Noah

By Brian Eggert |

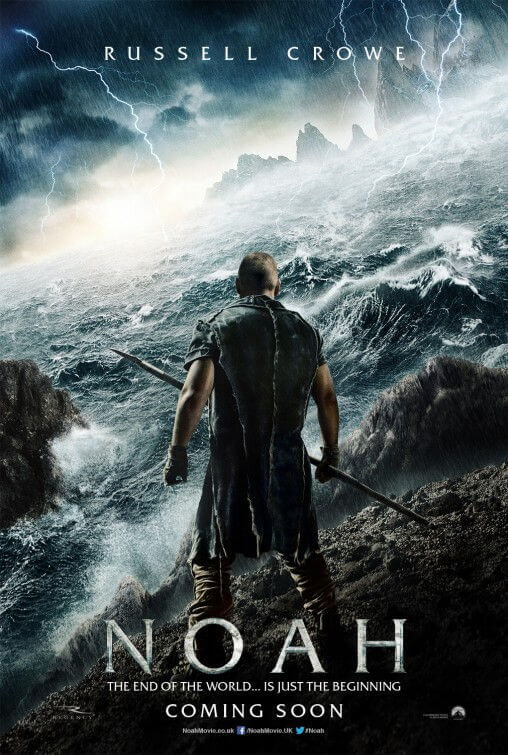

In Noah, director Darren Aronofsky mines the flood myth of Genesis—though its origins derive from older mythologies in ancient Mesopotamia—and presents a picture of epic scope. Central to the film is an existential dilemma for the titular biblical hero, played with much ferocity and gravitas by Russell Crowe. Aronofsky’s rugged and battle-ready version of Noah approaches madness in his struggle to understand his instructions from God, just as the director’s obsessed protagonists from Pi (1998) and The Fountain (2006) endeavored to comprehend their respective origins. But whenever modern interpretations suggest anyone in the Christian Bible might’ve questioned orders from above, the devoutly religious invariably respond with accusations of sacrilege (case in point: reactions to The Last Temptation of Christ), and Aronofsky’s impressive $130 million production backed by Paramount Pictures hasn’t been immune to such impassioned indictments from various religious groups after early screenings. Amid several points that will undoubtedly offend the pious masses is an unexpected reading of the Old Testament that attempts, albeit clumsily, to link allegorical scripture and evolution science. And along with its fantasy-inflected battles and heavy environmentalist commentary, the film is likely to incite keen discussion more than outright protests; but as a result of Aronofsky’s restrained, commercial-minded treatment, viewers not particularly devoted will be left questioning some of the bigger plot holes that have remained gaping since antiquity.

One of the most widely regarded myths to spread across several major religions, the story of Noah’s Ark comes with an irrefutable iconography, and Aronofsky both embraces and reformats that powerful imagery. There’s certainly an Old Testament air to his production, beginning with cinematographer Matthew Libatique’s lensing of almost dystopian volcanic wastelands in Iceland as an alternative to the Middle East. However, a literal “voice of God” isn’t responsible for the mission of our hero. (Indeed, most apparent in the film’s list of controversial issues is the word “god” or, more specifically, the lack thereof; Noah receives messages from a source he calls “The Creator”.) Rather, Noah, a middle-aged family man stricken with a nasty case of theological introspection and disdain for the human race, receives his interpretable instructions from visions brought about first in a dream, and then during a consultation with his wizard-like grandfather, Methuselah (Anthony Hopkins). And so, Noah enlists his wife Naameh (Jennifer Connelly) and sons Ham (Logan Lerman), Shem (Douglas Booth), and Japheth (Leo Carroll) to help build a structure that will allow the Creator to wipe out the unruly population of the Earth and preserve those whom “deserve” to live. In Noah’s mind, this means animal populations should survive, as they are the only innocents made by the Creator. Meanwhile, Ham grows jealous that his brother Shem has found a wife and therein a future with Noah’s beautiful adopted daughter Ila (Emma Watson), even though her womb is barren, and he pines for a wife of his own.

Enter the gristly villain Tubal-cain (Ray Winstone), a descendant of the Cain who slew Abel, and his band of unmerry men desperate to climb aboard the Ark and save themselves, no matter who has to die in the process. They’re a starving and desperate lot, selling their own children for a bite of raw animal flesh. In the film’s prologue, the young Tubal-cain (Finn Wittrock) kills Noah’s father Lamech (Marton Csokas); now the long-ruling king of humanity, Tubal-cain gathers hordes of undesirables, and together they charge Noah’s Ark in epic combat sequences straight out of a Ridley Scott film, complete with armed throngs rushing into battle. Aronofsky digs into Genesis here to conceive a baddie with a substantial religious history and association to our hero, which brings the fable of creation full circle both dramatically and religiously. This also renders the inevitable clash between Noah and Tubal-cain relatable on human terms but decidedly convenient in storytelling terms, as Noah is the last descendant of Seth, the brother of Cain and Abel. Though the ancestral conflict has been manufactured for purely entertainment purposes, this forced plot strain displays base human savagery amidst Tubal-cain and his army, reminding the viewer why the human race in Noah’s time deserves to be obliterated. These scenes serve as a scary mirror of how our current society behaves, and in that creates an association between the two, complete with Noah foretelling the future of human atrocity through staccato flashes of the silhouettes of soldiers making war from ancient times to the present day military garb.

Close- or literal-minded readers of scripture may take issue with several elements in Aronofsky’s handling of the material, though the production boasts fascinating attention to detail. For example, to build the Ark, production designer Mark Friedberg followed actual specifications and erected the massive wooden ship in New York, whereas another Hollywood production less interested in technical realism would’ve just used CGI. (Since most shots of the Ark on the endless sea are CGI anyway, building an actual scale set seems almost pointless in this case.) In other instances, Aronofsky’s script, co-written with Ari Handel, takes liberties to not only expand the rather succinct tale into a full-length feature but to make it entertaining and visually stimulating. Beyond the creation of Tubal-cain, the script uses the Bible’s briefly referenced Nephilim, or fallen angels, which are represented in the film as large rock people, called The Watchers (voiced by Frank Langella, Mark Margolis, and Nick Nolte)—the stony equivalent to Ents from The Lord of the Rings trilogy. These Watchers assist Noah in his construction project and provide a line of defense when the battle scenes gear up. The Watchers are a very odd and ungainly component within the film’s first half, and clearly in attendance to provide obligatory battle scenes with a dash of the fantastical, especially when they burst and turn into gold-glowing angels jetting toward Heaven.

Of course, Aronofsky cannot reconcile some of the oldest questions and physical conundrums of the Noah’s Ark story, no matter how big his budget. Consider how the animals know to show up at the Ark. Did they receive the same vision as Noah? Who knows, but in short order, they arrive in twos and climb aboard the intimidating structure ready for sleep, sedated by a smoke concocted by Naameh. Which, of course, brings into question the logic of flooding the entire Earth when really it’s humanity that’s gone awry. Why eliminate the planet’s various animal populations all because of a few bad seeds in the human race? Sort of extreme, no? Why didn’t the Creator conjure up one of his famous plagues to wipe out his faulty line of human beings? And why do land animals get eliminated, but not fish? Alas, Noah never questions his Creator’s logic, though he wholeheartedly believes his charge is to save animal life, not human. And when it comes up near the end of the film, neither Noah nor his family ever questions how, within their limited reproduction options, they’ll successfully repopulate the planet without the usual maladies resulting from a limited gene pool.

This is a somewhat facetious line of argument against the myth and film on my part, but in another way, it illustrates how Aronofsky conveniently avoided addressing certain illogical aspects of the Noah’s Ark myth so as not to offend his audience. (The film could have easily corrected this by suggesting that, say, more than Noah’s family or just two animals would repopulate their species.) But in other ways, just the opposite is true. In a later scene, Noah recounts the creation of the universe with his family, and we see before us his belief in evolution, energy becoming matter, matter becoming life, ocean lifeforms emerging onto land and advancing from simple to complicated fauna. If Aronofsky was willing to inject evolution into a biblical tale, why not just go all the way and make sense out of the silliest aspect of the Noah’s Ark story—the notion that humanity sprung from such a limited gene source? Indeed, with as many risks as Aronofsky takes, his concessions are far more significant. When the flood’s impressive spectacle has subsided, and we’re left with the characters, Crowe is excellent as Noah, who becomes a drunkard weighed down by questions about why his family was saved and what the Creator’s intentions were. But Noah should be asking how the survivors will repopulate the human race without committing some form of incest.

But I digress. Between the talking rock people and the inconsistent treatment of evolution and reproduction, Noah is remarkably weird and rather perplexing. Aronofsky fails to reconcile his relatively controversial strokes of realism and scientific fact as they interact with the more fantastical, downright far-fetched elements of his interpretation. And his visual sense, so strongly defined in his earlier work, has adopted the flavorless appeal of your average blockbuster. None of his usual body-mounted cameras, dynamic camerawork, or innovative uses of montage are in attendance here. This is strange, since the director’s films Requiem for a Dream (2000), The Wrestler (2008), and Black Swan (2011) have demonstrated that Aronofsky is committed to a complete, fully realized vision. And while Crowe and the rest of the cast give performances packed with emotional heft, the film’s lack of balance prevents it from coming together in any remarkable way, though a few admirable moments are littered throughout. Both as a grand Hollywood spectacle and technical achievement, Noah’s merits cannot be disputed, nor can the film’s inherent ability to cause an uproar among those offended by any interpretation of scripture that doesn’t align with their own. In the end, perhaps the greatest compliment that can be paid to Aronofsky is that he’s made a compelling discussion piece, but a frustratingly uneven one.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review