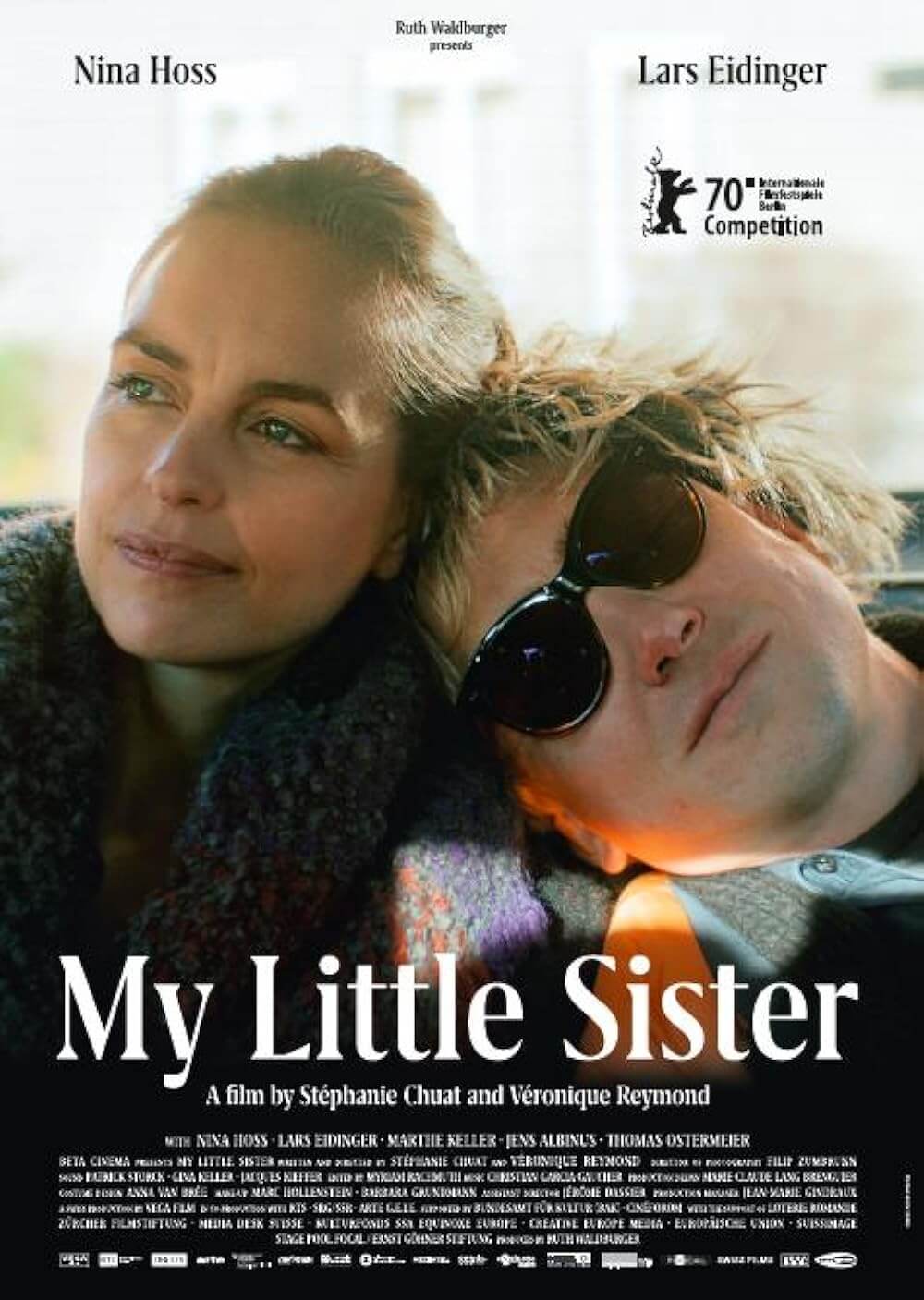

My Little Sister

By Brian Eggert |

My Little Sister (Schwesterlein) merges a drama about the bonds between two adult siblings with a story about a terminal illness. It has every potential to become an overly sentimental and cliché work of obvious heartstring-pulling. But this isn’t My Sister’s Keeper (2009), nor even just a passable example like this year’s Our Friend. Refreshingly, the writer-director team of Stéphanie Chuat and Véronique Reymond tackle the material’s depiction of midlife crises, cancer, and complicated family dynamics with a rare kind of dignity. This Swiss film gives us a natural, thematically rich, and beautifully acted treatment instead of the usual schmaltz and heavy-handedness associated with such subject matter. Stars Nina Hoss and Lars Eidinger elevate the story and give performances that capture the despair, anger, and hopelessness that a grave illness can spread.

The first scenes show Lisa (Hoss), the title’s little sister, donating bone marrow to Sven (Eidinger), her older brother by about two minutes, and a famous gay actor on the Berlin stage. Lisa is a talented playwright from Berlin who has moved to Switzerland with her two children to follow her husband, Martin (Jens Albinus), the director of an elite boarding school in the resort town of Leysin. She has taken a hiatus from writing to teach at her husband’s school, an occupation she finds unfulfilling. As Sven’s cancer grows progressively worse, Lisa tries to care for him from a distance, making the trip to Berlin whenever possible. But with Sven needing more care, Lisa cannot rely on their mother, Kathy (Marthe Keller), who smokes, keeps a messy house, and has nothing but excuses for her awful behavior (at one point she tells Sven that she would rather die than try to fight cancer in his condition).

With that, Lisa moves her brother from Berlin to Switzerland to stay with her family. His presence comes after a long time apart, reminding Lisa both of why she stopped writing—on the day of Sven’s diagnosis no less—and what makes her happiest. Both creatives are at their best when acting or writing, but Sven’s worsening state prevents him from returning to the stage, and Lisa is determined to write something for him. She resolves to create a mature, dialogue-based take on the Grimm fairy tale, Hansel & Gretel, projecting their own experiences with their mother onto the story of two children lost in the woods, facing an evil witch. They’ve always been like this, on their own, their truest selves in each other’s presence. And so, the prospect of losing her Hansel frightens Lisa.

Hoss’ performance is brilliant. She’s a performer whose face shows a lifetime of experience, and she’s incapable of rendering a false emotion. And yet, she’s often playing characters who wear masks to conceal themselves. Watch any of her collaborations with German filmmaker Christian Petzold—see Yella (2007), Jerichow (2008), Barbara (2012), or Phoenix (2015)—and you find an actress whose default mode is entrenched in dimensionality. Her role becomes increasingly complex in the second half when Sven’s body rejects the bone marrow transplant and begins to form sores everywhere. At the same time, Martin renews his contract at the school, which will keep Lisa away from Berlin, where she feels most at home. These factors conspire to send Lisa into a breakdown, reacting with rage and denial, as though it’s her and Sven against the world, and everyone else represents the dark and dangerous woods. When she finally cracks up by declaring “Fuck you all!” and kicking a dumpster, it’s a burst of anger followed by an oddly serene moment of composure.

Hoss’ performance is brilliant. She’s a performer whose face shows a lifetime of experience, and she’s incapable of rendering a false emotion. And yet, she’s often playing characters who wear masks to conceal themselves. Watch any of her collaborations with German filmmaker Christian Petzold—see Yella (2007), Jerichow (2008), Barbara (2012), or Phoenix (2015)—and you find an actress whose default mode is entrenched in dimensionality. Her role becomes increasingly complex in the second half when Sven’s body rejects the bone marrow transplant and begins to form sores everywhere. At the same time, Martin renews his contract at the school, which will keep Lisa away from Berlin, where she feels most at home. These factors conspire to send Lisa into a breakdown, reacting with rage and denial, as though it’s her and Sven against the world, and everyone else represents the dark and dangerous woods. When she finally cracks up by declaring “Fuck you all!” and kicking a dumpster, it’s a burst of anger followed by an oddly serene moment of composure.

Hoss’ incredible turn should not overshadow Eidinger—from Clouds of Sils Maria (2014) and Personal Shopper (2017)—whose portrayal of pain and despair aligns with the film’s realistic approach. Sven holds onto the desperate belief that he will act again, and his eventual self-destruction when he realizes that won’t happen proves devastating. When he takes a sharp decline, the filmmakers capture these scenes with unflinching reality. The camerawork by cinematographer Filip Zumbrunn feels observational and unfussy, echoing the team’s previous work in documentary. Christian Garcia-Gauche’s score, including long sections of German opera, avoids over-accenting heightened emotional moments. The music doesn’t remind us how to feel as a Hollywood production might. Rather, non-diegetic sounds tend to fade away in panicky hospital scenes, while the score remains absent for the film’s biggest emotional blowouts. Fortunately, the performances speak for themselves.

U.S. audiences rarely get to see Swiss films imported, but My Little Sister has made the rounds on the festival circuit before becoming Switzerland’s submission for the Best International Feature Film at this year’s Oscar ceremony. Unfortunately, Chuat and Reymond were unduly overlooked for the nomination. Their picture of deep-rooted bonds and codependence makes the familiar trappings of family drama feel more potent and open-hearted; it never risks feeling disingenuous. Shot on location in Berlin and the Swiss Alps, there’s a natural beauty to the film as well. And aside from a few moments of arch behavior, including a paragliding scene and a reckless nightclub visit, the grounded proceedings supply Hoss and Eidinger with a showcase for their talents. They play their characters’ bond with humor, understanding, frustration, and something unspoken only close siblings could describe, which makes watching My Little Sister a rich and intimate experience.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review