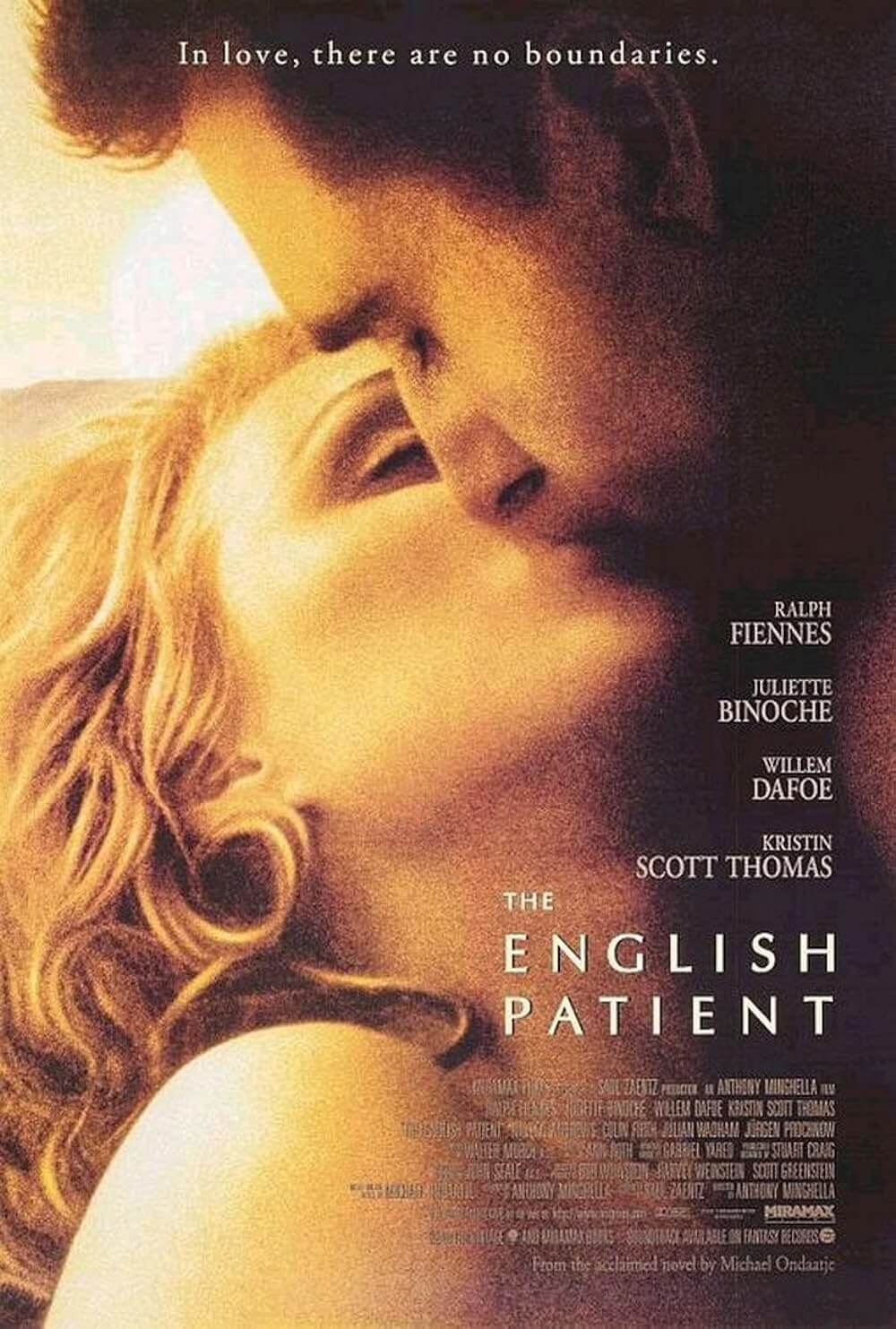

My Sister’s Keeper

By Brian Eggert |

Do children have the right and know-how to determine their medical future? Shouldn’t youngsters be able to say no when their parents opt them into medical procedures they no longer want? How can children know what’s right for them, versus something they don’t want but need? How far does parenting “for the good of the child” extend? My Sister’s Keeper presents a curious legal and moral dilemma but never provides answers to these questions. Correction: Answers are provided, but once the decisions are made, they no longer matter. Allow me to explain.

Kate (Sofia Vassilieva) has acute promyelocytic leukemia, which she’s had since she was 5, and she will inevitably die unless her sister, Anna (Abigail Breslin), donates a kidney to save her. In fact, Anna was genetically designed by way of in vitro fertilization to be her sister’s spare part depot—a plot conceived of her parents, Sara (Cameron Diaz) and Brian (Jason Patric), and their doctor. But the 11-year-old Anna doesn’t want to be poked and prodded anymore. She doesn’t want to live the rest of her life at risk because she only has one kidney. Anna’s been hospitalized several times from extractions of blood and bone marrow, and now she wants medical emancipation.

Enter hotshot lawyer Campbell Alexander (Alec Baldwin), whose layered role eventually explains why he takes on Anna’s case for her mere $700 savings. They sue for medical privileges over Anna’s body, for her right to decline potential harm from the procedures that would save her sister. The case, from a legal standpoint alone, intrigues plenty, not to mention the drama that ensues. Their fiery mother, who’s done everything, including conceiving another donor child to save Kate, doesn’t understand Anna’s selfishness, and she’s angry about it. But isn’t it rather selfish to not think of Anna’s feelings about being chopped up against her will? And then there’s Kate and Anna’s troubled brother Jesse (Evan Ellingson), who’s having his own problems. Still, neither his parents nor the script bothers explaining his curious disappearances into the inner city, where he watches prostitutes stroll by. Perhaps he just likes the attention he’s not getting at home.

Of course, the story plays out in episodic form, taking the structure of the bestselling novel by Jodi Picoult that jumps around as the melodrama demands. A pleasant interlude in the middle tells us about how Kate meets Taylor (Thomas Dekker), a patient like her who becomes her boyfriend. The movie’s chapters center on specific characters, but it doesn’t have an ending or any sense of resolution for the questions asked. By the time a verdict is reached, Kate’s dwindling health is no longer the family’s concern, so the decision means nothing. There were hints of soapboxing, such as the nods to how stem cell research could probably fix all this, which unavoidably conflict with Kate’s spirituality. Yet, these ideas could have been fleshed out further as a needed social commentary.

The performances are impressive. Breslin continues to show how mature yet childlike she can be; hopefully, she grows into a full-fledged actress someday, rather than just awkward like so many child actors become. Baldwin starts hard-edged, but he shows his soft side eventually, reminding us how fine an actor he is. Diaz was perhaps miscast, as she always feels like she’s acting no matter the role; she’s certainly valuable in those maniacal overprotective mother scenes, but when she’s meant to be soft, her performance becomes artificial. The real surprise was Vassilieva, who could earn herself an Oscar nomination for her painfully authentic role as the dying cancer patient. Likewise, Joan Cusack, not playing a total weirdo for once, gives an impressive cameo-sized performance as the emotionally broken judge presiding over Anna’s case. Despite these welcomed flourishes, something about the movie just doesn’t sit well as time goes on.

Maybe it’s the downer ending, or the near-constant narration that explains what it all means and prevents us from finding our own connections, but My Sister’s Keeper comes very close to being a truly satisfying tearjerker and just barely misses. This is unexpected, coming from director Nick Cassavetes (The Notebook), who wrote the screenplay along with Jeremy Leven. Instead of genuine feeling throughout, what you get is a good cry from plenty of TV movie clichés. You see them coming long in advance, fully anticipate them, and when they arrive, your tear ducts burst and the waters flow. That we know we’re being manipulated but reach for the Kleenex anyway attests to the effectiveness of the otherwise overt sentimentality, but doesn’t leave us feeling good about it afterward.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review