Never Let Me Go

By dfrmaster |

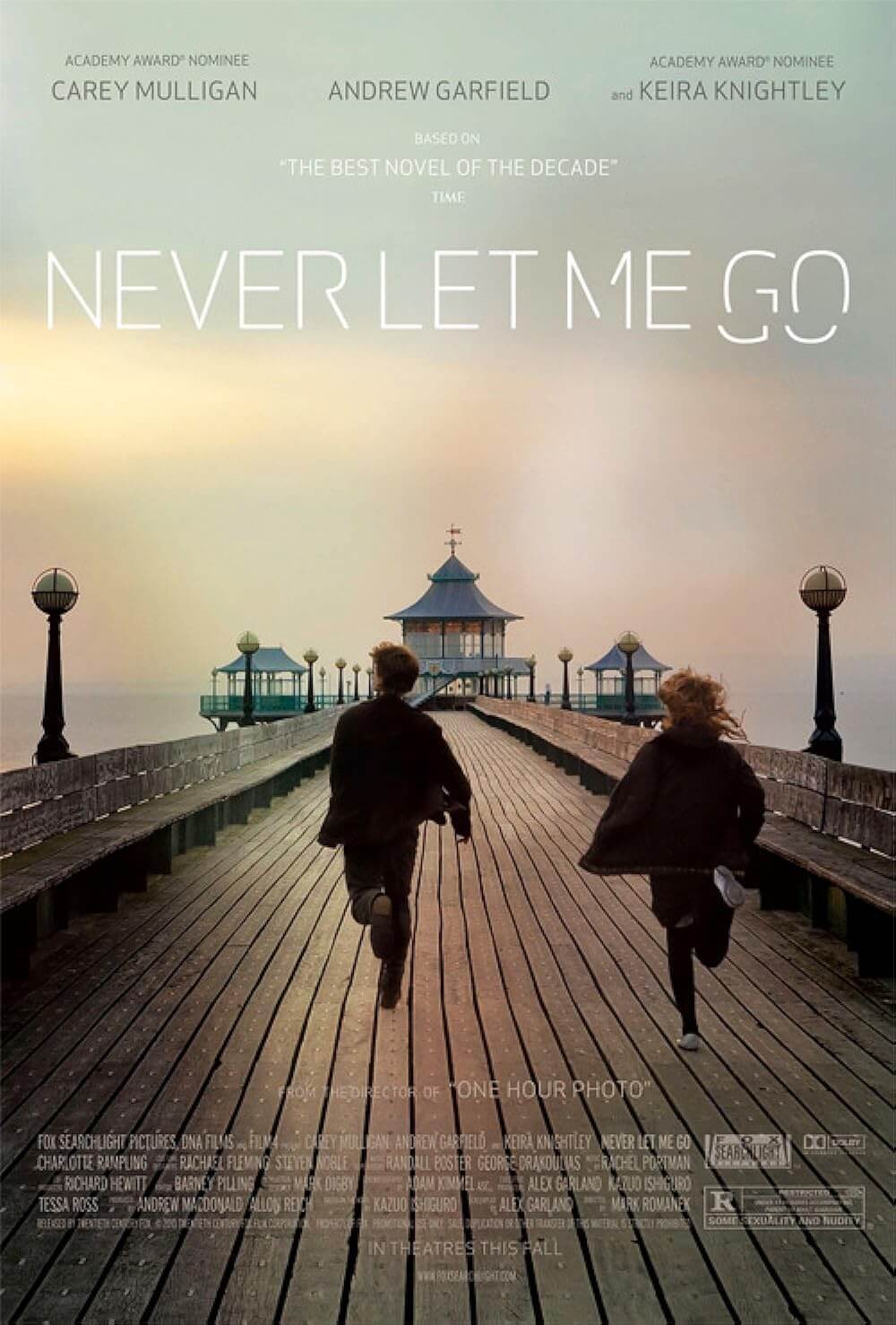

In Never Let Me Go, an adaptation of Kazuo Ishiguro’s bestselling novel from 2005, a medical discovery in 1952 offers a way to extend the human lifespan beyond 100 years. The process, which remains vaguely described within the story, requires organ donations. Accordingly, subsets of children are developed to provide organs; they live brief lives that often end after three decades and a series of four donations, sometimes less. At the boarding school Hailsham in the English countryside, these children grow into a sheltered existence, protected by the school’s caretakers and kept from the outside world to avoid temptations or injury. Yet this frightening science-fiction setup gives way to a carefully paced romance filled with suppressed passions and grave truths, leaving the genre’s often obligatory downfalls by the wayside.

Carey Mulligan plays Kathy, a Carer that, with deep compassion, watches over donors through their operations until they “complete”. She too is a donor and reflects upon her youth in Hailsham, where she grew up alongside friends Tommy (Andrew Garfield) and Ruth (Keira Knightley). Their headmistress Miss Emily (Charlotte Rampling) watches with cold concern over her flock, whereas instructor Miss Lucy (Sally Hawkins) is appalled by the extent of her students’ brainwashing. As students, they hear rumors that two donors in love might have their time extended, to allow the lovers a few more years together. Though Ruth knows Kathy loves Tommy, she claims the boy for herself. And as the years pass, this love triangle becomes more complicated with exposure to the outside world, the discovery of sex, and eventually the confrontation with their ultimate fates.

Of course, it would be easy to gripe that these characters too easily accept their destinies as mere parts for the carving, or that the unprotested absolutism of the film’s medical institution is unrealistically inhuman. Much of the story’s shocking tone results from the unusual way in which this is all perceived as normal. But medical atrocities never occur suddenly; they develop with “progress” and slowly become a regularity. It’s with that developing pace that Ishiguro’s tale unfolds, giving the audience mere pieces until finally, in the last scenes, we gather not only the physical damage this process causes, but the full extent of the emotional devastation as well.

The trio of lead actors gives sublime performances, fully revealing the painful suppression and deliberate naïveté of their intricate roles. Mulligan is sure to earn herself another Oscar nomination, as she’s gradually becoming one of today’s best new actresses. Her ability to articulate Kathy’s pained yet controlled feelings behind such restrained expressions makes her performance one of the most complicated of the year. Knightley, too, captures Ruth’s conniving yet desperate position in a performance that challenges her best roles from Atonement and Pride & Prejudice. And Garfield shows he’s a much more talented actor than his upcoming take on Peter Parker in Sony’s Spider-Man reboot is likely to allow.

Versions of the same type of story have been told before through more typically exciting methods. The cornball 1976 sci-fi yarn Logan’s Run featured youths who break free of their overpopulated dystopia’s ascribed thirty-year euthanasia date. The 1979 horror movie Clonus featured an isolated community in the desert bred for parts to supply the super-rich (and was good enough to deserve the Mystery Science Theater 3000 treatment in 1997). More recently in 2005, Michael Bay’s The Island had detainees escaping their prison with actionized results, only to discover that they were clones bred to provide backup organs for a real-life counterpart.

But director Mark Romanek (One Hour Photo) delivers something more melancholy and thoughtful with Never Let Me Go. Its ruminative purpose and the delicate sci-fi setup emerge only through implication, as opposed to melodramatic expression. Without the need for elaborate special effects or chase sequences, this sci-fi tale, set from the 1960s to the 1990s, has more in common with a Merchant-Ivory production—something like Howards End, filled with grand emotions hiding behind temperate characters and staid manners. To be sure, the story, adapted by Sunshine scribe Alex Garland, avoids becoming an Orwellian allegory wrought by a social message. Instead, this disturbing narrative about believable characters in their fatalistic world offers an affecting drama that stays with the viewer long after the film has ended.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review