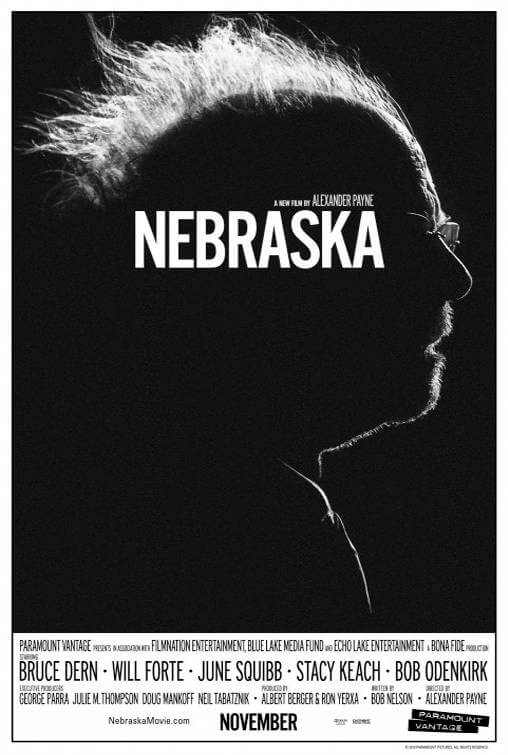

Nebraska

By Brian Eggert |

With Nebraska, Alexander Payne balances on the thin line between honest representation and mordant satire in his depiction of octogenarians and the ideologies of America’s heartland. Director of Election and Sideways, Payne often walks this line, and while admiring the flaws of a people or a region, he also gives them dramatic stakes which emphasize their quirks and yet make them the butt of the joke. Payne has been criticized for poking fun at his subjects, but also praised for the emotional poignancy of his dramatic comedies. With this in mind, Nebraska contains a strong respect for the past and, much like Payne’s About Schmidt and The Descendants, concerns a fading generation that looks back on life and the younger generation’s assessment of this process as it relates to their future. However thoughtful its existential investigation may be, Payne’s film also delivers plenty of quiet laughs at the expense of its characters.

Though the film takes place in a contemporary setting, it opens with a black-and-white Paramount Pictures logo from the 1950s. Along with Phedon Papamichael’s elegant monochrome cinematography, Nebraska’s logo may initially suggest that the film admires the past, but this is a clever deception. Not everything that’s older is simpler, we learn, as we’re introduced to Woody Grant (Bruce Dern, terrific), a weathered, cantankerous, senile old drunk we first meet walking on a highway in his town of Billings, Montana. He’s convinced that he’s the winner of a million-dollar sweepstakes scam. Overlooking that the promotion requires his number to be drawn to win, he makes way to Lincoln, Nebraska, to claim his assumed prize. Woody’s youngest son David (Will Forte) gets the call when the police pick Woody up on the side of the road; without a license, Woody is determined to walk the 800-some miles to Lincoln.

To mollify his father who probably doesn’t have much time left, David agrees to drive Woody to Lincoln to claim his prize. “What’s the harm in indulging his fantasy a little longer,” he argues. After all, it’s something to live for, and David wants the time to better understand his father. Despite the protests of his brother Ross (Bob Odenkirk) and mother Kate (June Squibb), David and Woody head out on a road trip, complete with ponderous shots of the empty road and flat landscape, and a few nostalgic stops along the way. Bob Nelson’s original screenplay interrupts these long, dialogue-less sequences with wry, punctuated humor. Soon they arrive in Woody’s all but vacant hometown of Hawthorne for an impromptu family reunion with his brothers at the home of Ray (Rance Howard) and family. All of them—along with Ray’s two fat sons (Tim Driscoll, Devin Ratray), one of them convicted of sexual assault, both of them dimwits—sit around and watch TV, barely saying a word to each other, speaking up only to comment on cars or how long it takes to drive somewhere.

Before long, it gets out that Woody is a prizewinner, but no one will believe David when he tries to explain that Woody hasn’t won anything. Vultures circle both in and out of the family, the worst of them Woody’s old friend Ed Pegram (Stacy Keach), who believes he’s entitled to a cut of Woody’s loot. When Ross and Kate join the party later on, the no-nonsense Kate puts them in their place—this when she’s not ruminating in uncensored fashion about how old so-and-so wanted into her knickers. Squibb is excellent as a sharp-tongued truth-teller in the vein of Betty White, or maybe Meryl Streep’s Violet Weston in August: Osage County. But with Kate and the other elderlies, there’s a risk of exasperation when watching Nebraska. It’s two hours of half-heard conversations and endless bickering, with nary a moment understood between Woody and David, and all on the pretense that an old man has never before heard of a Publisher’s Clearing House-brand sweepstakes scam. David, meanwhile, is our sad-sack entry point, often a tolerant and quiet observer pf his father’s behavior.

David sighs at his father’s behavior with equal measures of woeful slumps and familial understanding, his tolerance limitless but occasionally facetious in how he talks to Woody like a toddler. Woody’s moments of solemnity and vacancy come and go, but it’s difficult to tell either way. When Woody visits the graveyard or the dilapidated shell of his childhood home, he looks over his past with an inscrutable ponderousness; either his fading mind has allowed him to forget his past, or he chooses not to remember. Dern’s performance, the centerpiece of Nebraska, understates the character’s senility and never portrays his age as a comic caricature. We’re never quite sure if Woody is having an episode of dementia or if he’s back to his unreadable self. However, the film’s bemused quality prevents Woody’s state from slipping into the heartbreak that could have resulted. Payne considers age alongside themes of fading memories and better times, treating the characters the way David cares for his father, with sentiment and dry sardonic humor. Nebraska remains artfully made and incredibly well acted, but his treatment of the characters weakens the drama even as it enhances their humanity.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review