Napoleon

By Brian Eggert |

A decisive moment in Ridley Scott’s Napoleon finds the French Emperor, played by Joaquin Phoenix, examining an Egyptian sarcophagus and the pharaoh inside. Bonaparte approaches the mummy, who stands taller than he does, so he uses a stool to meet the preserved ruler eye-to-eye—or, in the mummy’s case, eye holes. The scene gives a telling assessment of a man desperate to make his mark on history, to leave a legacy worthy of a god-king’s pyramid. Napoleon aspired to become one of the great leaders from antiquity, such as Julius Caesar or Alexander the Great—inspired by his fervent study of Plutarch’s Parallel Lives, a book about prominent figures from Greek and Roman history. And at his height, Napoleon conquered much of Europe. But his rule was neither noble nor admirable in Scott’s film. “He can’t help himself,” observes one opponent, who cannily sizes up Napoleon’s fragile ego. Rather, the film portrays a despot with an inferiority complex, one of history’s most iconic figures brought to life by Scott and Phoenix. A classical production where historical inaccuracies run rampant, the cast speaks in primarily British accents, and the production spared no expense, Napoleon is a true Hollywood epic. The film falls into the category of they don’t make ’em like they used to filmmaking. But few other directors working today could have told this story with the depth and scope that Scott achieves, and the result is an inspired marriage between director, actor, and subject matter.

Originally titled Kitbag—after a famous quote attributed to Bonaparte about French soldiers who, primed for promotion, always carry a Marshal’s baton with them—the screenplay by David Scarpa serves its subject far better than the writer’s last collaboration with Scott, 2017’s All the Money in the World. Of course, this isn’t the first film about Bonaparte. The subject matter has been confronted by ambitious filmmakers, such as French director Abel Gance’s five-and-a-half-hour silent epic Napoléon (1927) or Russian filmmaker Sergei Bondarchuk’s long-absent Waterloo (1970). Stanley Kubrick famously wanted to make a film about Bonaparte, but the vastness of the topic consumed him, and he settled on Barry Lyndon (1975), set just a few decades before Bonaparte’s rise to power, instead. Steven Spielberg is reportedly developing Kubrick’s unfinished biopic into a limited series for Max (née HBO Max, née HBO). Scott’s picture required a massive $200 million investment from Apple Studios, an amount equal to what they paid for Martin Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon. If writing huge checks so masterful octogenarian directors can make ambitious projects doesn’t exactly prove profitable, it at least shows the company has good taste.

The film opens in 1793 during the French Revolution, with the Queen, Marie-Antoinette (Catherine Walker), facing the so-called Reign of Terror’s bloodthirsty mob and then the guillotine. Bonaparte, then a gunnery sergeant, watches her beheading broodingly. He knows the fall of one regime means the rise of another. Sure enough, he’s soon promoted by Paul Barras (Tahar Rahim), a member of the Directory, a five-man political committee that led France after the Revolution. Then, ever the opportunist who’s desperate for attention and to prove himself, Bonaparte nervously leads a major attack on a seaside port. Though he’s wobbly and hesitant at first, he’s also a shrewd tactician whose plan proves a success, leading to more promotions—his brother, Lucien (Matthew Needham), a close advisor, always by his side. His eventual liberation of the French people by the Terror’s end sees over 41,000 prisoners released, among them Joséphine (Vanessa Kirby, excellent), whom Bonaparte first meets at a Survivor’s Ball—before a grotesque play about Marie-Antoinette getting her head back only so she can fellate demons in hell.

The film opens in 1793 during the French Revolution, with the Queen, Marie-Antoinette (Catherine Walker), facing the so-called Reign of Terror’s bloodthirsty mob and then the guillotine. Bonaparte, then a gunnery sergeant, watches her beheading broodingly. He knows the fall of one regime means the rise of another. Sure enough, he’s soon promoted by Paul Barras (Tahar Rahim), a member of the Directory, a five-man political committee that led France after the Revolution. Then, ever the opportunist who’s desperate for attention and to prove himself, Bonaparte nervously leads a major attack on a seaside port. Though he’s wobbly and hesitant at first, he’s also a shrewd tactician whose plan proves a success, leading to more promotions—his brother, Lucien (Matthew Needham), a close advisor, always by his side. His eventual liberation of the French people by the Terror’s end sees over 41,000 prisoners released, among them Joséphine (Vanessa Kirby, excellent), whom Bonaparte first meets at a Survivor’s Ball—before a grotesque play about Marie-Antoinette getting her head back only so she can fellate demons in hell.

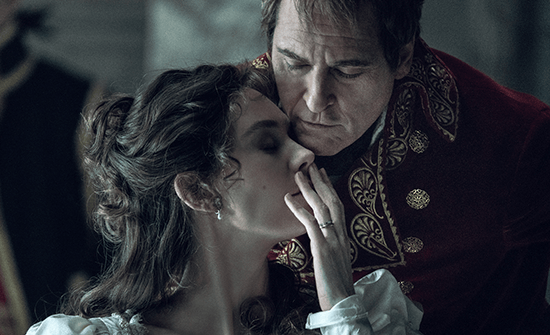

They’re married by the time he’s running the French army and enter into a borderline dom-sub relationship that alternates roles, depending on the scene. For instance, he almost melts with desire when she gives him one look between her spread legs. But then, he approaches his conquest of French dissenters with the same jackhammer ferocity he applies to Joséphine in the bedroom. Over their 15-year marriage, the relationship is driven by his desperate need to control Joséphine. Scarpa’s script suggests that his failure to dominate this intrepid woman led to his desperate need to conquer the world. Their dynamic is less portrayed as one of history’s great love affairs but as two people grappling for power within their worlds. In one scene, he demands that she say he’s the “most important thing in the world,” but later, the tables turn, and she forces him to admit, “I am nothing without you.” If Phoenix isn’t quite as diminutive looking as Napoleon is usually depicted, his characterization reveals him as a small man. When, over a meal in Egypt, one of his subordinates shares the news that Joséphine has taken a lover, Bonaparte scrambles to reassert himself in the situation: “No dessert for you,” he tells the messenger, as though denying the man sweets will somehow make her infidelity right.

Phoenix played an insatiable tyrant for Scott once before in Gladiator (2000), but there’s far more to his performance as Bonaparte. Somewhere between Donald Trump and his Oscar-winning take on The Joker, his Napoleon is pathetic and monstrous, often to buffoonish effect. It’s a performance that’s both comedic and pathological, and cleverly realized without being too showy. Phoenix captures how Bonaparte’s insecurities manifest when he nervously straightens his hat or trips over his feet and lashes out when insulted. At one point, he screams at a British politician, “You think you’re so great because you have boats!” like a spiteful teen. To be sure, other world leaders call out his “lack of good manners” and observe that he should have never been allowed to continue this long. Elsewhere, he has an almost narcoleptic disinterest in anything not involving him. And those who defy him are met with scorn and violence. When he’s powerless to convince the disapproving Directory that he should take over as Emperor, he scrambles away, dupes some soldiers to follow him, and holds his dissenters at gunpoint to acquire their approval. He’s just as malicious with Joséphine, who cannot bear him a child—a detail uncovered in an insidious plot by his mother (Sinéad Cusack)—so he divorces her and relegates her to Château de Malmaison. Though she’s been dejected, he visits Joséphine and remarks on her gloom: “You look best when you’re happy.” And when he produces an heir with his new wife, he brings the child to Joséphine out of blind pride—after all, when you believe the whole world is yours, it doesn’t occur to you that your ex-wife might not want to meet the child she could not have.

Of course, Napoleon is familiar material for the director whose Napoleonic drama The Duellists (1977) marked his feature debut and one of his best films. Similar to that production, Scott and cinematographer Dariusz Wolski draw some of their color palette and imagery for Napoleon from French paintings of the era by Jacques-Louis David, Jean-Léon Gérôme, and François Bouchot. The romanticized visuals are gorgeous and expansive, lending war sequences a quality that, refreshingly, looks like Scott has used real landscapes instead of digital trickery to achieve such painterly compositions. A few scenes include obvious CGI, such as a shocking moment when a cannonball strikes Napoleon’s horse, leaving him shaken. But most of the effect shots are so good that they blend into the proceedings and rarely distract the viewer, allowing us to concentrate on the immediacy or emotional consequence of the scene. Most impressive is the battle of Austerlitz sequence, set in 1805, when Napoleon is at his strategic best. But inevitably, at Waterloo, his ego gets the best of him. Much of the film is set to a memorable score by Martin Phipps, though Scott also includes anachronistic French rebellion songs from that sound recorded in the early twentieth century. Along with Phoenix’s slyly modern screen presence and defiantly American accent, these songs contain a hint of wry postmodernism.

Of course, Napoleon is familiar material for the director whose Napoleonic drama The Duellists (1977) marked his feature debut and one of his best films. Similar to that production, Scott and cinematographer Dariusz Wolski draw some of their color palette and imagery for Napoleon from French paintings of the era by Jacques-Louis David, Jean-Léon Gérôme, and François Bouchot. The romanticized visuals are gorgeous and expansive, lending war sequences a quality that, refreshingly, looks like Scott has used real landscapes instead of digital trickery to achieve such painterly compositions. A few scenes include obvious CGI, such as a shocking moment when a cannonball strikes Napoleon’s horse, leaving him shaken. But most of the effect shots are so good that they blend into the proceedings and rarely distract the viewer, allowing us to concentrate on the immediacy or emotional consequence of the scene. Most impressive is the battle of Austerlitz sequence, set in 1805, when Napoleon is at his strategic best. But inevitably, at Waterloo, his ego gets the best of him. Much of the film is set to a memorable score by Martin Phipps, though Scott also includes anachronistic French rebellion songs from that sound recorded in the early twentieth century. Along with Phoenix’s slyly modern screen presence and defiantly American accent, these songs contain a hint of wry postmodernism.

Running 157 minutes, Napoleon has been edited to a breezy clip by Claire Simpson and Sam Restivo, alternating between scenes of Napoleon and Joséphine and rousing battle sequences that emerge out of political intrigue. Those familiar enough with French history to recognize the production’s omissions on Bonaparte’s timeline will be pleased to know that Scott has a four-hour director’s cut set to debut on Apple TV+ sometime next year. Several scenes in the theatrical trailer do not appear in the theatrical cut, and one can see where Scott could flesh out the relationship between Napoleon and Joséphine, giving more screentime to Kirby. But expecting scholarly historical accuracy from the production would be ill-advised, as some historians have noted the film is not without error, much to the director’s annoyance. But Scott isn’t in the business of conveying scholarly history on film; he crafts Hollywood epics. (Anyone who watched the movie about a historical subject instead of reading a book surely received a poor grade on their history exam). What remains onscreen is impressive and beautifully orchestrated by Scott, whose experience with epics includes the maligned Exodus: Gods and Kings (2014), his superb director’s cut of Kingdom of Heaven (2005), the underrated Robin Hood (2010), the sharply intelligent The Last Duel (2021), and the contemptible 1492: Conquest of Paradise (1992).

Napoleon is among Scott’s finest epics, and one hopes it may become a masterpiece in the longer iteration. But unlike Kingdom of Heaven, where the theatrical cut was practically nonsensical next to the marvelous extended version, the new film’s theatrical cut warrants immediate praise. It’s a condemning portrait of Napoleon’s desire to liberate the conquered by conquering them in the name of peace and security, making his victory over his enemies “in the best interest of Europe.” Whatever his excuse, his actions serve only his feeble, Trumpian ego. Consider the late scene where Napoleon brags to children that he has a studied knowledge of where to place cannons, yet he somehow failed to impart that information to his military commanders at Waterloo. Terrifically performed by Phoenix, Bonaparte is a fascinating historical figure whose inadequacy and delicate pride, even among children, cost millions of French lives. While the production never looks unconvincing in all its majestic sequences and grand panoramas, the amusingly critical assessment of Napoleon resonates and gives the scopic film dimension.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review