Reader's Choice

Near Dark

By Brian Eggert |

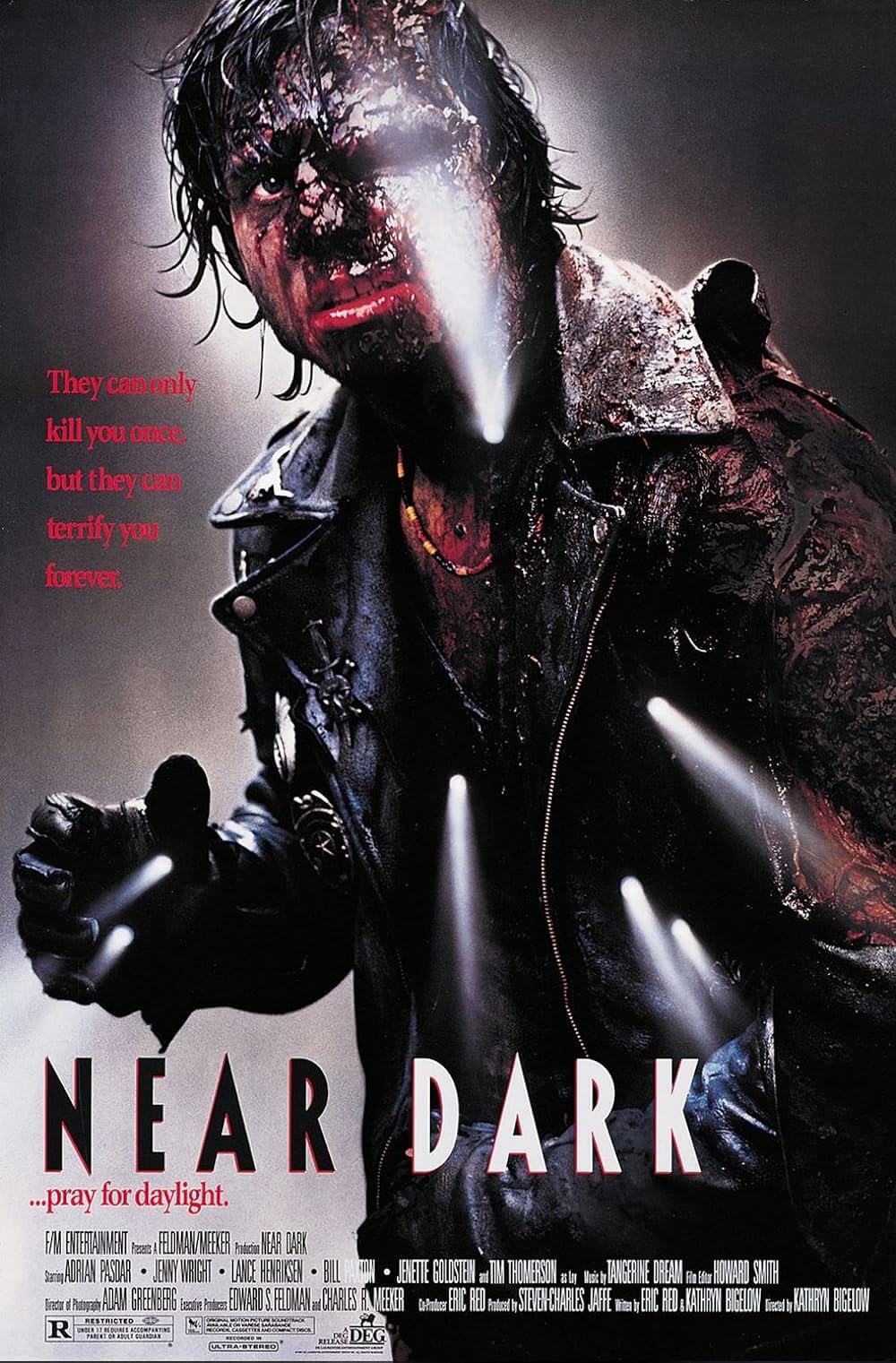

Kathryn Bigelow’s Academy Award for Best Director for The Hurt Locker in 2009 made her the most high-profile female director on the planet. Her work on that film, followed by Zero Dark Thirty (2012) and Detroit (2015), has established her directorial signature with explosive filmmaking. Her name has become synonymous with action and intensity, whereas her choice of subject matter has propelled her into the docubuster realm, in which real-world situations become the substance of her engaging cinema. However her aesthetic has evolved—or devolved, depending on your point of view—since she became the first woman to win an Oscar for Best Director, Bigelow’s earlier work proves more obscure and demanding. With films like the underseen The Loveless (1981) and underrated Strange Days (1995), she bent genres in unexpected ways, rethinking how audiences understood the biker film or the science-fiction film respectively. Her early career concerns of almost poetic violence, genre hybridization, and personal vision were never clearer than with Near Dark from 1987, a vampire yarn marked by gleeful bloodlust, mythological interpretations of the West, and inescapable questions about the film’s attitude toward conventional lifestyles.

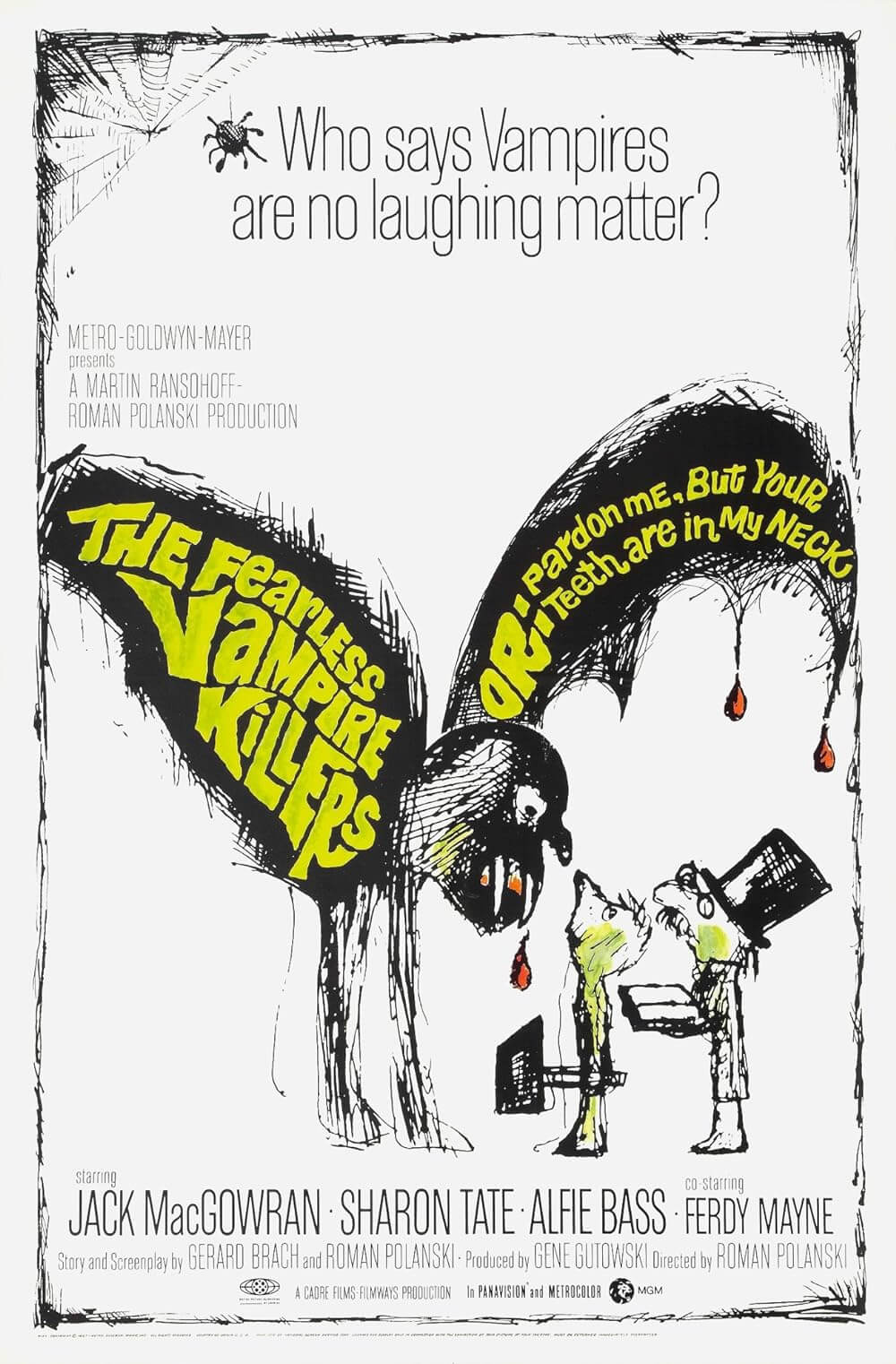

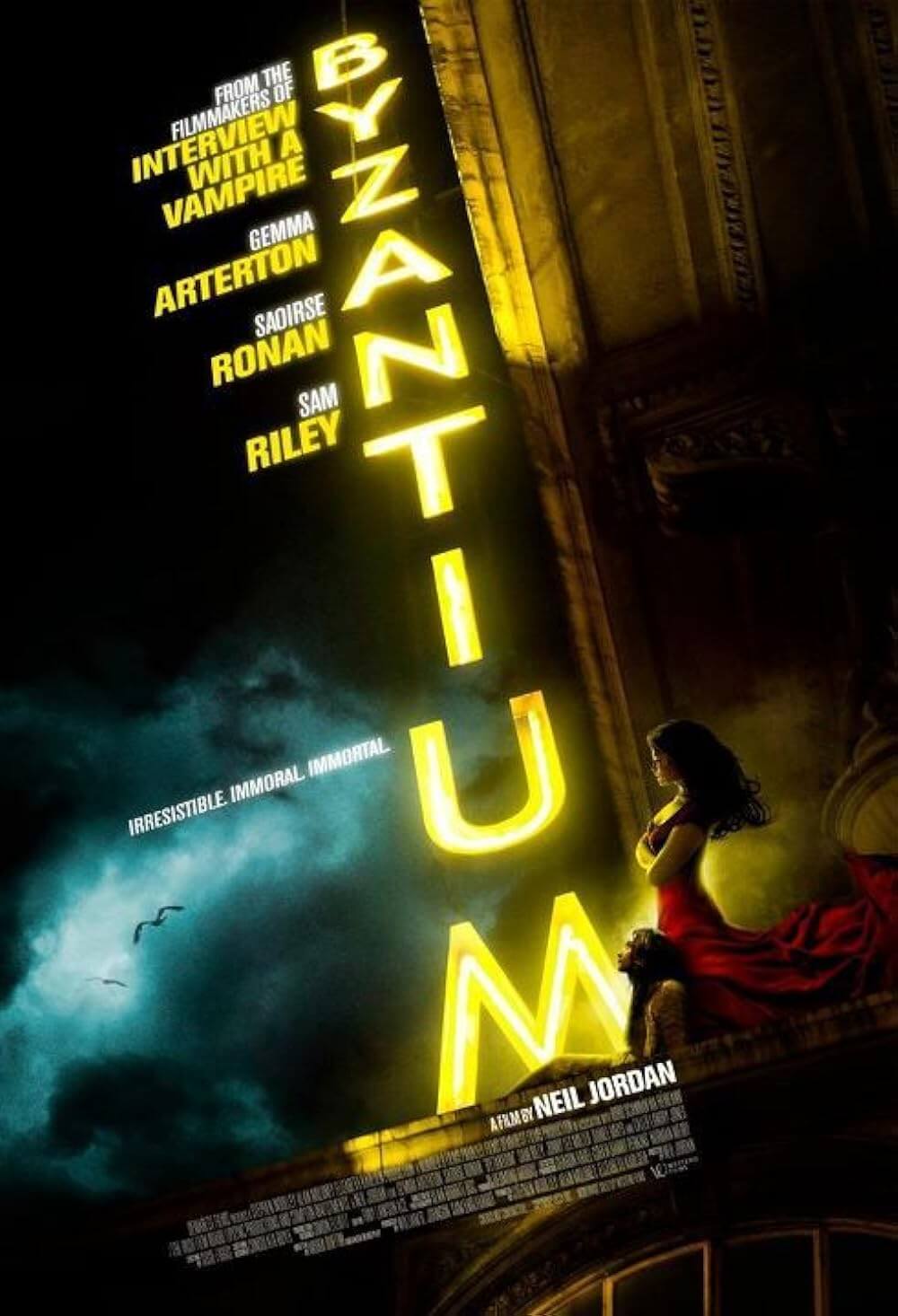

The screenplay by Bigelow and Eric Red both deconstructs the vampire genre and blends it with classical Western motifs. Set in a backwater town of shitkicker bars and pastoral farms, the film occupies a rugged terrain where, not that long ago, pioneers and cowboys invaded, wiped out the indigenous population, and created their own romantic narrative about their settlement. The individualism of Manifest Destiny has replaced the usual Gothic trappings of the vampire genre in Near Dark. It sets aside the period surroundings and decidedly European flair of both Bram Stoker’s original Dracula novel and the litany of subsequent films rooted in that source—both direct adaptations such as the 1931 Bela Lugosi classic and countless others inspired by its legacy. Hammer Film Productions alone produced more than a dozen pictures using the Dracula character, the Hungarian killer Countess Elizabeth Bathory who was thought to be a vampire, or the Gothic setting of Stoker’s book to explore vampires. A revisionist movement away from the vampire’s Gothic origins came in the 1960s, when vampires first appeared in science-fiction like The Last Man on Earth (1964), based on Richard Matheson’s book I Am Legend, as well as Planet of the Vampires (1965). But true revision came with George A. Romero’s Martin (1978), about a fangless young man who may be a vampire or just mentally disturbed, acknowledging that literary monsters are little more than reflections of our inner desires, fears, and impulses.

Near Dark would become one of the first major vampire films to set aside not only the period costumes and historical allusions usually associated with the genre, but also some of the monster characteristics. Other films in the 1980s, such as Fright Night (1985) and The Lost Boys (1987), eschewed the Gothic temperament, but their vampires remained bat-like creatures: they sleep in coffins or hang from the ceiling, avoid mirrors, have fangs that appear at will, and have an aversion to holy water and crucifixes. Bigelow’s film never mentions the word “vampire,” and its monsters, a makeshift family of nomadic killers, have no fangs; they have only a bloodlust, some impressive fingernails, and immortality (“Remember that fire we started in Chicago?” one of them says, in the script’s clumsiest moment). As author Leo Braudy observed, Near Dark’s vampires recall the warped families from Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974) or Wes Craven’s Hooper homage The Hills Have Eyes (1977), except their bond proves far more endearing. There’s a parental quality between their leader, Jesse (Lance Henriksen), and his long-time lover Diamondback (Janette Goldstein). Their two surrogate sons, the raucous and destructive Severen (Bill Paxton) and the eternally adolescent Homer (Joshua John Miller), prove more aggressive than their daughter, Mae (Jenny Wright), a comparatively gentle predator. The family lives and hunts together, driving around backroads in a motorhome with blacked-out windows, searching for victims. They’re far from the Gothic upper-class of Dracula, and their presence in the West demystifies its conquered state.

The film opens with a pointed image: a mosquito drinks from the flesh of Caleb (Adrian Pasdar), a young cowboy adrift in his small Western town. On a night out with his friends, he spots Mae down the street, licking an ice cream cone. Bigelow and Red’s screenplay sets the melancholy yet symbolic mood when Caleb asks her for a bite of her treat. “Bite,” she says reflectively. “I’m dying for a cone,” he adds. She responds hazily, “Dying?” Her first two words in the film, “bite” and “dying” instill an ominous foreshadowing of things to come. Before long, Mae has agreed to a night drive with Caleb, and his pushy demands for a kiss will lead to a vampire bite. In Near Dark, it’s a transformation that begins before dawn, like a disease with an incubation period of minutes. Caleb walks home through a field only to begin smoking as the sunrise hits his flesh. No wonder Mae feels so entranced by the night sky: “It’s dark. It also blinds you,” she says in her dreamy way. But Mae’s family, who pulls Caleb into their motorhome just feet away from his human family, has no need of new members. Jesse gives Caleb a week to prove himself capable of hunting and feeding. If the frightened and sickly newcomer can pull it off, Mae promises him everlasting life.

The film opens with a pointed image: a mosquito drinks from the flesh of Caleb (Adrian Pasdar), a young cowboy adrift in his small Western town. On a night out with his friends, he spots Mae down the street, licking an ice cream cone. Bigelow and Red’s screenplay sets the melancholy yet symbolic mood when Caleb asks her for a bite of her treat. “Bite,” she says reflectively. “I’m dying for a cone,” he adds. She responds hazily, “Dying?” Her first two words in the film, “bite” and “dying” instill an ominous foreshadowing of things to come. Before long, Mae has agreed to a night drive with Caleb, and his pushy demands for a kiss will lead to a vampire bite. In Near Dark, it’s a transformation that begins before dawn, like a disease with an incubation period of minutes. Caleb walks home through a field only to begin smoking as the sunrise hits his flesh. No wonder Mae feels so entranced by the night sky: “It’s dark. It also blinds you,” she says in her dreamy way. But Mae’s family, who pulls Caleb into their motorhome just feet away from his human family, has no need of new members. Jesse gives Caleb a week to prove himself capable of hunting and feeding. If the frightened and sickly newcomer can pull it off, Mae promises him everlasting life.

Near Dark does not look or feel like any vampire film before it. The closest visual comparison might be Joel and Ethan Coen’s debut, Blood Simple (1985), where spare landscapes and a modern cowboy aesthetic combine into a neo-noir. The director of photography, Adam Greenberg, who shot The Terminator (1984) and Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991) for Bigelow’s ex-husband James Cameron, evokes Robby Müller’s work on Paris, Texas (1984) at times with his use of glowing neon lights. The empty streets at night, freshly hosed down by the crew and illuminated by street lights, make Caleb and his new vampire family feel like the only people on Earth. Alternatively, Greenberg shoots scenes during the day that are saturated in dust, creating beams of sunlight that leave us hyper-aware of its substance and thus the danger it represents to the vampire family. This is imagery used both on the film’s theatrical poster and again in a scene where authorities corner the family in a motel room and open fire, creating dozens of holes through which sunlight burns more than the bullets do. It’s worth noting that Greenberg isn’t the only Cameron connection; Henriksen, Paxton, and Goldstein all appeared as hardened Colonial Marines in the director’s sequel Aliens (1986)—whose title winkingly appears on a movie theater marquee in the background of Near Dark.

Bigelow shows no restraint in her use of visual and thematic symbolism, but her choices have been applied with such a sure hand that the otherwise obvious imagery feels inspired. Take a scene where Caleb, who refuses to kill for a meal, drinks from the incision Mae opens on her wrist. Bigelow frames the feeding against an oil pump, evoking an association between the machine and a human heart pumping blood as Caleb greedily drinks. In other scenes, Bigelow and Red’s script makes several allusions to vampirism as a kind of drug addiction. When a frightened Caleb tries to escape the vampires and return to his original family—a motherless unit with a veterinarian father (Tim Thomerson) and a young sister (Marcie Leeds)—he staggers, starving and sweaty, dusted in ash from his encounter with the Sun, into a bus station. Caleb’s refusal to kill leaves him shivering with what appear to be withdrawal symptoms. Both the bus station clerk and a local cop assume he’s on drugs. “What’re you on?” he’s asked. Caleb eventually encounters his family again, telling them “I’m sick,” not that he’s a vampire. They treat him like an addict in need of detoxification, which comes in the form of a blood transfusion by his father—possibly the only reference to the failed transfusions in Bram Stoker’s novel. Horror films in the 1980s, at the height of the so-called War on Drugs, often used their monstrosities as a metaphor for drug addiction (see also Brain Damage from 1988).

If Bigelow holds onto any aspect of the Gothic vampire from Stoker’s original book, it’s the promise of eternal life that Dracula gives Mina, which Mae hopes to give Caleb. In both the book and Near Dark, there’s an underlying allure of escape from the doldrums of conventional life into something strange and usual, the promise of an alternative to normality by acquiring life everlasting. In the first scenes, Caleb appears bored in Small Town, America, and his family’s humdrum farm life hardly promises an exciting future. Mae, carefully framed in an S-curve with her ice cream cone to attract prey, embodies the limitless possibility of Caleb’s future. In the end, after transfusions save both Caleb and Mae (from what Stoker called “the curse of immortality” in which they would spend “age after age adding new victims and multiplying the evils of the world”), Caleb gets the best of both worlds: an alternative life alongside Mae, albeit free from the murderous necessity of vampirism. Elsewhere, the curse is tragically articulated through Homer, an ancient vampire trapped in a boy’s body. Homer, who uses his youthful appearance to ensnare his victims in a nasty trick involving a faux bike accident, hopes to turn Caleb’s young sister into a companion. Still, his appearance makes him oddly sympathetic when he cries like a child in fear of daylight and takes comfort in the arms of Diamondback.

If Bigelow holds onto any aspect of the Gothic vampire from Stoker’s original book, it’s the promise of eternal life that Dracula gives Mina, which Mae hopes to give Caleb. In both the book and Near Dark, there’s an underlying allure of escape from the doldrums of conventional life into something strange and usual, the promise of an alternative to normality by acquiring life everlasting. In the first scenes, Caleb appears bored in Small Town, America, and his family’s humdrum farm life hardly promises an exciting future. Mae, carefully framed in an S-curve with her ice cream cone to attract prey, embodies the limitless possibility of Caleb’s future. In the end, after transfusions save both Caleb and Mae (from what Stoker called “the curse of immortality” in which they would spend “age after age adding new victims and multiplying the evils of the world”), Caleb gets the best of both worlds: an alternative life alongside Mae, albeit free from the murderous necessity of vampirism. Elsewhere, the curse is tragically articulated through Homer, an ancient vampire trapped in a boy’s body. Homer, who uses his youthful appearance to ensnare his victims in a nasty trick involving a faux bike accident, hopes to turn Caleb’s young sister into a companion. Still, his appearance makes him oddly sympathetic when he cries like a child in fear of daylight and takes comfort in the arms of Diamondback.

Whatever sympathy Bigelow establishes for the vampire family in the first half of Near Dark comes crashing down later, when they proceed to taunt and slay the guests and staff at a local dive bar. They hope to force Caleb into killing his first victim by provoking a confrontation. It’s the film’s best sequence, as it shows how the family, Severen above all (Paxton is wonderfully unhinged here), delight in torturing and frightening their victims—in effect playing with their food with what critic Anna Powell called “orgiastic” pleasure, with “blood spurting orgasmically as the vampires get their kicks.” In the deeply unsettling scene, they fill a beer glass with blood drawn from a waitress, Severen crushes a biker’s head in his hands, and he slices the bartender’s neck with his spur. Mae reveals her sadistic side, dancing with a young man (James Le Gros) who has just witnessed a slaughter, and holds him for her beau. But Caleb still resists killing the easy prey, and the bar patron escapes—eventually, he alerts the authorities to Jesse’s clan, leading to a string of events that ends with the family’s demise. When Jesse and company have finished at the bar, they burn the place to the ground.

In Western terms, the vampires in Near Dark occupy the role of Indians, which early Westerns by John Ford depicted as savage and untamed. Like cinematic Indians, the vampires raid civilized spaces, burn them down, and leave bodies in their wake. They live nomadic lives, unhinged from standards of law and order instituted by white settlers, attuned to an aspect of Nature that the civilized world does not understand. Mae insists that, now that Caleb is immortal, they can do “anything we want until the end of time,” meaning there’s no sense of finality or limitation to their lives. These vampires travel their Western landscape as wild, subhuman creatures that defy society as defined by European culture. And, just as the Comanches do in Ford’s The Searchers (1956), they kidnap children and attempt to integrate them into their tribe. Caleb’s father and sister, then, occupy the John Wayne role in this Fordian structure, tracking down the savages until they are confronted with the reality that their near-converted family member may be a lost cause. It’s no wonder that Bigelow dressed the vampires not in Gothic attire from the past, but in punk gear, leather and torn jeans, to represent a familiar cultural identity that viewers in the 1980s would associate as a nonconforming type—the vampire punk is just as anti-civilization as the cinematic Indian, emblems of social decay and rebellion in the eyes of a conservative society.

By positioning the vampires as both villainous and alternative to conventional forms of life, Near Dark could be seen as a reaffirmation of civilization, an expression that flirts with rebellion only to restore order to the universe. Caleb, the blandest of heroes as an attractive white male cowboy who remains largely passive for much of the film, dreams of escaping his repressive life on the farm, where work, duty, and family represent social norms. With Mae’s help, he hopes to liberate himself into an anti-establishment lifestyle—an impulse captured visually in the contrast of his life in the sunlight and Mae’s life in the darkness. To be sure, the difference between vampires and humans is the difference between night and day. Caleb and Mae appeal to each other most as these two poles transition at dusk and dawn—the moments in the film when the lovers seem most dependent on one another. Caleb ultimately rejects the nontraditional lifestyle of vampirism and, with Mae by his side, is reassimilated into conventional society. “I’ve brought you home,” Caleb tells her reassuringly in the end, the idea of home signaling their future domesticity. “I’m afraid,” Mae says, looking at the sunrise for the first time in a long time. “Don’t be,” says Caleb, “it’s just the Sun.” This finale has led some scholars to accuse Near Dark of a neoconservative worldview.

By positioning the vampires as both villainous and alternative to conventional forms of life, Near Dark could be seen as a reaffirmation of civilization, an expression that flirts with rebellion only to restore order to the universe. Caleb, the blandest of heroes as an attractive white male cowboy who remains largely passive for much of the film, dreams of escaping his repressive life on the farm, where work, duty, and family represent social norms. With Mae’s help, he hopes to liberate himself into an anti-establishment lifestyle—an impulse captured visually in the contrast of his life in the sunlight and Mae’s life in the darkness. To be sure, the difference between vampires and humans is the difference between night and day. Caleb and Mae appeal to each other most as these two poles transition at dusk and dawn—the moments in the film when the lovers seem most dependent on one another. Caleb ultimately rejects the nontraditional lifestyle of vampirism and, with Mae by his side, is reassimilated into conventional society. “I’ve brought you home,” Caleb tells her reassuringly in the end, the idea of home signaling their future domesticity. “I’m afraid,” Mae says, looking at the sunrise for the first time in a long time. “Don’t be,” says Caleb, “it’s just the Sun.” This finale has led some scholars to accuse Near Dark of a neoconservative worldview.

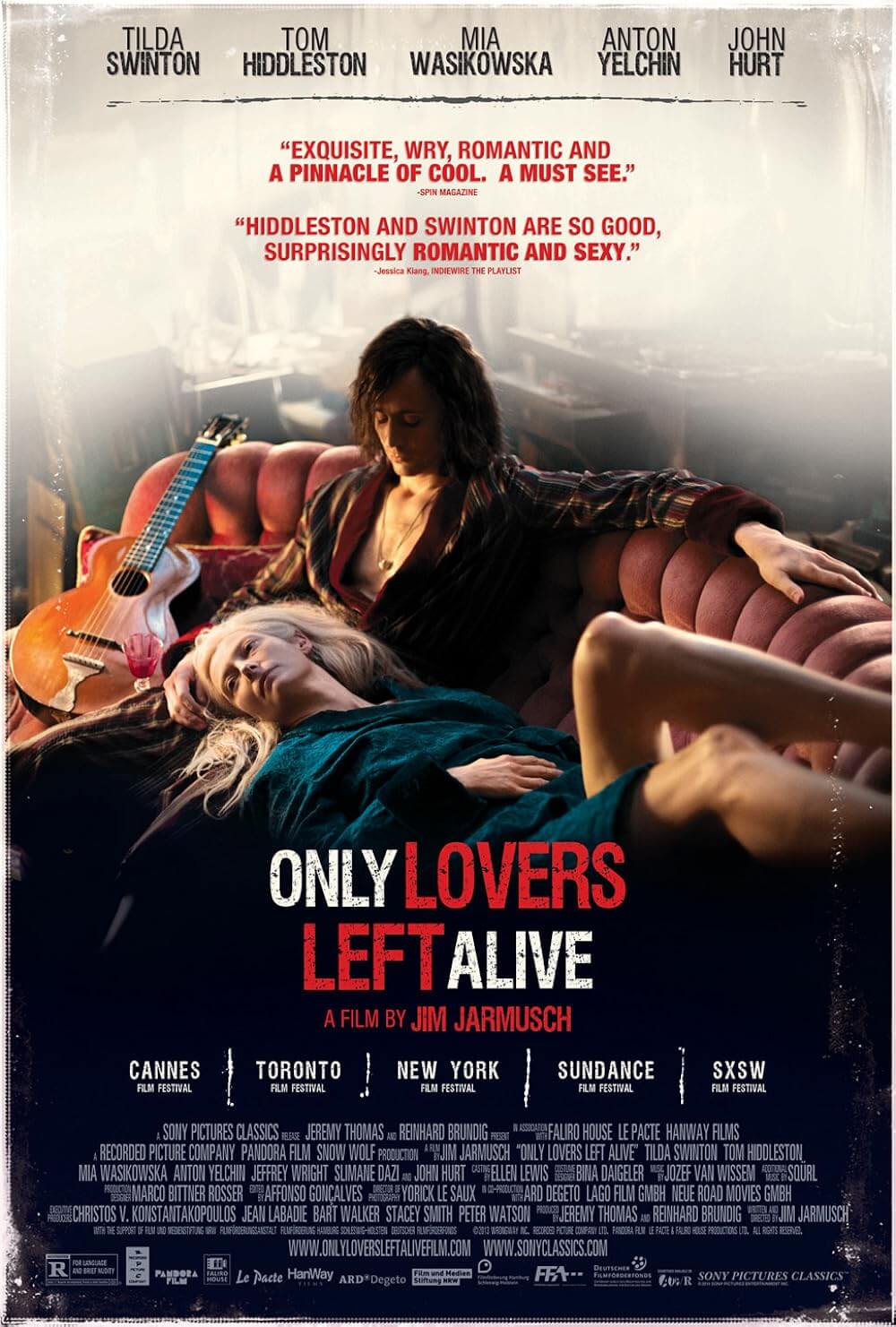

Alternatively, consider how appealing Bigelow has made Jesse’s family, and how Near Dark spends more time with the alluring unconventional lifestyle than Caleb’s civilized one as a farmhand. Their freedom to act on every violent impulse, and the power inherent to that freedom, becomes evident when Caleb strikes a patron in the bar scene, sending him across the bar and against a wall. There’s a brief shot of Caleb both bemused and enchanted by his new abilities. Between Caleb’s strength, the promise of immortality, and his romantic association with a creature of the night, Mae, the film makes vampirism look attractive. With this, Bigelow raises questions in the viewer about where our loyalties belong, even as the film’s trajectory affirms conservative views about ideological norms. By contrast, consider how later vampire romances such as author Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight franchise embraced a progressive lifestyle, dreaming up a fantasy in which humans and the toned-down vampires (who do not prey on humans and sparkle in the sunlight) could meet somewhere between two extremes, living happily ever after. If Near Dark ultimately conforms to traditional lifestyles, it also raises questions about and presents alternatives to the established order of things.

Near Dark’s push-and-pull between the light and dark continues to resonate. These symbols represent Bigelow’s postmodern use of genres, her questions about conventional and alternative cultures, and her distinct voice as an auteur. At every turn, the film offers nontraditional options, preferring instead to operate in the nuanced spaces between daylight and sunlight. As a result, neither extreme feels entirely comfortable or unproblematic in the film. Still, it’s a richly interpretable and thoughtful genre exercise, realized with a form of distinct 1980s touches: Tangerine Dream’s playful score; wild performances by Henriksen and Paxton; and scenes of intense, sometimes over-the-top violence—such as Caleb driving a truck into Severen, who survives only to become a walking showpiece of gore makeup. It’s entirely enjoyable as an escapist vampire lark, but it continues to reveal itself, unlike, say, The Lost Boys released the same year. Underneath its familiar and unfamiliar surfaces, Near Dark considers the dynamics between two worlds, and that ambiguity has continued to draw audiences into its edgy, unpolished spell.

(Editor’s Note: This review was suggested and commissioned on Patreon by Ann. Thanks for your continued support!)

Bibliography:

Braudy, Leo. “Near Dark: An Appreciation.” Film Quarterly, vol. 64, no. 2, 2010, pp. 29–32. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/fq.2010.64.2.29. Accessed 11 Apr. 2020.

Jones, Sarah Gwenllian. “Vampires, Indians and the Queer Fantastic: Kathryn Bigelow’s Near Dark.” The Cinema of Kathryn Bigelow: Hollywood Transgressor, edited by Deborah Jermyn, Sean Redmond. Wallflower Press, 2003, pp. 58-71.

Powell, Anna. “Blood on the Borders: Near Dark and Blue Steel,” Screen, 35, 2 (summer), 1994, pp. 136-156.

Schneider, Steven Jay. “‘Suck… don’t suck. Framing ideology in Kathryn Bigelow’s Near Dark.” The Cinema of Kathryn Bigelow: Hollywood Transgressor, edited by Deborah Jermyn, Sean Redmond. Wallflower Press, 2003, pp. 72-90.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review