Night of the Living Dead

By Brian Eggert |

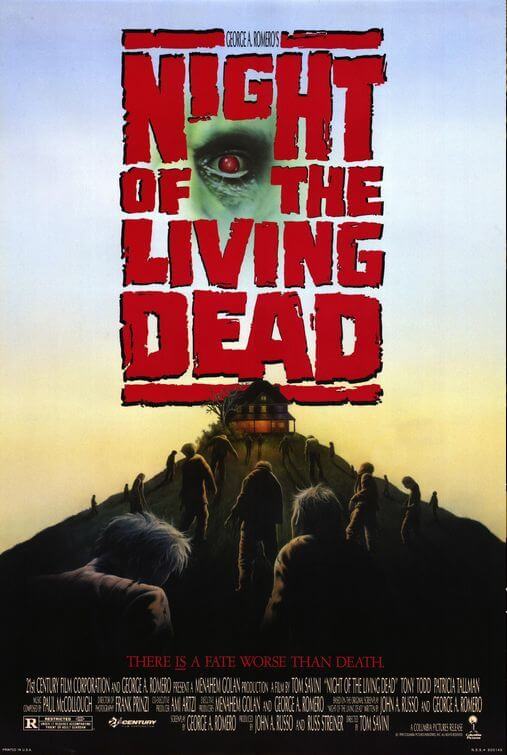

Remakes rarely stand up to their originals. A rare few prove superior to their source material, such as John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982) or David Cronenberg’s The Fly (1986). But most are entirely dismissed upon their release and then afterward forgotten as yet another failed attempt by Hollywood to exploit an intellectual property. The 1990 remake of George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead falls somewhere in-between. It delivers effective scares and bouts of credible acting, and its innovations on the original’s plot remain worthy changes. The sole reason it’s not better: Romero already told this story back in 1968 to iconic effect, and the remake remains diminished through our comparisons and familiarity with the material. Alongside longtime makeup FX artist and “King of Splatter” Tom Savini, who makes his directorial debut, Romero wrote and produced this underrated remake, which deserves a second look by today’s zombie-immersed culture.

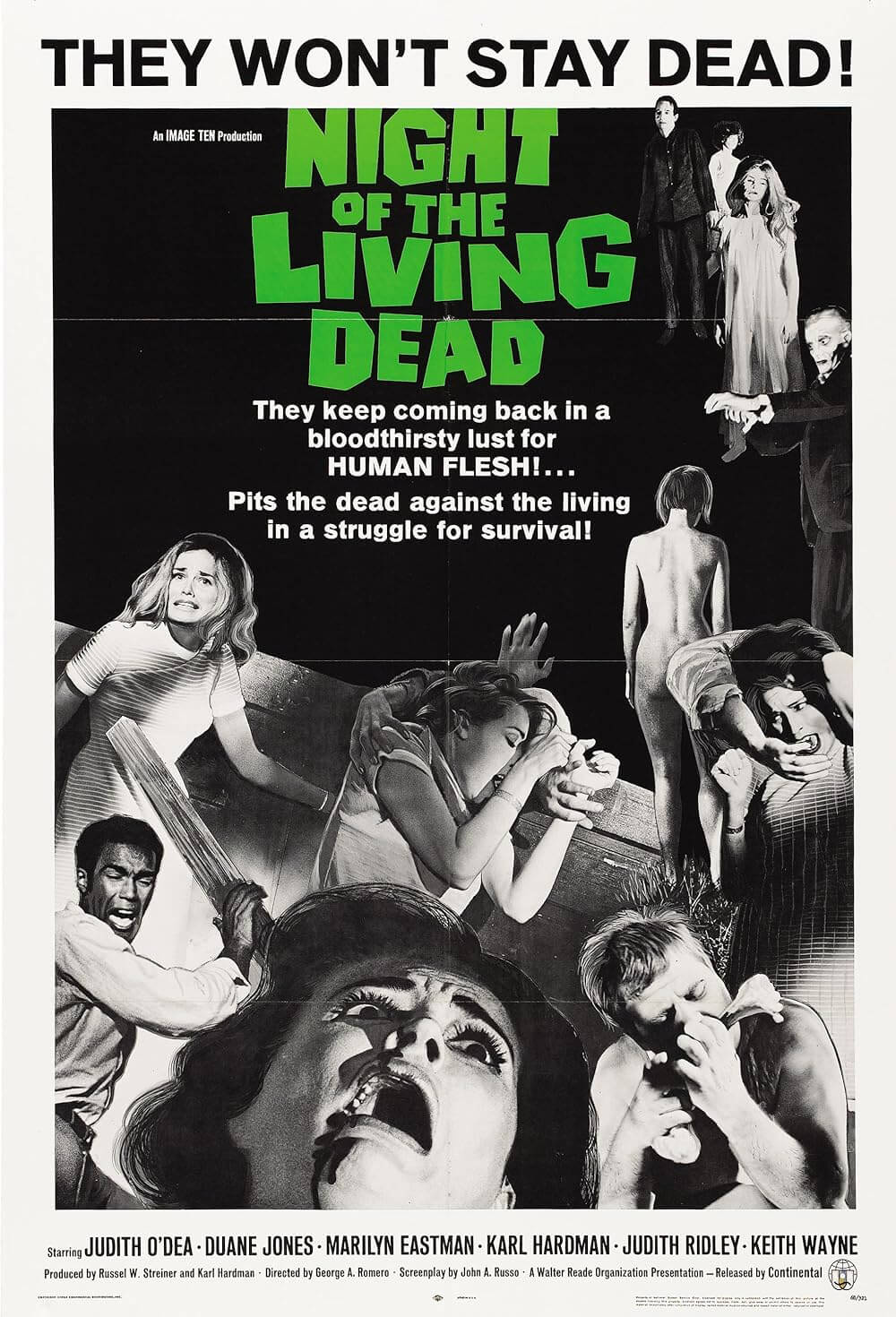

According to Bill Steigerwald’s article in the Los Angeles Times from 1990, Romero set out to produce a remake because of lingering rights issues associated with the original. Problems arose back in the late 1960s, when Romero’s distributors at Continental Releasing changed the film’s original title (“Night of the Flesh Eaters”) to Night of the Living Dead without securing the copyright, which meant the film languished in public domain, allowing untraceable bootlegs and unauthorized versions to appear in theaters. Meanwhile, because the distributors couldn’t track the duplications, Night of the Living Dead could have earned upwards of $50 million at box-office without the filmmakers seeing their due percentage of the profits. Romero’s production company, Image 10, tried to sue, but Continental went bankrupt before the filmmakers could collect on the $3 million judgment. In the coming years, the film appeared on television and home video, and later it was colorized. Only by jumping at a remake could Romero secure rights to the Night of the Living Dead namesake and finally earn a payday from the film for which he remains best known.

Shot for about $4.2 million, the remake was released in 1990, and print critics received it with marked disdain. Many cited Savini’s use of color as its downfall, preferring the original’s grainy, black-and-white photography shot in a cinema verité style. Roger Ebert wrote, “The remake is so close to the original that there is no reason to see both unless you want to prove to yourself that black and white photography is indeed more effective than color for this material.” Owen Gleiberman censured the use of color in a very ‘90s reference: “In the history of bad ideas… a color remake… has to rank up there with New Coke.” Any remake of a classic should expect such assessments, especially when the plot remains so closely tied to its source material. But even though the screenplay, written by Romero, closely follows the original’s, there are important distinctions that make some elements of Savini’s film, but not all, superior.

Shot for about $4.2 million, the remake was released in 1990, and print critics received it with marked disdain. Many cited Savini’s use of color as its downfall, preferring the original’s grainy, black-and-white photography shot in a cinema verité style. Roger Ebert wrote, “The remake is so close to the original that there is no reason to see both unless you want to prove to yourself that black and white photography is indeed more effective than color for this material.” Owen Gleiberman censured the use of color in a very ‘90s reference: “In the history of bad ideas… a color remake… has to rank up there with New Coke.” Any remake of a classic should expect such assessments, especially when the plot remains so closely tied to its source material. But even though the screenplay, written by Romero, closely follows the original’s, there are important distinctions that make some elements of Savini’s film, but not all, superior.

Savini’s “retelling” follows the basic plot outline of Romero’s original. The film opens with Barbara (Patricia Tallman) and her teasing brother Johnny (Bill Moseley) at the cemetery, where one of the flesh-hungry living dead interrupts their sibling spat. After watching Johnny die, Barbara runs and holes up in a nearby farmhouse, where realizes the dead are coming back to life. She’s soon joined by a stalwart hero, Ben (Tony Todd), as well as some local yokels. They all clash with the Cooper family, who have locked themselves in the farmhouse cellar. Just like the original, the cowardly Harry Cooper (Tom Towles) aggravates every scene, while his belittled wife (McKee Anderson) and sickly daughter (Heather Mazur) remain doormats. The survivors bicker and try to grapple with what’s happening around them, as their infighting tears them apart. Eventually, all goes south when they try to stage a daring gas pump run that ends in disaster.

Fortunately, Romero builds Barbara into a full-fledged character in the remake. Where in the original she suffered outdated notions of female hysteria, Barbara has been updated and seemingly modeled after Ripley from Aliens (1985). Of course, the original remains a breakthrough for featuring an African-American leading man in the midst of the Civil Rights movement, but it treated women as characters prone to catatonia and functionally useless within a tense situation. Romero and Savini correct that mistake in the 1990 version. A former stuntwoman, Tallman (who’s otherwise best known from a handful of appearances as various aliens on Star Trek: The Next Generation and Deep Space Nine) delivers a powerhouse performance—good enough to wonder why she didn’t get more acting work in subsequent years. The remake turns Barbara into a gun-toting badass who, while everyone else fearfully stays behind, resolves to abandon the farmhouse by herself, because she realizes zombies are slow and she can maneuver around them with little effort. Despite this progression, Romero balances out Cooper’s paranoia with Ben’s antagonistic attitude toward Cooper, which in turn reduces Ben to a character just as petty as Cooper.

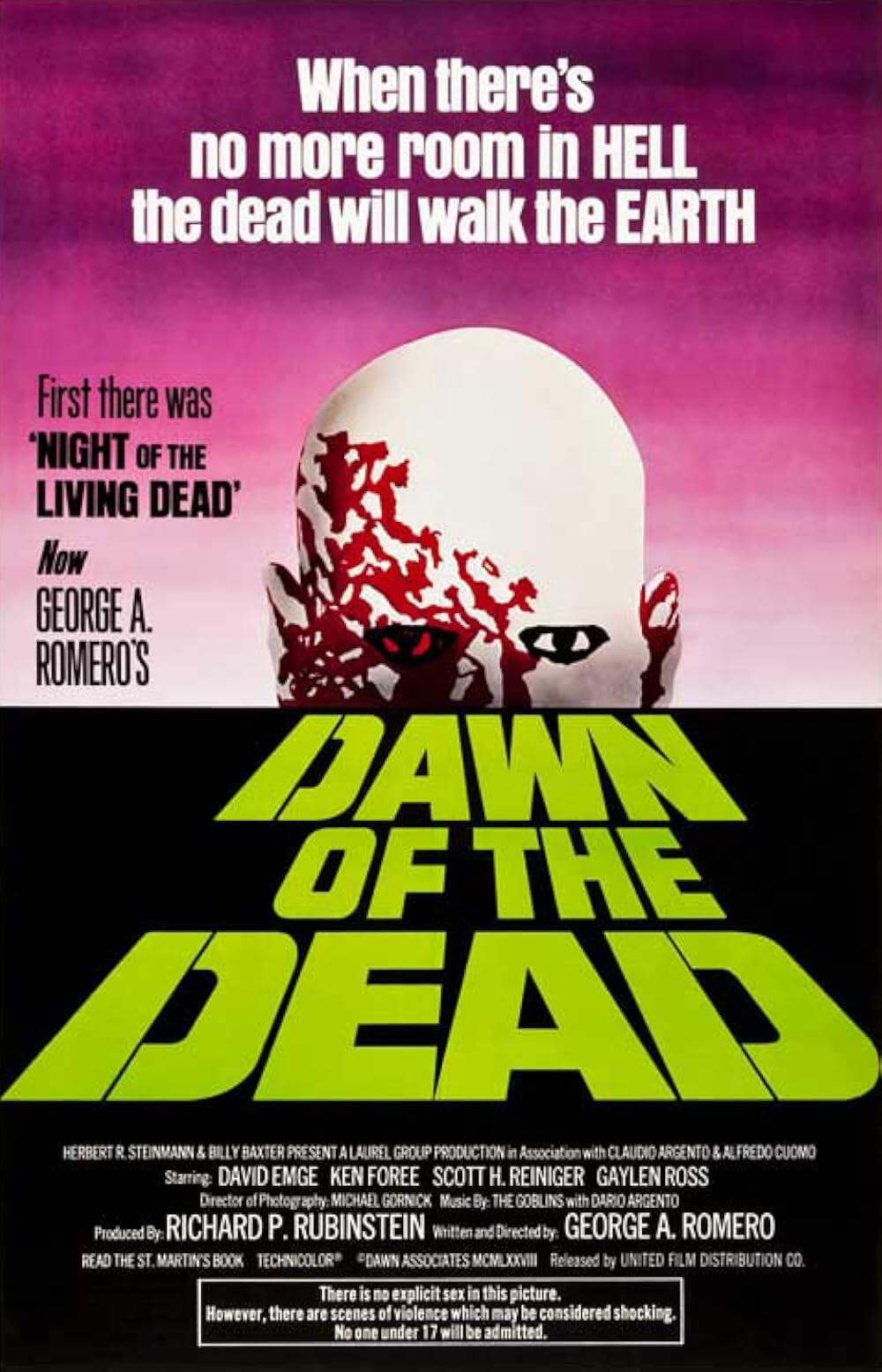

Aside from shooting in color, Savini also makes some unexpected choices in practical makeup. In the years following Romero’s original, zombie movies became less about social commentaries and metaphors than a testing ground for the limits of blood and gore. Even Romero’s of the Dead titles increased their yuck-factor, largely thanks to Savini’s expert makeup FX. Starting in the 1970s, Romero and Savini collaborated on a number of titles, including Dawn of the Dead (1978), Creepshow (1982), and Monkey Shines (1988). Their gory pinnacle was Day of the Dead (1985), which provided Savini with several chances to revile his audience. Meanwhile, Romero’s films had become cult favorites for a subculture of horror aficionados, Fangoria readers, and young filmmakers. Titles like Re-Animator (1985), The Return of the Living Dead (1985), and Return of the Living Dead Part II (1987) used horrifying makeup as their primary raison d’être.

Aside from shooting in color, Savini also makes some unexpected choices in practical makeup. In the years following Romero’s original, zombie movies became less about social commentaries and metaphors than a testing ground for the limits of blood and gore. Even Romero’s of the Dead titles increased their yuck-factor, largely thanks to Savini’s expert makeup FX. Starting in the 1970s, Romero and Savini collaborated on a number of titles, including Dawn of the Dead (1978), Creepshow (1982), and Monkey Shines (1988). Their gory pinnacle was Day of the Dead (1985), which provided Savini with several chances to revile his audience. Meanwhile, Romero’s films had become cult favorites for a subculture of horror aficionados, Fangoria readers, and young filmmakers. Titles like Re-Animator (1985), The Return of the Living Dead (1985), and Return of the Living Dead Part II (1987) used horrifying makeup as their primary raison d’être.

And yet, Savini’s film doesn’t continue the 1980s trend of increasing gore; rather, his film looks restrained next to standard 1980s zombie fare. Instead of cartoonish, sloppy makeup that splashes onto the screen, Steigerwald noted a “less-is-more approach, striving to make it as realistic as possible. They want the walking dead to look like somebody’s next-door neighbors, not mutant aliens.” To achieve this look, which is far removed from the previous decade’s zombie movies, Everett Burrell and John Vulich of the production’s makeup FX company Optic Nerve visited an autopsy, studied pathology textbooks, and even looked at Holocaust footage. The resulting zombies look like realistic corpses and carry believable injuries, as opposed to the blue-skinned zombies of Dawn of the Dead, the green-skinned animatronics in The Return of the Living Dead, or even the exaggerated Deadites from Sam Raimi’s The Evil Dead series. In this sense, Savini’s film calls back to Romero’s original ghouls.

One of the most memorable of these realistic looking zombies has been called “Truck Zombie,” because Ben runs him over with a pickup truck when he first speeds toward the farmhouse. Played by Dyrk Ashton, Truck Zombie saunters along, his skin flesh-colored and not yet rotted. All at once, Ben strikes him. The zombie’s lower half is broken and contorted, but his upper half remains active, his arms reaching for Ben, who finishes the creature off with a blow to the head. Ashton, who holds a Ph.D. in Film Studies and instructs at an Ohio university, recently shared his experiences filming the scene in an interview. “I got that gig because I knew the assistant director, Nick Mastandrea, and he recommended me to Tom,” said Ashton. “Tom himself actually called me out of the blue and asked if I wanted to be a zombie in the film. I got to choose Truck Zombie because it looked like the most fun.” Ashton went on to explain Savini’s crafty solution to filming the scene: “There was no stunt man. A dummy with my foam cast head was initially hit. Then we filmed me sliding down over the windshield and hood in reverse… For the broken body on the ground, I was standing in a hole with one of the effects artists down in there wiggling the fake back legs.”

Although the production exudes the ingenuity of a filmmaker accustomed to working with low budgets, what Savini’s remake doesn’t have is a discernible social or metaphoric motivations. Unlike Romero’s films, the zombies in the remake contain no overt symbolic purpose, such as being stand-ins for mindless consumers in Dawn of the Dead or metaphors for Americans who blindly trust their military in Day of the Dead. An argument could be made that racial tensions propel the story in the conflict between Ben and Cooper, but if that’s the intended case (which does not seem to be true), the commentary does not leap off the screen as Romero’s themes do elsewhere. A stronger argument might exists for a feminist reading through Barbara. Consider the scene where Ben, in a typical male act intended to establish himself as protector, tries to comfort Barbara by wrapping her in a jacket. Rather than accepting the Ben’s offer, the new Barbara wiggles out of the jacket; later, she changes from an impractical skirt to work boots and pants. Armed with a gun and a white tank top, she cannot help but resemble Sigourney Weaver’s Ellen Ripley.

Although the production exudes the ingenuity of a filmmaker accustomed to working with low budgets, what Savini’s remake doesn’t have is a discernible social or metaphoric motivations. Unlike Romero’s films, the zombies in the remake contain no overt symbolic purpose, such as being stand-ins for mindless consumers in Dawn of the Dead or metaphors for Americans who blindly trust their military in Day of the Dead. An argument could be made that racial tensions propel the story in the conflict between Ben and Cooper, but if that’s the intended case (which does not seem to be true), the commentary does not leap off the screen as Romero’s themes do elsewhere. A stronger argument might exists for a feminist reading through Barbara. Consider the scene where Ben, in a typical male act intended to establish himself as protector, tries to comfort Barbara by wrapping her in a jacket. Rather than accepting the Ben’s offer, the new Barbara wiggles out of the jacket; later, she changes from an impractical skirt to work boots and pants. Armed with a gun and a white tank top, she cannot help but resemble Sigourney Weaver’s Ellen Ripley.

Despite the film’s inspired improvements on the original, mostly centered on Barbara, Romero’s screenplay does not correct the forced antagonism between Ben and Cooper, which proves downright grating thanks to Cooper’s overwrought characterization (and moreover, he’s just a detestable character). Likewise, Romero also disposes of his original film’s significant, albeit indirect commentary on race, leaving Ben to feel ancillary and more like a plot device than a cultural reflector in the remake. These qualities give the Savini film an unevenness common among remakes, where the new release remains in the shadow of its predecessor. Still, Savini’s remake contains enough to set itself apart and deem the production worthy of revisitation. Approach the film less as a George A. Romero title than just a Tom Savini film, and Night of the Living Dead stands as a solid entry in the zombie subgenre.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review