Reader's Choice

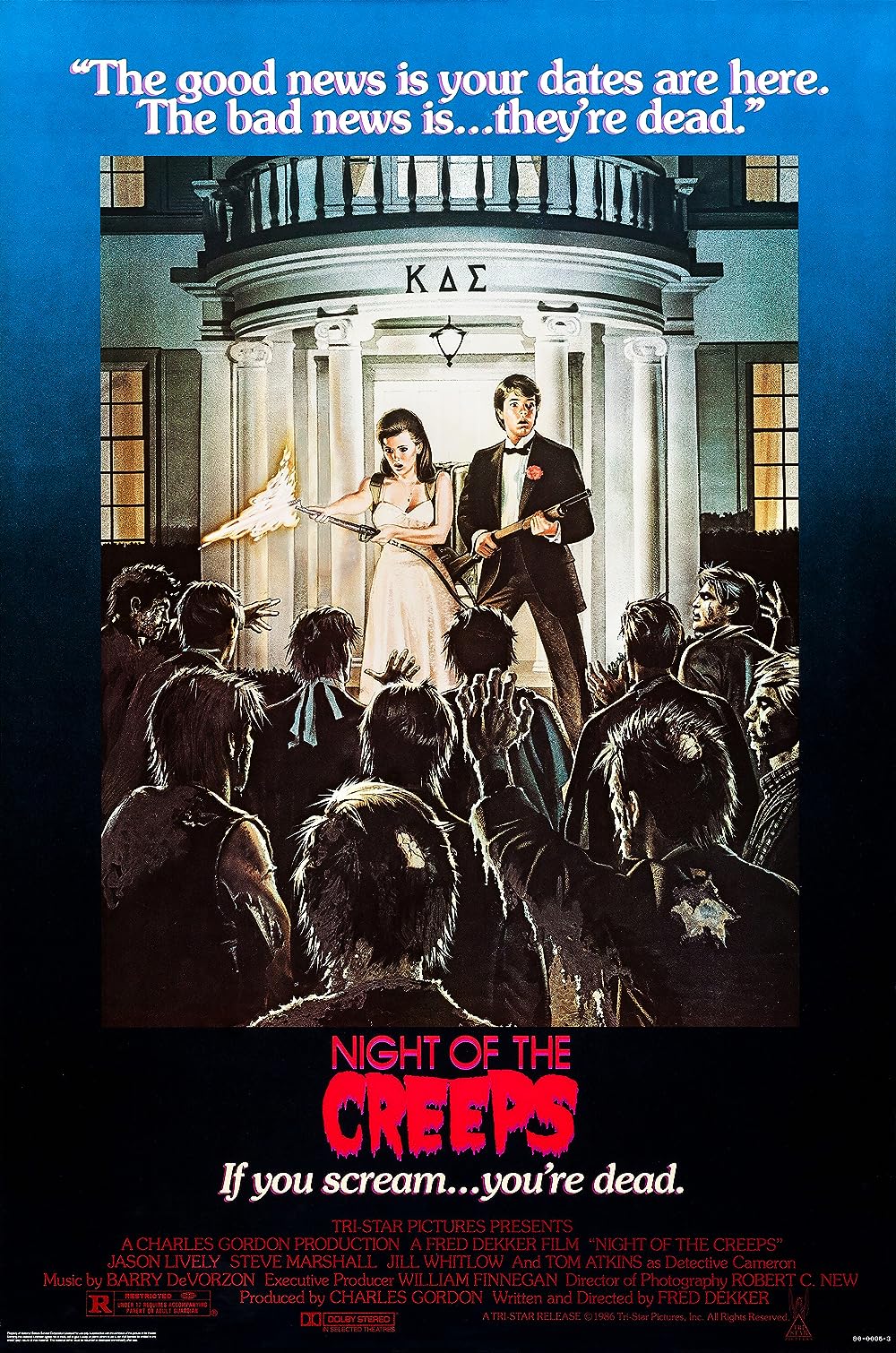

Night of the Creeps

By Brian Eggert |

Filled with creepy crawlies and even slimier elitist fratboys, Night of the Creeps plays genre mix-n-match with dizzying ambition. Slugs from outer space, a criminally insane axe-murderer, zombified corpses, a detective with a dark secret, elitist college douche bags, and a coming-of-age bromance—it all comes together in the 1987 debut of writer-director Fred Dekker. His freshman outing is far from pristine filmmaking, but it’s admirable in its scattershot momentum and the unexpected humanity of its characters. At one point, a television blares Plan 9 from Outer Space (1959), and while never so bad, Night of the Creeps proceeds with the same patchy, infectious passion as something by Ed Wood. Then again, this is no so-bad-it’s-good experience; rather, it’s a guiltless warts-and-all pleasure that becomes increasingly endearing, icky, and hilarious with each subsequent viewing. Dekker’s curious blend of science-fiction, bloody horror, and college comedy followed in the footsteps of John Landis (An American Werewolf in London, 1981) and Dan O’Bannon (The Return of the Living Dead, 1985), directors who explored the limitations of their favorite genres with an inspired wink at the audience. And though it originally bombed at the U.S. box office and went ignored by critics, the movie has since garnered a deserved cult following to which this writer firmly belongs.

Night of the Creeps reveals Dekker as a seasoned horror aficionado whose first few projects paid homage to his love of monster movies and comic book scenarios. Dekker attended UCLA’s English program at the same time as writer Shane Black (Lethal Weapon) was studying film. The two met and would collaborate several times over the years, first on Dekker’s sophomore effort, the cult favorite The Monster Squad (1987)—a riff on Spielbergian tropes and classic Universal Studios icons, where a bunch of kids team up with Frankenstein’s monster to stop Dracula, the Wolf Man, the Mummy, and the Creature from the Black Lagoon. Much later, Black and Dekker attempted to revive the Predator franchise with 2018’s The Predator. In the years between, Dekker punched up Hollywood scripts, directed an episode of HBO’s Tales from the Crypt, and drove the RoboCop franchise into the ground with RoboCop 3 (1993). He hasn’t had the most prolific or even successful career. But both Night of the Creeps and The Monster Squad remain landmarks for fans of knowing ‘80s genre fare, where the horror-comedy elements prove referential yet inspired. The cult around his work has formed with good reason—although it’s a reference machine, it’s also too quirky, hilarious, disgusting, downright weird, and wildly paced to dismiss. To be sure, the 88-minute runtime contains enough plot for several films.

In the first few minutes, Dekker explores three distinct genres. The movie opens on a ship in space, where two naked aliens of short stature chase after a third carrying a mysterious container (they all have the faces of Deadites from 1987’s Evil Dead 2). They speak alien, and we see two sets of subtitles—one in their unreadable language and another in parenthetical English. Why, you might wonder, did Dekker decide to include subtitles to a language we cannot speak? Is this supposed to be footage borrowed from other aliens who don’t speak the language of those shown onscreen? In any case, the alien running away from the other two jettisons its container into deep space. The scene must have taken place hundreds, if not thousands of years ago, because when the container finally reaches our planet, the setting changes to Sorority Row in 1959—a slice of collegiate Americana shot in black-and-white. This nostalgic, back-to-the-’50s setting finds two lovers, Johnny and Pam (Ken Heron and Alice Cadogan), driving after a falling star. But just like in The Blob (1958), the meteorite contains something else. It’s actually the alien container, and it’s filled with space slugs. One of them jumps into Johnny’s mouth in the woods, while back at the car, Pam finds herself chopped to bits by an escaped mental patient with an axe. If that’s not enough plotting to make your head spin, Dekker shifts the setting again, dropping the viewer into the middle of a Slobs vs. Snobs conflict worthy of Revenge of the Nerds (1984).

In the first few minutes, Dekker explores three distinct genres. The movie opens on a ship in space, where two naked aliens of short stature chase after a third carrying a mysterious container (they all have the faces of Deadites from 1987’s Evil Dead 2). They speak alien, and we see two sets of subtitles—one in their unreadable language and another in parenthetical English. Why, you might wonder, did Dekker decide to include subtitles to a language we cannot speak? Is this supposed to be footage borrowed from other aliens who don’t speak the language of those shown onscreen? In any case, the alien running away from the other two jettisons its container into deep space. The scene must have taken place hundreds, if not thousands of years ago, because when the container finally reaches our planet, the setting changes to Sorority Row in 1959—a slice of collegiate Americana shot in black-and-white. This nostalgic, back-to-the-’50s setting finds two lovers, Johnny and Pam (Ken Heron and Alice Cadogan), driving after a falling star. But just like in The Blob (1958), the meteorite contains something else. It’s actually the alien container, and it’s filled with space slugs. One of them jumps into Johnny’s mouth in the woods, while back at the car, Pam finds herself chopped to bits by an escaped mental patient with an axe. If that’s not enough plotting to make your head spin, Dekker shifts the setting again, dropping the viewer into the middle of a Slobs vs. Snobs conflict worthy of Revenge of the Nerds (1984).

This is where Night of the Creeps settles—pledge week 1986 at Corman University, with a “couple of bitchin’ guys on the prowl for some major-league babes.” The central bromance revolves around lovelorn Chris Romero (Jason Lively) and his encouraging friend J.C. (Steve Marshall), a fearless wiseacre on crutches. Chris has fallen in love with Cynthia Cronenberg (Jill Whitlow), but he’s shy and needs J.C.’s encouragement to approach her. He convinces himself that Cynthia won’t look at him unless he joins a fraternity. So they present themselves to Beta Epsilon president The Bradster (Allan Kayser) and his fellow fratboys who, based on their mustaches and receding hairlines, have been in college for about fifteen years. They have no intention of allowing these twerpy pledges into their pompous ranks. But Brad, who happens to be dating Cynthia, tasks Chris and J.C. with stealing a corpse from the university facilities and dropping the cadaver on a sorority house steps in a crude prank. When the two friends find a “corpsicle” in a cryogenic lab, they unknowingly thaw out Johnny from the earlier 1950s sequence. And while Johnny appears dead, the alien slugs writhing around in his brain keep him animated, sauntering around like a zombie. Chris and J.C. witness his movement before running away back to their dorm, terrified.

Already you notice a pattern. Dekker has named every character after a well-known horror director—J.C. stands for James Carpenter-Hooper, making an association between Christ and the holiest of horror directors. The references will continue to conspicuous effect. Though, Dekker’s screenplay does not subsist on nods to past horror movies alone; he offers memorable characters and humor to match. Chris and J.C. have an affecting, genuine friendship in which saying “I love you” to one another is acceptable. J.C. is particularly endearing in his desire to help Chris be happy, despite his friend’s constant whining and fear of talking to Cynthia. In one speech, J.C., ever the wise-cracker, breaks his positive streak out of frustration with Chris’ fear and sense of defeat. The scene might suggest that J.C. is secretly occupying the gay best friend trope; the ensuing homoerotic “you wish” remarks, followed by a pillow fight, certainly supports this reading. But Dekker’s script moves too fast for subtext. What’s on the surface, however, proves surprisingly painful when J.C. inevitably becomes prey to space slugs that lay eggs in their victim’s brain. At this point, the victim becomes a zombie-like drone until their head splits in a gooey outpouring of slimy creatures. Realizing his fate, J.C. leaves Chris a tape-recorded goodbye that hurts. Less endearing is Cynthia, a character written to be desirable, quiet, hesitant, and passive—until she straps on a flame thrower for the final sequence.

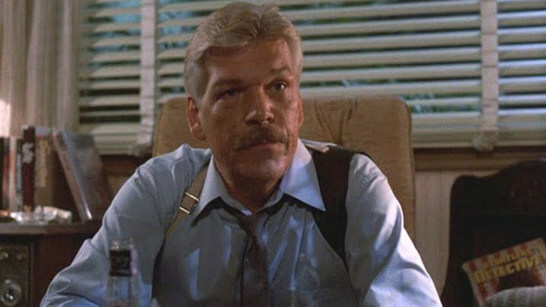

Before then, Dekker introduces Detective Ray Cameron, played by Tom Atkins, a cult actor who owes his most beloved character to Night of the Creeps. Atkins appeared in cop roles on television’s The Rockford Files and Serpico before taking small parts in John Carpenter’s The Fog (1980) and Escape from New York (1981), then Romero’s Creepshow (1982). When Carpenter served as producer on the unfairly maligned Halloween III: Season of the Witch (1982), he cast Atkins as the unlikely star, a womanizing doctor on the trail of a pagan conspiracy. Here, Dekker has written Cameron as a gruff cop who borrowed his lifestyle from a Dashiel Hammet detective novel. “Do you get off on living in the past?” a fellow officer asks him. One look at Cameron’s vintage police car and raincoat, or how Dekker shoots his scuzzy apartment from above through a ceiling fan, and it’s apparent that he does. “Thrill me,” says Cameron when he picks up his phone, a line that signals his cynical seen-it-all worldview. The next day or so puts him on the trail of Chris and J.C., trying to make sense of a case that involves “zombies, exploding heads, creepy-crawlies, and a date for the formal.” Regardless of Cameron’s corny humor (“What is this? A homicide or a bad B-movie?” he remarks in the ransacked cryogenics lab), Dekker reveals a dark subplot about the tragedy that defines this self-destructive cop.

Before then, Dekker introduces Detective Ray Cameron, played by Tom Atkins, a cult actor who owes his most beloved character to Night of the Creeps. Atkins appeared in cop roles on television’s The Rockford Files and Serpico before taking small parts in John Carpenter’s The Fog (1980) and Escape from New York (1981), then Romero’s Creepshow (1982). When Carpenter served as producer on the unfairly maligned Halloween III: Season of the Witch (1982), he cast Atkins as the unlikely star, a womanizing doctor on the trail of a pagan conspiracy. Here, Dekker has written Cameron as a gruff cop who borrowed his lifestyle from a Dashiel Hammet detective novel. “Do you get off on living in the past?” a fellow officer asks him. One look at Cameron’s vintage police car and raincoat, or how Dekker shoots his scuzzy apartment from above through a ceiling fan, and it’s apparent that he does. “Thrill me,” says Cameron when he picks up his phone, a line that signals his cynical seen-it-all worldview. The next day or so puts him on the trail of Chris and J.C., trying to make sense of a case that involves “zombies, exploding heads, creepy-crawlies, and a date for the formal.” Regardless of Cameron’s corny humor (“What is this? A homicide or a bad B-movie?” he remarks in the ransacked cryogenics lab), Dekker reveals a dark subplot about the tragedy that defines this self-destructive cop.

Back in the 1950s timeline, Cameron, a heartbroken rookie cop dumped by Pam, finds his ex hacked to pieces by the escaped psychopath. Cameron snapped, hunted down the deranged killer, and took justice into his own hands. He buried the killer’s body in a then-vacant lot behind Pam’s sorority; in the 1980s timeline, Cynthia lives in the same sorority house, and the vacant lot has since been developed to include a house mother’s cottage. The trauma of Cameron’s sweetheart dying in such a brutal way, combined with his murderous revenge, is reawakened when Cameron sees several corpses with heads split open as if by an axe. He doesn’t believe the wild stories told to him by Chris and J.C. about brain-eating slugs at first—not until the corpse of the 27-years-gone axe-murderer emerges from the ground and kills again. Atkins pairs his unhinged qualities with a disarming pathos, especially when, after he once again confronts the murderer of his first love, he plans to kill himself with oven gas and a lighter. Fortunately, Chris interrupts the attempt and enlists Cameron for the showdown between our heroes and a swarm of space slugs inside zombified creeps.

The climactic sequence finds The Bradster and his slug-infested fratboys invading Cynthia’s sorority house on the night of a school formal. “I got good news and bad news, girls,” Cameron announces to the sorority. “The good news, your dates are here. The bad news, they’re dead.” It’s a line so perfect, the marketing wizards at TriStar Pictures used it on the poster. Meanwhile, Chris, armed with a shotgun, and Cynthia, lugging a flamethrower, dispose of the slugs and their hosts in a barrage of bloody, splattery special FX. Inside, Cameron goes berzerk with his revolver, then a can of hair spray and a lighter. But for every yucky practical effect, there’s a lighthearted quip to balance the thrills. “It’s Miller time!” Cameron bellows before emptying his chambers on the walking corpses. The finale culminates when Cynthia thinks to tell Chris about the science project stored in the sorority’s basement, marking the first and only use of Chekov’s box of jarred brains. These last ten minutes of Night of the Creeps remain an exuberant display of gross-out effects and comic timing that would be impressive for a seasoned horror filmmaker, even more so for the untested Dekker, who reportedly wrote the script in a week.

Night of the Creeps is filled with unrefined ideas and delirious progressions, and the seams reveal themselves upon close inspection. Why does a space slug embed itself in the brain of an axe-murderer who has been wrapped in plastic and buried for almost three decades, when it could have just invaded any number of college students? It’s a convenient storytelling device, though not exactly tight screenwriting. Moreover, given the movie’s partial status as ‘80s college fare, there’s also an exploitative male gaze at work, with cinematographer Robert New panning across topless coeds in the shower or lingering as Cynthia changes into a nightgown. One also cringes at the stereotypical Asian janitor who repeatedly laughs to himself, “Screaming like banshees.” Fortunately, such awkward asides remain few, allowing the viewer to savor the more cherishable moments. When Cameron and Chris visit the police station armory to check out a flamethrower, the cameo with genre veteran Dick Miller is priceless. I also love the interaction between J.C. and Steve, a dim-witted jock with a unibrow. Finally, the ending in the Director’s Cut proves superior with the aliens’ return, searching a nearby cemetery for their missing slugs.

Night of the Creeps is filled with unrefined ideas and delirious progressions, and the seams reveal themselves upon close inspection. Why does a space slug embed itself in the brain of an axe-murderer who has been wrapped in plastic and buried for almost three decades, when it could have just invaded any number of college students? It’s a convenient storytelling device, though not exactly tight screenwriting. Moreover, given the movie’s partial status as ‘80s college fare, there’s also an exploitative male gaze at work, with cinematographer Robert New panning across topless coeds in the shower or lingering as Cynthia changes into a nightgown. One also cringes at the stereotypical Asian janitor who repeatedly laughs to himself, “Screaming like banshees.” Fortunately, such awkward asides remain few, allowing the viewer to savor the more cherishable moments. When Cameron and Chris visit the police station armory to check out a flamethrower, the cameo with genre veteran Dick Miller is priceless. I also love the interaction between J.C. and Steve, a dim-witted jock with a unibrow. Finally, the ending in the Director’s Cut proves superior with the aliens’ return, searching a nearby cemetery for their missing slugs.

Night of the Creeps is propelled by its sheer energy and love of its genres. Dekker’s post-modern appreciation feels like a warm blanket to those who, like him, grew up on a diet of creature features and college comedies. He crams every impulse into a movie that feels both hastily assembled yet oddly cohesive, given all the moving parts. Along with David Cronenberg’s Shivers (1973), it helped inspire James Gunn’s Slither (2006) with its exploitative ‘80s schlockfest quality. Blood, gore, and various monsters aside, the most impressive flourish is how Dekker earns our empathy for his likable main cast. To be sure, the movie is a personal favorite—the sort of movie that I’ve watched countless times and accept its many flaws, in the same way that J.C. overlooks Chris’ character defects. Sure, watching it from a critical perspective, you notice plot holes, leaps in story logic, unexplained details, and occasionally the literal strings (which pull the slugs across the floor, wriggling with an awful speed and squirmy sound effect, which gives me the willies). But Dekker’s enthusiasm behind the camera renders the flaws throughout Night of the Creeps negligible, making them part of the movie’s enduring charm.

(Editor’s Note: This review was suggested and commissioned on Patreon. Thanks for your support, Brenda!)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review