Night Moves

By Brian Eggert |

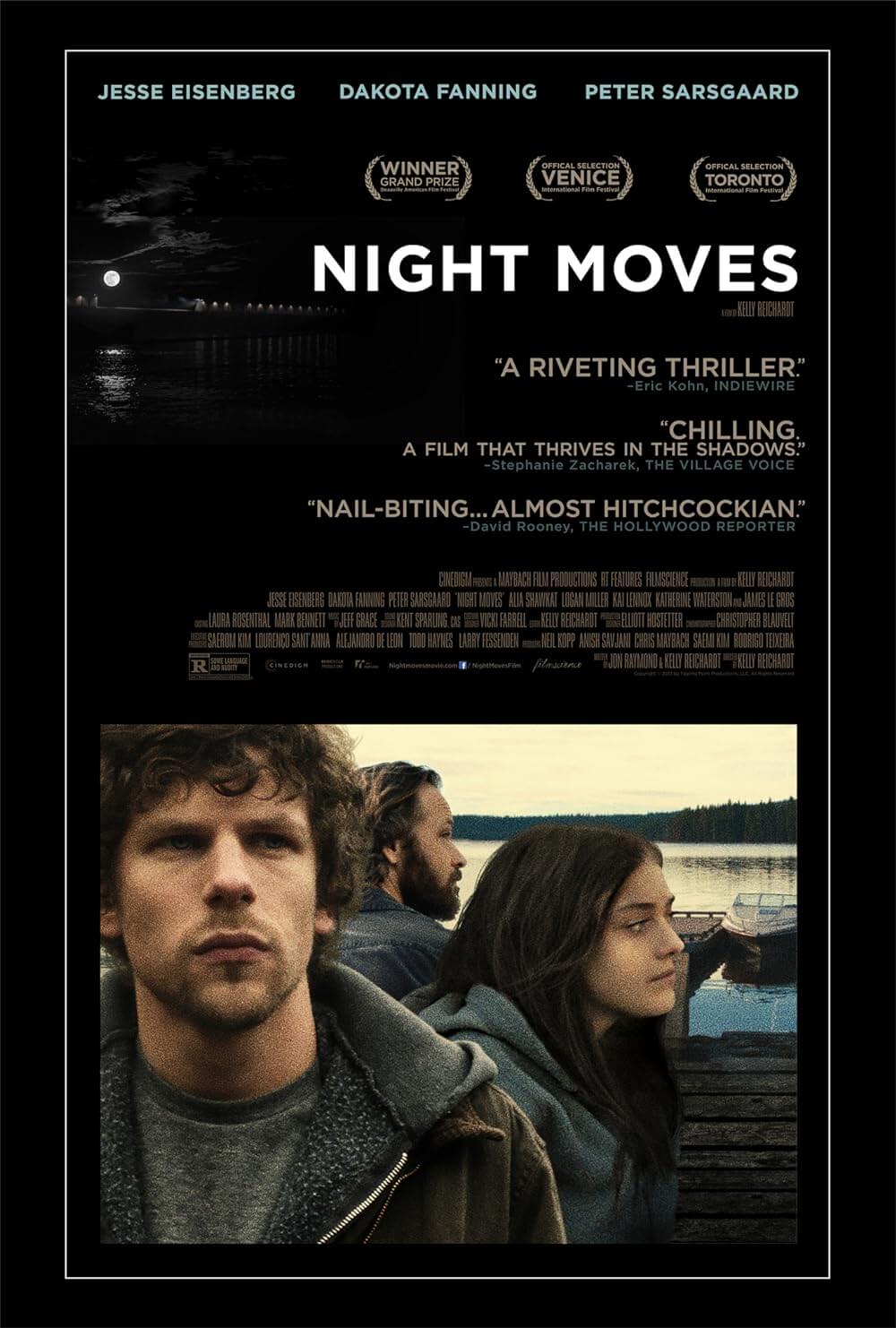

In the first scenes of Night Moves, Josh, an eco-militant played by Jesse Eisenberg, finds a bird’s nest on the forest floor and gently returns it to the tree from where it fell. Josh wants to repair Nature from the influence of human beings, but his next act won’t be so delicate; it will involve a hydroelectric dam and a bomb made of fertilizer. Kelly Reichardt’s 2013 film adopts the conventions of a thriller, complete with criminal plans, the fear of capture, and later, the threat of murder. It contains elaborate and almost conspiratorial schemes, personal betrayals, and actions driven by personal conscience. They’re familiar themes in the subgenre of 1970s thrillers such as Roman Polanski’s Chinatown (1974) or even Arthur Penn’s same-named Night Moves (1975)—films about water, conspiracy, and observation. How fitting that the story unfolds in the Pacific Northwest, the location of most Reichardt films, where an ongoing debate over environmental preservation has played out in both local law and national politics. Regardless of how familiar its themes may appear, Reichardt’s Night Moves serves as a rarity in her body of work, even as it has more in common with her auteurist voice than a first glance suggests.

Reichardt co-wrote the screenplay alongside her regular collaborator, author Jonathan Raymond, telling an original story about three eco-terrorists plotting to blow up a dam on the Oregon river. It’s another of her films—after River of Grass (1994), Old Joy (2006), Wendy and Lucy (2008), and Meek’s Cutoff (2010)—interested in people who live on the margins of conventional society. Josh, Dena (Dakota Fanning), and their ex-Marine compatriot named Harmon (Peter Sarsgaard) have an idealistic plan to shake the public out of their apathy with a demonstration. Other local activists who don’t believe in “one big plan” but “a lot of small plans” only frustrate Josh, who hopes to compel a broader public discussion about environmental health. “People are gonna start thinking,” says Josh, “they have to.” The specific reasons for the trio’s plan remain a vaguely articulated series of remarks about the dangerous impact of humanity on Nature, the selfishness of “killing all the salmon just so you can run your fucking iPod every second of your life.” But then, Reichardt is less interested in exploring environmental issues than the moral dynamics of her characters—familiar types for the director: people who exist outside of normalized social systems, feel at odds with the world, and subsist in a limbo-like state.

Josh lives in a yurt on an organic farm; Dena works at a New Age women’s spa; Harmon lives in a trailer on an isolated spot of land deep in the woods. They attend loosely organized meetings where other environmentally conscious locals watch ineffectual documentaries and talk about making an ecological impact. However, even in their like-minded community, Josh, Dena, and Harmon are outsiders. When they first meet, their plan has already been laid out, and the audience must observe each step as it progresses. Reichardt films rarely contain a lot of dialogue or exposition, leaving the viewer to glean details from her close observation of their actions. And along with the severe, restrained performance by Eisenberg, who internalizes every emotion, Reichardt conjures a staggering amount of suspense in this closely watched criminal procedural. Even so, she doesn’t omit personal anxieties between the three conspirators; there’s sexual tension between them that emerges in a scene where Josh hears Dena and Harmon together. Such moments serve the characters, however, not the plot.

The first half of Night Moves dwells on the progress of their clandestine operation, using masterfully calibrated scenes of reserved action. In one sequence, Josh and Dena visit a suburban home to buy a boat (called Night Moves no less) with cash, and Josh’s impersonal behavior becomes a point of tension; in contrast, Dena appears more charismatic and able to manipulate the seller into believing they’re normal people. Perhaps that’s why the group chooses her for their next task, buying 500 pounds of ammonium nitrate fertilizer to augment the explosive payload. It’s a tense sequence where Dena must interact with a suspicious store manager (James Le Gros), who demands her Social Security card to complete the purchase. After they acquire their supplies and load the boat, Reichardt ratchets the anxiety with the threat of exposure. There’s a tense scene with a jabberjaw who appears at their campsite to talk about his “wild times” back in the ‘80s, and the three do little to disguise their disdain for his presence. Later that night, as they attach their bomb to the dam, they realize that a car parked nearby may thwart their whole plan, while Reichardt, serving as editor, cuts back-and-forth between the characters and the red digital countdown.

The first half of Night Moves dwells on the progress of their clandestine operation, using masterfully calibrated scenes of reserved action. In one sequence, Josh and Dena visit a suburban home to buy a boat (called Night Moves no less) with cash, and Josh’s impersonal behavior becomes a point of tension; in contrast, Dena appears more charismatic and able to manipulate the seller into believing they’re normal people. Perhaps that’s why the group chooses her for their next task, buying 500 pounds of ammonium nitrate fertilizer to augment the explosive payload. It’s a tense sequence where Dena must interact with a suspicious store manager (James Le Gros), who demands her Social Security card to complete the purchase. After they acquire their supplies and load the boat, Reichardt ratchets the anxiety with the threat of exposure. There’s a tense scene with a jabberjaw who appears at their campsite to talk about his “wild times” back in the ‘80s, and the three do little to disguise their disdain for his presence. Later that night, as they attach their bomb to the dam, they realize that a car parked nearby may thwart their whole plan, while Reichardt, serving as editor, cuts back-and-forth between the characters and the red digital countdown.

Reichardt’s application of suspense is downright Hitchcockian, complete with the audience’s awareness of a bomb wired to blow. But Hitchcock often created suspense with the threat of a bomb and the explosive result, as in Sabotage (1936), when he follows a small boy carrying a wired film can through London and then watches him detonate. Reichardt, though, proves more subtle; she doesn’t show the explosion. When the bomb goes off, we hear only a faint sound in the distance as the camera rests on the relieved faces of her eco-terrorists. Her suspense is purely psychological. Reichardt is not concerned with action itself but how her characters work through and process the outcome of the action. It’s a quality evident when they try to leave the scene of the crime, but their truck fails to turn over on the first attempt, recalling a similar moment from Double Indemnity (1944). In the aftermath, Night Moves generates suspense out of suspicion and guilt. Though the bomb was supposed to destabilize “the grid” and hurt no one, a bystander unexpectedly died downriver. Dena’s nerves begin to fray. She’s plagued with questions of morality and culpability; she breaks out in hives, and she starts talking. All at once, the film becomes a noirish story about Josh trying to cover his tracks.

What makes their act all the more pointless is that none of it will have any bearing on the health of the environment, nor have they destabilized the status quo. A farmer points out, “That river has like twelve dams on it,” then calls the bombing mere “theater.” Josh and company have accomplished nothing, raised no greater issues with the general public, and instead have exacerbated an alarming element of today’s society: the modern world’s obsession with bureaucratic systems of surveillance. This might be Reichardt’s true target with Night Moves. What happens when there are no more natural spaces untouched by humanity? What are the implications of society’s prying eyes that continuously record everything? When Harmon admits to having a criminal past but claims his record was expunged, Dena argues that records are never lost, they’re just that—a record. “The grid is everywhere” as another character notes. It’s the final thought Reichardt leaves us with, as Josh, who has left town to disappear and start over, must fill out a job application. Except, he has no address or information to supply. The haunting final shot suggests that Josh’s mission was doomed from the start, and in a way, we cannot help but empathize with his sense of imprisonment.

Shot by cinematographer Christopher Blauvelt with impressive clarity to the night scenes and weight to the mostly outdoor settings, Night Moves is an austere and beautifully composed film, marked by three excellent and nuanced performances at the center. On the surface, it’s a thriller that bears little resemblance to Reichardt’s other films and could be reduced to a simple logline. But underneath its seemingly conventional surface lies a debate about radicalism, morality, and a critique of our surveillance-obsessed age. Reichardt seems to agree with the general environmental, righteous concerns of her protagonists, even as she exposes their methods as hollow and meaningless in a society utterly wired into the grid. She hasn’t made a soapbox for their ideology, nor has she helped write a screenplay laden with political speeches or rhetoric. Reichardt creates something far more effective in the film’s lasting sense of uneasy tension, which fills the viewer with anxiety about our world that lingers long after the final frame.

Bibliography:

Fusco, Katherine, and Nicole Seymour. Kelly Reichardt – Contemporary Film Directors. University of Illinois Press, 2017.

Hall, E. Dawn. ReFocus: The Films of Kelly Reichardt. Edinburgh University Press, 2018.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review