released Rendez-vous, a sordid melodrama featuring Binoche as the sexually ambitious Nina. After arriving in Paris, Nina beds a string of men only to find herself fixated on one of them, who quickly goes missing. Nina’s search for him leads to her presence on the French stage, playing none other than Juliet Capulet. Nina, a sexualized symbol of what drives actors, made Binoche an international star, and she’s since embodied several other actor characters who are compelled to perform either by passion or necessity. Over the years, Binoche has appeared in Assayas-directed films several times, including Summer Hours (2008), a family drama about the meaning we assign to artifacts and the role they play in our memories. Next came Clouds of Sils Maria (2014), which spawned from Binoche’s challenge to her director to make a film that tapped into the identity of filmworkers. Assayas responded by writing one of Binoche’s best roles as Maria, a diva of the stage and screen who is averse to technology and resentful of how the digital age, from social media self-promotion to 3-D superhero movies, somehow diminished her yet left her envious.

In many ways, Assayas and Binoche’s latest joint effort, Non-Fiction, feels like an extension of the themes explored between director and actress in their earlier collaborations, though resituated in the publishing world. Once again, Binoche plays an actress, named Selena, who stars on a dull television series called “Collusion” as a “crisis management expert,” also known as a cop. Selena might be another version of Maria who has embraced developments in the entertainment industry, for better or worse. Television used to be a step down from feature-length films, but now those two platforms have blended and become almost indistinguishable given the prevalence of streaming and binge-watching. “Addiction is our default setting,” observes one character about the trends of media consumption. Maria would be unable to exist in such intractable carryover, whereas Selena begrudgingly makes a living from the trend. But Selena is a supporting character in Non-Fiction, whereas its themes dwell on the state of literature, the Digital Age, and whether we’re in a state of cultural digression or progression. At the forefront are questions about the advantages and disadvantages of physical books and e-readers, public libraries and Google Books (“the largest library in the world”), or Amazon’s algorithms that predict your tastes and relevance of critical evaluation.

Assayas’ dry and observant comedy unfolds in the form of dynamic conversations and debates that take place in Parisian cafés, at dinner parties, or in post-coital discussions. His characters try to grasp the state of things by defining the fragmentary state of our “post-truth” reality, where everyone has their own sense of truth because online platforms and segmentation allow for cultural bubbles to exist independently of one another. Much of the film centers on Selena’s husband, Alain (Guillaume Canet), who runs a venerable publishing house in Paris that has explored the idea of moving from print to digital, although he’s something of a purist and resists committing to the change. His company hires Laure (Christa Théret), a digital transition specialist who has committed herself to legitimizing the digitally written word, thus enabling the democratization of writing and information access. But in the mad rush to make sure everyone has a voice, Alain wonders what is lost, even as he acknowledges there’s no backtracking. At the same time, he admits that writing and publishing books are inherently out of sync with the ever-changing times.

Assayas’ dry and observant comedy unfolds in the form of dynamic conversations and debates that take place in Parisian cafés, at dinner parties, or in post-coital discussions. His characters try to grasp the state of things by defining the fragmentary state of our “post-truth” reality, where everyone has their own sense of truth because online platforms and segmentation allow for cultural bubbles to exist independently of one another. Much of the film centers on Selena’s husband, Alain (Guillaume Canet), who runs a venerable publishing house in Paris that has explored the idea of moving from print to digital, although he’s something of a purist and resists committing to the change. His company hires Laure (Christa Théret), a digital transition specialist who has committed herself to legitimizing the digitally written word, thus enabling the democratization of writing and information access. But in the mad rush to make sure everyone has a voice, Alain wonders what is lost, even as he acknowledges there’s no backtracking. At the same time, he admits that writing and publishing books are inherently out of sync with the ever-changing times.

Something about this talky French comedy makes these conversations feel part of a larger, often hilarious human drama instead of a series of forced remarks about the state of culture by way of publishing. One of the authors at Alain’s company is Léonard (Vincent Macaigne), a drab type who writes “feel-bad” books in an “auto-fiction” style, drawing from incidents in his life and thinly disguising them on the page. His latest manuscript, titled “Full Stop,” is an account of his sordid affair with Selena, complete with a salacious scene detailing a sex act performed in a movie theater during Michael Haneke’s The White Ribbon (2009)—a comic thread that feels inspired by the Seinfeld joke about making-out during Schindler’s List (1992). Alain refuses to publish it, perhaps because he suspects that Selena is the subject of Léonard’s novel; however, Selena doesn’t mind, and she encourages her husband to change his mind. Nora Hamzawi plays Valérie, a political advisor who suspects Léonard, her lover, is unfaithful. But the decidedly French relationships here have a way of interconnecting in the most diplomatic of romantic pentagons.

Assayas chose to shoot Non-Fiction on Super 16 film stock, giving the production a visible, authentic grain—an important choice in a film that deliberates between physical or digital mediums. His cinematographer, Yorick Le Saux, who also shot Clouds of Sils Maria and Personal Shopper (2017), adopts a different visual aesthetic than those works, or his collaborations with Luca Guadagnino (I Am Love, A Bigger Splash). The camera is fluid but recessive, navigating through interior spaces to follow the conversations as they progress, grow heated, or find moments that balance ache and humor. Watch the scene in which Léonard confesses his affair to Valérie; she moves around their living room, switching from sitting in a chair to a couch to standing, as Léonard must adjust his position, desperate to seem open and accommodating in the wake of his infidelity. Assayas has a sly way of using space to achieve both intimacy and humor in such scenes. At other times, his writing cuts into his characters, as when Valérie compliments her husband’s performance on a radio interview by saying, “I was surprised. You didn’t stutter as much as you usually do.” In a way, the exchanges in Non-Fiction recall the cruel games played at the Versailles court in the French period drama Ridicule (1996).

The content of Non-Fiction is a few years old by now, assuming it took Assayas several months to write, and then many more months to develop, shoot, and complete. It’s also been on the festival circuit since mid-2018. Even so, his ideas and observations about the state of technology and its effect on culture today are astute, comical, and even insightful. At one point, a character describes the internet as a “supermarket of information in which everyone does their own shopping.” It’s a frustrating condition that at once grants people access to information on an unprecedented scale, yet also furthers our distance from one another and seals those cultural bubbles in a fixed, demarcated ideology. As ever, Assayas is also a most literate cinephile, and he quotes iconic lines of cinema to punctuate the film’s discourse. At a crucial point, Alain uses Igmar Bergman’s Winter Light (1963), about a priest who has lost his faith yet maintains his church out of routine, to draw a comparison to his station at the publishing house. Later, Alain references Luchino Visconti’s The Leopard (1963), remarking, “If we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change.” It’s a fateful, almost apocalyptic quote in this context, using Visconti’s tragedy about the fall of the Sicilian aristocracy as a parallel for the printed word.

The content of Non-Fiction is a few years old by now, assuming it took Assayas several months to write, and then many more months to develop, shoot, and complete. It’s also been on the festival circuit since mid-2018. Even so, his ideas and observations about the state of technology and its effect on culture today are astute, comical, and even insightful. At one point, a character describes the internet as a “supermarket of information in which everyone does their own shopping.” It’s a frustrating condition that at once grants people access to information on an unprecedented scale, yet also furthers our distance from one another and seals those cultural bubbles in a fixed, demarcated ideology. As ever, Assayas is also a most literate cinephile, and he quotes iconic lines of cinema to punctuate the film’s discourse. At a crucial point, Alain uses Igmar Bergman’s Winter Light (1963), about a priest who has lost his faith yet maintains his church out of routine, to draw a comparison to his station at the publishing house. Later, Alain references Luchino Visconti’s The Leopard (1963), remarking, “If we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change.” It’s a fateful, almost apocalyptic quote in this context, using Visconti’s tragedy about the fall of the Sicilian aristocracy as a parallel for the printed word.

Assayas has filled his screenplay with acerbic remarks and assessments of the modern world, from his condemnation of the “unwitty witticisms” written on Twitter to the “incontinent flow” of internet writing. But the joys of Non-Fiction result from the lived-in performances, Binoche and Macaigne above all, and the humor that is subtle at times, more pointed at others. A cute, self-referential gag about Binoche seems to be getting a lot of attention from audiences, but there are heartier and more meaningful laughs elsewhere in the film. However, Assayas avoids easy humor, for the most part, and places his film into the realm of a more serious Woody Allen comedy that’s actually about something. Though he acknowledges that the digitization of art is here to stay, he asks his audience to consider, “Is this good?” Many viewers born in the Digital Age know nothing else, and their answer is perhaps certain. Those who have watched the increased discontinuity of reality, culture, and truth may have a different view. Non-Fiction’s ability to provoke thought and debate among its viewers, while also having a curious optimism about the tactile reality of human relationships, makes it a careful balance of the intellectual and emotional.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review