Nightmare Alley

By Brian Eggert |

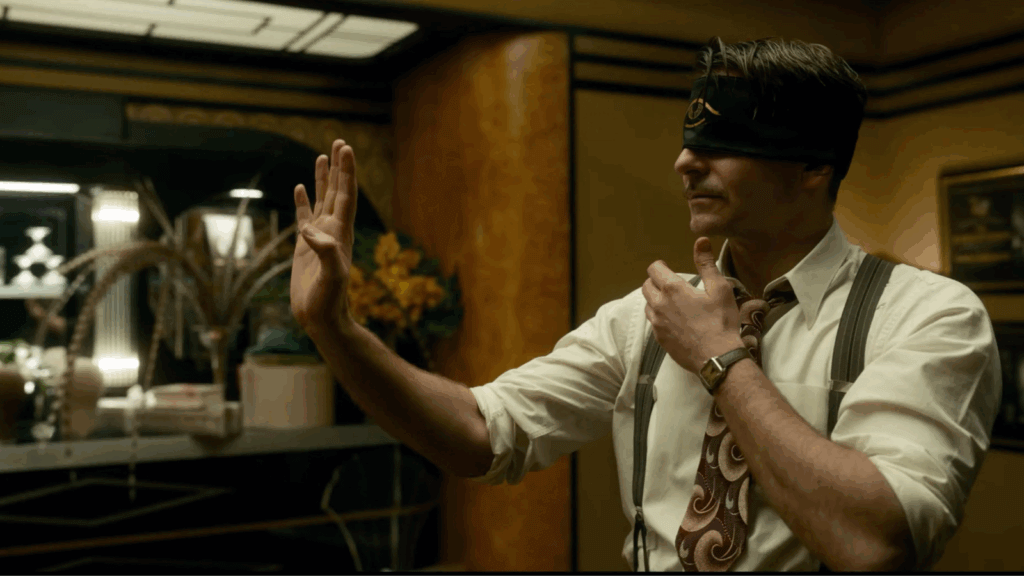

Step right up, ladies and gentlemen, and keep your eyes open for Guillermo del Toro’s Nightmare Alley. That’s right folks, the Mexican fantasist has got a show for you. Watch the screen because here come the performers. Del Toro’s got the human pretzel; Fee Fee the Birdgirl; Major Mosquito, the smallest man you ever saw; the tarantula lady; and Bruno the strong man. And don’t miss the headliner, folks: the one you’ve heard about around town! Stanton Carlisle, the mentalist who can see your past and future. That’s right, it’s Bradley Cooper giving one of his best performances yet. You have to see it to believe it! With the help of his lovely assistant, The Great Stanton will guess the object in your hand, even while he’s blindfolded. How does he do it? Come right here for a closer look, and he’ll peer into your soul with his third eye. When he’s done, you’ll know something about yourself you didn’t know before. So get your hands out of your pockets and get yourself a ticket to the best show in town! And afterward, have we got a special added attraction just for you. Leave the kids at home for this one, parents. It’s a human oddity, the likes of which you’ve never seen. Yes, this monster is a man, but a wild man known as a glomming geek. Just a quarter to see him, and another quarter to watch him eat! Come one, come all! Del Toro’s gotta show you won’t soon forget!

…Barking about Nightmare Alley feels only too appropriate during the overstuffed holiday season. Del Toro’s latest film opens as counter-programming on the same weekend against what might be the year’s biggest blockbuster, Spider-Man: No Way Home. And the surrounding weeks boast mainstream fare and sequels galore, all but ensuring del Toro’s R-rated, 150-minute production—one of his darkest, most serious films yet—goes overlooked. Doubtless, Searchlight Pictures positioned the film for awards consideration after del Toro’s The Shape of Water (2017) earned him Oscars for Best Picture and Best Director. However, not even his stellar cast, which includes Cooper, Rooney Mara, Cate Blanchett, Toni Collete, and Willem Dafoe, will likely be enough to draw holiday moviegoers away from their glut of cinematic fast food. Those who do seek out the film will be treated to an immersive, passionately designed world that eschews the typical fantasies of del Toro’s other work and replaces them with the intrinsic pessimism, cynical mood, and existentialism of classical film noir.

Del Toro and Kim Morgan based their screenplay on the 1946 book by William Lindsay Gresham, a sordid and often shocking text, marked by circus slang, in which the author explores his fixations. When Gresham set out to write his novel, he had just returned from volunteering to defend the Republic in the Spanish Civil War—the setting of del Toro’s The Devil’s Backbone (2003) and Pan’s Labyrinth (2006). Abroad, Gresham heard stories about creating a geek or wild man, the carny attraction where a rock-bottom drunkard bites the heads off live chickens or snakes. The story conveyed the depths of human depravity, not only that an alcoholic could sink so low, but that a person would exploit another in such a vile fashion. Upon returning to the US, Gresham combined the jarring geek story with his fascination for tarot cards and psychoanalysis, as well as his personal battle with alcohol. The result introduced sideshow slang into the literary mainstream, while the downward spiral narrative played like a Greek tragedy about the depths of addiction and the willful manipulation of others.

Moreover, del Toro’s longtime interest in circus culture and human oddities makes him uniquely suited to adapt Gresham’s book. When his exhibit At Home with Monsters, a traveling cabinet of curiosities, toured in 2017, it boasted statues and collectibles from Tod Browning’s Freaks (1932) alongside Frankenstein and Lovecraft memorabilia. Today, del Toro regularly explores monstrosity in the form of vampires, ghosts, and fantastical creatures, but the study and peculiar fascination with physical abnormalities first became all the rage in the nineteenth century, especially after John “The Elephant Man” Merrick and showman P.T. Barnum took them from backroad sideshows to popular culture. Nightmare Alley features a few sideshow attractions, sure, but it’s more interested in la bête humaine, epitomized by Stanton Carlisle—Gresham’s doomed protagonist whose dark past, moral liberties, and tortured conscience represent a different kind of monstrosity. Stan drifts into a meager job at a carnival early in the film. He doesn’t speak for several minutes of screentime, until the carnival’s resident geek escapes into the funhouse. Helping the carny crew get the geek back into his cell, Stan follows the growling shell-of-a-man into a hellish attraction decorated with demons, oppressive and judging eyes, and a mirror that reads, “Take a look at yourself sinner.” When he finally speaks, it’s to the man who heralds precisely what’s to come for Stan.

Haunted by dreams of what he was and will become, Stan, more intelligent and talented than most, quickly advances from a backstage carny to a performer. After bedding Zeena the clairvoyant (Collette), he learns that her alcoholic husband Pete (David Strathairn) used to be a mentalist. Along with his natural skill for cold readings, Pete used an elaborate code of numbers and word signals he keeps hidden in a book. It’s worth a fortune, but it’s also capable of doing great harm. Ever the opportunist, Stan gets his hands on the book and plans to start a touring mentalist show with Molly (Mara), the virginal young performer he easily manipulates into love. Two years later, he and Molly play sold-out shows in Art Deco halls for posh audiences. But there’s a fine line between the intuitive skill of mentalism and a “spook show” in which Stan claims to converse with the dead—a line Zeena, Pete, and Molly warn him not to cross. Playing a medium and tampering with people’s lives carries the threat of Stan believing his own bullshit. “People are desperate to be seen,” Stan observes, and he fulfills that desire in his act. But when he pushes the performance beyond mere entertainment and into a spiritual con game, he takes a dark path.

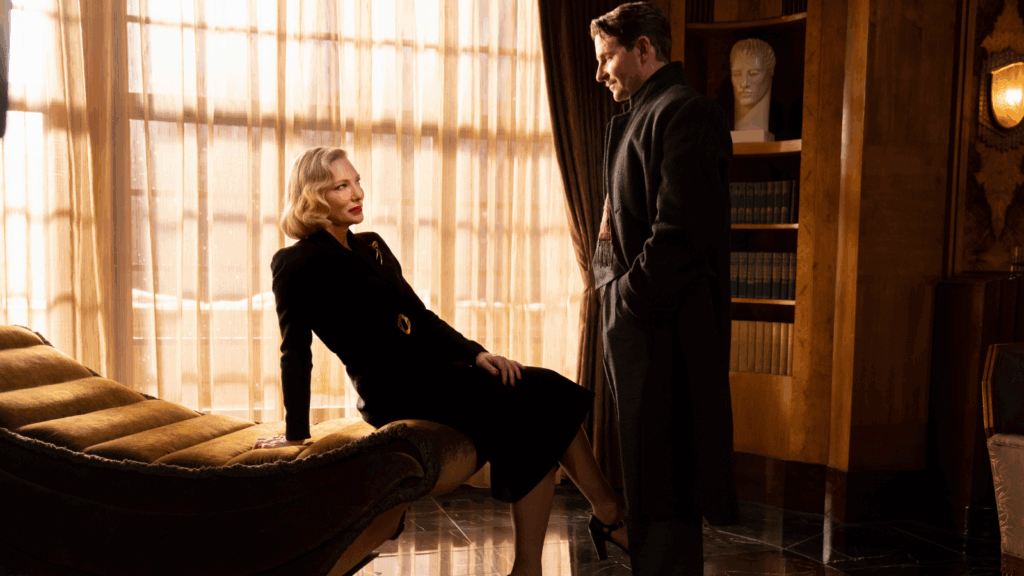

Cooper’s brilliantly internalized performance—haunted by dreams of Stan killing and burning his elderly father, a cruel drunk—follows the character on a relentless trajectory to fill the emptiness inside him. Having an angle and exploiting people on stage seems enough until he meets Lilith (Cate Blanchett), a psychologist who sees through his act. Together, they concoct a plan to dupe her well-to-do clientele out of their money, using information her patients shared in confidence. But first, she insists on some quid pro quo analysis, therein exposing Stan’s frailty. For instance, she cuts into his use of the word “never”—Stan defiantly says he “never” drinks and will “never” be like his father. But as many have observed, we’re doomed to become our parents. Stan may read others without much effort, but he fails to see himself clearly or know his limits. When Stan and Lilith target the powerful and dangerous businessman Ezra Grindle (Richard Jenkins), they intend to score thousands of dollars by Stan providing a spiritual conduit to Ezra’s dead lover. But any reader or viewer of noir knows that Lilith, smooth as silk and venomous as a viper, has other things on her mind when she kisses Stan after sipping whiskey. The taste of booze hangs on his lips, inciting him to gulp the glassful. At that moment, it’s as though she snaked a noose around his neck and released the trapped door.

Del Toro wasn’t the first to adapt Gresham’s novel. Edmund Goulding directed 20th Century Fox star Tyrone Power in a 1947 adaptation. While it’s appropriately noirish, classical Hollywood’s need for a happy ending stops short of stripping away the protagonist’s humanity and rendering him an unsalvageable geek. Del Toro’s version of Nightmare Alley hews closer to the book, following, in novelistic fashion, Stan’s gradual decline after making the mistake of believing his own lies. Some viewers might consider the film’s pacing slow, but it burns at an intentional pace rewarded by the final, chilling frames. The story’s setting in a distinctly seedy underbelly of post-Depression America shares much in common with countless film noirs. However, this isn’t the stuff of Venetian blinds, moody voiceovers, and high-contrast shadows; it’s about the downward spiral of the cruelly ambitious. While the film’s look may not evoke classical noirs (not yet, anyway; there’s a black-and-white version hitting some theaters in 2022), its outlook and dramatic structure are pure noir—plus, Lilith is an archetypal femme fatale, the climax is brutally violent, and the ending is achingly desolate.

Watching del Toro’s Nightmare Alley, the film that came to mind was Roman Polanski’s neo-noir Chinatown (1974). Both capture noir’s psychological and moral downswing while savoring meticulous period details in full living color (and stunning costumes here, provided by costume designer Luis Sequeira). Both feature a confident hero, morally corrupt but expert in his craft, who’s doomed to repeat a fatalistic cycle. For Jack Nicholson’s Jake Gittes, it was escaping apathy as a private eye to return once more to his former stomping grounds, only to be eviscerated by his new case. For Stanton Carlisle, it’s becoming the thing he hates most of all: his father. Fleshing out these themes, del Toro introduces images that underscore Stan’s existential dread—the most powerful of which remains a dead baby preserved in a jar. Kept by the carny Clem (Dafoe), the baby appears broken in half, kept together with Frankenstein stitching, and born with a pale third eye in its forehead. It’s a corrupted externalization of Stan—his self-image as a broken child unable to escape what his parents bore—so much so that he almost seems to recognize himself when he sees the thing in Clem’s tent.

Nightmare Alley is filled with grotesque yet symbolically loaded sights, but it also boasts a hypnotic atmosphere. The initial scenes where Stan steps off a bus and wanders around the carnival, where production designer Tamara Deverell has crafted a convincing world of smoke, mud, and glowing lights, prove transportive and magical. The production looks somehow dreamy and grimy at the same time, not the over-polished storybook quality of, say, Water for Elephants (2011). It’s an effect del Toro and cinematographer Dan Laustsen employed on The Shape of Water as well. Those who find themselves overloaded by visual details and textures may deem the film to be about surfaces. Still, Nightmare Alley doesn’t feel excessive or superficial, even while being an exceedingly beautiful dreamscape. Instead, it feels as though del Toro has applied a hint of expressive visuality onto the period-centric melodrama, capturing the past with a blend of truth and illusion—an effect that harmonizes with the story’s search for inner meaning. The performances, too, feel human, despite their embrace of genre tropes. Colette is sharp as Zeena, ever forward, down-to-earth, unfazed; Dafoe is casually insidious as the handler who shares how to reel in a drunk using alcohol, before he introduces the opium that will turn him into a geek; and this review hasn’t even mentioned Ron Perlman, Mary Steenburgen, Holt McCallany, or Tim Blake Nelson, all excellent.

Setting aside its thematic cohesion, Nightmare Alley is also a superb literary adaptation. Gresham’s book is a nasty piece of fiction, delightfully rancid with taboo subjects for 1946, including frank discussions of sexual predators, forced miscarriage, grifting, and homicide. Given that Gresham’s exploration of these themes came after his experiences in the Spanish Civil War, Nightmare Alley feels loosely connected to del Toro’s projects that assess the trauma of war with a touch of the fantastic. Even so, del Toro’s affinity for noir’s narrative conventions—from humanity’s descent to the mistrust of institutions—aligns effortlessly with his aesthetic. The film’s bleak assertion that mentalists, preachers, and shrinks all do the same trick becomes a faithless condemnation of those who consciously sell a bill of goods to those who need it. But as Lilith tells him, “You don’t fool people, Stan. They fool themselves.” It’s a stark reminder that, though our hero is such an expert that he can deceive a polygraph, he has less control and self-understanding than he thinks. Del Toro and Cooper bring to life the prevailing sense of Stan’s inner monster haunting him through the course of his downswing, mutating him into his fundamental self. By the film’s final shot, it might convince you that Nightmare Alley is the purest expression of del Toro’s career-long obsession with monsters.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review