Nickel Boys

By Brian Eggert |

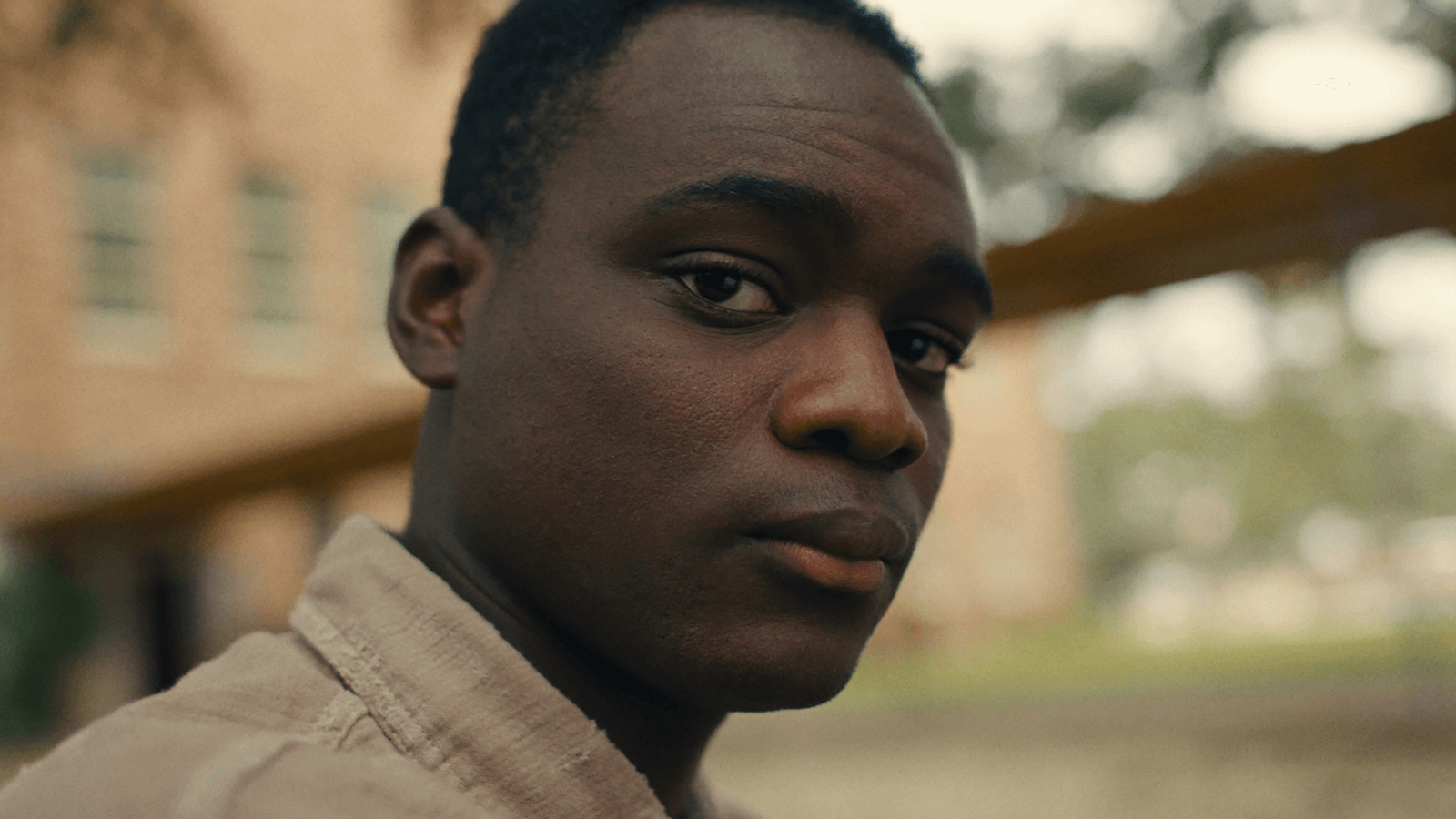

Nickel Boys takes place in the Jim Crow South, where its two central characters have been detained inside a so-called reform school, Nickel Academy, modeled on Florida’s real-life Dozier Academy. Over 100 deaths occurred there, predominantly from the horrific abuse and murder of Black students. The events in the story happened not so long ago, in the 1960s. Director RaMell Ross and his editor, Nicholas Monsour, occasionally cut away from the scenes at Nickel Academy to remind the viewer what was happening in the world when such targeted racial violence struck the Tallahassee juvenile detention center. Iconic moments from the Civil Rights Movement appear in newsreel-style cutaways, from Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Selma to Montgomery march to news about desegregation. But more jolting is footage from the space race. While most of the United States followed the country’s forward-thinking leap into the future by beating the Soviets to the lunar surface, an unthinkably cruel and decidedly backward form of punishment was occurring in Florida, the same state where Apollo 11 took off from Cape Kennedy.

The first part of Nickel Boys follows Elwood, played by Ethan Herisse, who’s raised by his kindly grandmother (Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor). Elwood is full of promise; he plans to attend community college, but a wrong-place, wrong-time situation lands him unjustly in Nickel Academy. He meets Turner (Brandon Wilson) there, and the two bond over their marginalization. While the white kids play football and receive better treatment, students of color must respond to officials with “Yessir” and have only two minutes to shower. When his grandmother visits, the school’s management tells her Elwood cannot have visitors. Punishments include isolation in a rooftop hotbox, physical beatings, and torture, all of which cause students to perish. When that happens, they’re labeled a runaway and buried in an unmarked grave. Later, the film shifts to Turner’s perspective, and later still, to one of them as an adult (Daveed Diggs), recalling his experiences at the academy and uncovering evidence of the atrocities performed there.

Based on the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel from 2019 by Colson Whitehead, Ross and co-writer Joslyn Barnes’ adaptation occupies a space between period drama and experimental cinema. Yet, the film stands on an accessible medium ground. It’s the kind of filmmaking that earns the overused term “tone poem,” with its impressionistic editing and distinct, albeit loose formal agenda. Best known for his 2018 documentary Hale County This Morning, This Evening, Ross has produced photographs and installations that have been shown in museums. He takes a similarly artistic approach to his first dramatic feature, deploying a technique that seldom feels like a straightforward drama with its leapfrogging through time and blending archival footage and expressive shots into the mix. Captured almost entirely from a first-person perspective and in a 4:3 aspect ratio, Nickel Boys is one of the most formally experimental films released by a major studio in recent memory.

Ross and cinematographer Jomo Fray visualize the Black experience through point-of-view shots, capturing the events that befall Elwood and Turner with an entrenched subjective eye. Besides witnessing the horrors of Nickel Academy in a veritable first-hand manner, Nickel Boys also finds countless beautiful details accumulated not only through their eyes but stored in their minds. Shots of goosebumps on an arm, looking up from the floor at a Christmas tree, or a reflection in a shop window convey Ross’ interest not only in an exposé of racist reform schools but also in memory and time. It’s a Malickian flourish, searching and lyrical, albeit without a strict set of rules. While many shots occupy a character’s POV, others do not. At several points in the film, a shot may have no subjectivity and instead communicates dramatic information. These moments are rare, but when they occur, they break up the rhythms established by the camerawork, sometimes to distracting effect.

Watching Ross’ film, I found myself trying to crack the aesthetic code or understand its rulebook. But Nickel Boys is more free-flowing than that. While much of the presentation occupies a subjective perspective, other sequences have haunting poetry—from black-and-white images to a time-lapse sequence inside a train car. The narrative structure resists a traditional linear path, as though every image represents a memory, and the memories have come flooding back. It might be tempting to assign the film to the character played by Diggs from decades later, but even his scenes take a unique approach. He’s shown from behind, a camera mounted on his torso, following him from an intentional, disembodied distance. Similarly, the score by Alex Somers and Scott Alario feels less like manipulative period drama music than uncanny sounds that echo in Elwood and Turner’s heads with haunting resonance.

All of the film’s many conceptual stylistic touches may be what distinguish Nickel Boys as something exceptional, even while they may prevent less adventurous moviegoers from connecting to its dramatic core. Admittedly, the film’s constantly shifting formal modes at once drew my attention away from the story and yet, strangely, brought me closer to the characters. This ever-present push and pull makes for engaging cinema nonetheless, while also underscoring its relationship to contemporary sociopolitical conditions in America. Turner explains the grim reality of bigotry in their school, where “no one has to act fake anymore.” The same is true today, as the rise of unhindered racism runs rampant among some figures of authority and their supporters. So, while Nickel Boys remembers a tragic and disturbing past, it also presents a warning: if those in power remain unchecked, such evils could happen again.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review