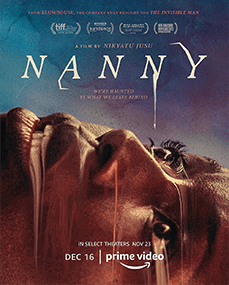

Nanny

By Brian Eggert |

Note: This review was originally published for the 2022 Twin Cities Film Fest on October 27, 2022. The film will be released in theaters on November 23, followed by Amazon Prime Video on December 16.

Nikyatu Jusu’s Nanny uses the trappings of a horror movie to characterize the immigrant experience. Films about immigrants often take the form of starry historical dramas, such as Brooklyn (2015), with its romanticized view of coming to America and falling in love under picturesque circumstances. However, they also deal in gritty realism, vérité-style camerawork, and desperate conditions in films like Dirty Pretty Things (2002) and Most Beautiful Island (2017). In her expressive and confidently composed debut, Jusu uses West African folklore and haunting imagery to conjure feelings of displacement and longing for one’s homeland. But the film does more than convey the psychological state of its protagonist in familiar horror grammar; it also considers the layers of immigrant identity—how the hope for a better future is contrasted by feelings of regret and longing for those left behind. At its core, Jusu’s first feature is a powerful metaphor for the almost supernatural way culture imprints on someone’s identity.

The story centers on Aisha (Anna Diop), a former teacher from Senegal, who’s hired as a nanny by a well-to-do New York couple: Amy (Michelle Monaghan), whose marriage to her journalist husband Adam (Morgan Spector) is uneasy at best. Aisha arrives for her first day on the job and, following previous instructions from Amy, washes her hands before greeting her new employer. Indeed, Amy has an entire three-ring binder with house rules and how-tos, including the dietary restrictions of her daughter, Rose (Rose Decker). But Rose refuses to eat the dull, carefully labeled, and sealed containers of foodstuff that Amy prepares for her; however, she has no problem eating Aisha’s jollof rice, signaling the disconnect between mother and daughter. Over time, it’s apparent that Amy’s neuroses have impacted Rose. Not that Aisha can say anything or make alterations to Amy’s instructions—Amy keeps cameras around the house to monitor Aisha’s progress. What’s more, Aisha needs the money; she’s saving to bring her young son Lamine from Senegal to America.

From this setup, Jusu takes obvious inspiration from Ousmane Sembène’s La noire de… (1966), generally considered to be the first film by a sub-Saharan African director. Both titles follow a young woman from Dakar who lands a job looking after the child of privileged white people. Both show how the white couple takes advantage of her role, resulting in virtual enslavement when the list of chores goes beyond childcare and extends into cooking and cleaning. Both films feature the nanny sometimes occupying a room in her employer’s apartment; in Aisha’s case, Amy expects her to work several unexpected “overnights” for extra pay, which she is late to disburse. Amy even buys Aisha a dress to wear for a cocktail party she’s hosting. And in both, the specter of the nanny’s African roots haunts the protagonist. In Sembène’s film, the figure appears in the form of a mask. But Jusu’s film mines folklore even deeper and shows more interest in the particulars of Aisha’s inner life. In contrast, Sembène used his character’s passivity and remoteness as a form of silent protest and political symbolism.

Although Nanny and La noire de… have much in common, Jusu remains more interested in the particulars of her main character. Focused on reuniting with Lamine, Aisha cannot help but feel troubled by his absence as she cares for Rose. The presence of her former self lingers and materializes in nightmarish hallucinations—the sensation of being submerged in water or stalked by a spider. These visions invade Aisha’s days and interrupt her nights, leaving her with a sense that something is horribly wrong. Her alienation worsens when her calls home to Lamine, who stays with a relative, go unanswered. Her only reprieve is a new romance with Malik (Sinqua Walls), the charming doorman in Amy and Adam’s building. With him, she can express that she feels owned by her employers. And with his grandmother Kathleen (Leslie Uggams), who’s well-versed in African folklore, she learns that her hauntings aren’t necessarily good or evil. Rather, the spidery trickster Anansi and the mermaid-like Mami Wata, along with visions of black mold and drowning, seek to bring Aisha closer to herself—albeit in disturbing ways.

Although Nanny and La noire de… have much in common, Jusu remains more interested in the particulars of her main character. Focused on reuniting with Lamine, Aisha cannot help but feel troubled by his absence as she cares for Rose. The presence of her former self lingers and materializes in nightmarish hallucinations—the sensation of being submerged in water or stalked by a spider. These visions invade Aisha’s days and interrupt her nights, leaving her with a sense that something is horribly wrong. Her alienation worsens when her calls home to Lamine, who stays with a relative, go unanswered. Her only reprieve is a new romance with Malik (Sinqua Walls), the charming doorman in Amy and Adam’s building. With him, she can express that she feels owned by her employers. And with his grandmother Kathleen (Leslie Uggams), who’s well-versed in African folklore, she learns that her hauntings aren’t necessarily good or evil. Rather, the spidery trickster Anansi and the mermaid-like Mami Wata, along with visions of black mold and drowning, seek to bring Aisha closer to herself—albeit in disturbing ways.

Jusu’s control of tone is particularly impressive throughout Nanny, a slow-burning affair marked by some incredible use of light and a transfixing score by musicians Tanerélle (aka Mama Saturn) and composer Bartek Gliniak. The film’s look and feel have a disorienting effect, creating a sense of Aisha’s dislocation in America. Whether it’s a creatively off-kilter angle by cinematographer Rina Yang or the hued illumination in Amy and Adam’s icy, modern, “overpriced shoebox” apartment, there’s a persistent feeling that something is very wrong. The creatures in Aisha’s head, too, are realized with unnerving visuals. Anansi’s presence, marked by spiders crawling into Aisha’s mouth at night or outstretched spider-leg shadows on a bedroom wall, is also a warning. Mami Wata is both fantastical and sublime, rendered with a combination of CGI and practical effects that look convincing. Both spirits, we learn, mean well despite their sometimes frightening methods. As Kathleen explains, “They refuse to be ruled,” so they likely want Aisha to resist her current subjugation as well.

However, for all of Nanny’s unsettling imagery and persistent feelings of dread, the story is somewhat predictable. The arrival of a third-act twist doesn’t come as a surprise; it’s an obvious development, even though Jusu treats the moment as a gotcha for the audience that cheapens the dramatic impact. Still, the director shows an undeniable knack for pacing, mood, and disturbing imagery that makes the viewer lean in toward the screen, ever unsure of what’s real and what’s inside Aisha’s head. Diop’s nuanced performance also lands every emotion, capturing Aisha’s careful negotiation of her status as a spiritually imprisoned outsider who never completely feels at ease in her new home. Diop conveys a strength that makes Aisha’s endurance through the terrifying experiences and sensations under her supernatural guides believable. It’s an excellent performance in a powerful first film that bodes well for what Jusu has in store next.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review