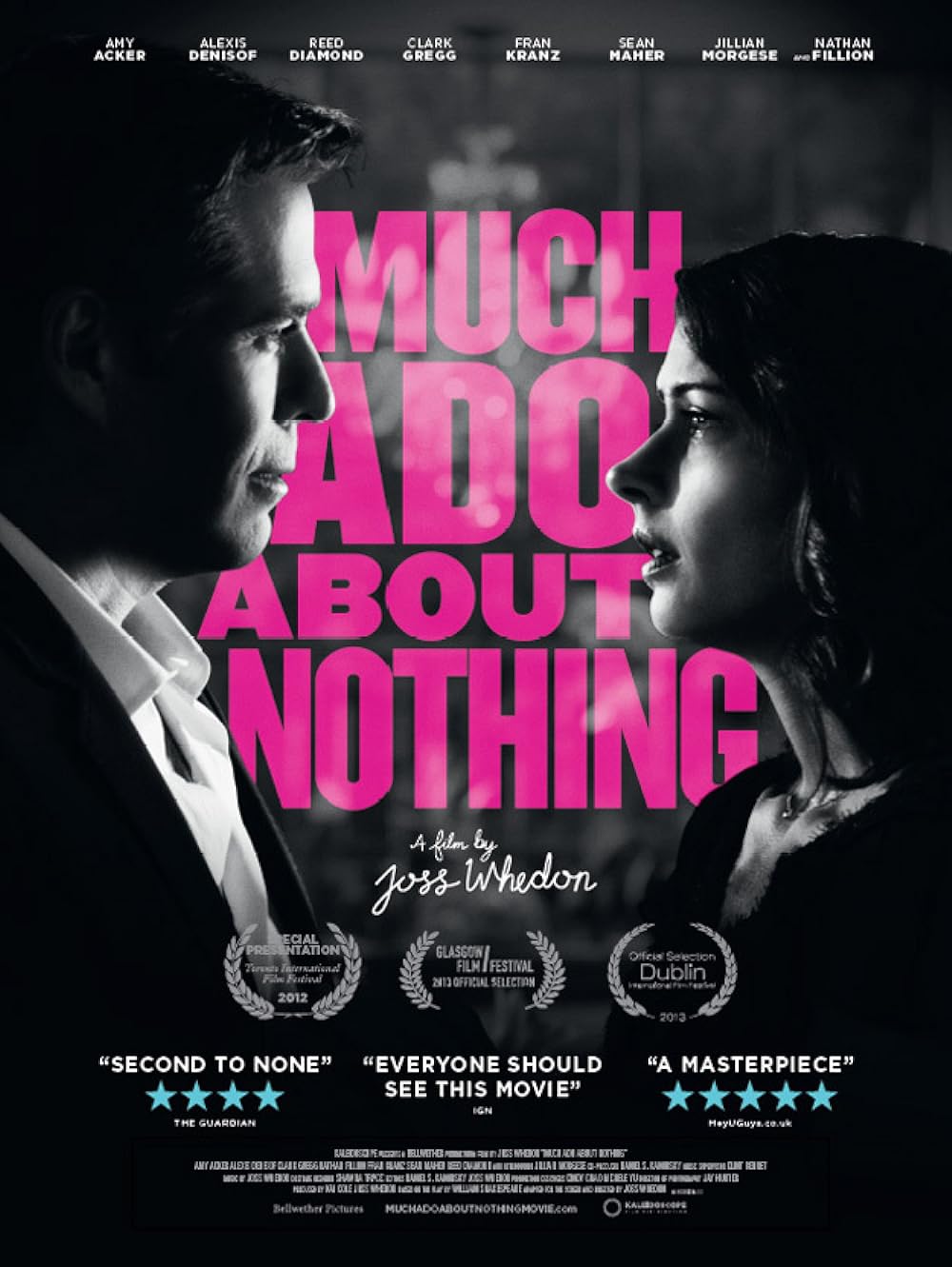

Much Ado About Nothing

By Brian Eggert |

Joss Whedon’s characters love to talk, and in their talk, they love to engage in battles of wit. From the verbal duels between superheroes in The Avengers to the playful banter between lovable rogues in his canceled-too-soon space cowboy TV series Firefly, Whedon’s characters are most fascinating when engaged in a playful sparring match of dialogue, and less so when pure action takes over. It’s only natural, then, that Whedon would set aside his jokey vampire hunters, intergalactic rejects, and the Marvel Universe to embrace the work of William Shakespeare. Like the Bard, Whedon’s predilection for snappy banter and a search for self-understanding has driven his work. With Much Ado About Nothing, Whedon strips down to the bare structure of what he’s been writing about for years, without the benefit of the fanboy pretense, to explore characters who love each other, especially those whose love connection is uneasy either because forces have aligned against them or they don’t yet realize how they feel.

The film, shot in 2011 during Whedon’s vacation after completing principal photography on The Avengers and released on the festival circuit in 2012, is beautifully informed by a text about the film from Titan Books, titled simply Much Ado About Nothing. The interviews and backgrounds referenced in this review are borrowed from the book (available on Titan’s website), which contains an introduction by Whedon, his full script, and a lengthy, enlightening interview. In the book, Whedon talks about how he came to the realization that throughout his career, he’d been writing Shakespearian characters with similar conflicts and romances, intentionally or not, inspired by material written some 400 years ago. And with the help of the book, although not exclusively because of it, one appreciates how, without the need for blockbuster production values or special FX, Whedon’s adaptation of Much Ado About Nothing creates a raw thematic template for his entire oeuvre thus far.

Indeed, his production was filmed in what Whedon calls “noir comedy” black-and-white (Whedon considers it along the lines of Billy Wilder’s The Apartment). He completed principal photography in just 12 days, shooting on a shoestring budget—all of this a far cry from his megabudget projects. What’s more, the sole locale was Whedon’s gorgeous Santa Monica home designed by his architect wife, Kai Cole. Her focus as a designer was to have a flow between rooms, a connection where children could crawl and guests could move about freely. Colleagues would be encouraged in their artistic endeavors by the unhindered movement in the space. “The idea of this eclectic, artistic space was important,” says Whedon. Unintentionally, the home became the ideal setting for a play adaptation in which characters could engage in a walk-and-talk without feeling restricted by inhibiting walls or doors. When the house was finished, Cole suggested that they film their long-discussed adaptation of Shakespeare’s play there instead of a planned vacation to Italy.

Whedon grew up around plays, his mother directing seasons of summer stock when he was just a boy. His family read Shakespeare regularly as a Thanksgiving tradition, and he soon became “obsessed” with the playwright, at first because of the pure humor found in something like Much Ado About Nothing, but later because of Shakespeare’s deeper resonances. And though Whedon would never direct a stage play, on the set of Buffy the Vampire Slayer, he and his cast recorded casual readings of Shakespeare plays on the weekend. Given his work, it’s easy to understand why Whedon chose this play to adapt above all others. For one, the lack of verse throughout makes the transition to a modern setting much easier, despite the Shakespearian rhetoric throughout. In this most prose-heavy of the Bard’s texts, Whedon is able to draw on and underline what has always been present in his work—his chatty, mischievous style of conversation.

Following the courtships of two would-be couples, the story, for those unfamiliar, concerns devoted bachelor Benedick (Alexis Denisof) and his single-minded female opposite Beatrice (Amy Acker); and also a more infatuated pair, Claudio (Fran Kranz) and Hero (Jillian Morgese), who are destined for love yet tested by meddling parties. The villainous Don John (Sean Maher) schemes to thwart the coupling of Claudio and Hero, but his plot is finally exposed by inexpert constable Dogberry (Nathan Fillon). Meanwhile, friends and family of Beatrice and Benedick arrange for the two to realize their constant griping and battles of wit are actually symptoms of their mutual, unrealized, but wholly requited love for one another. The planned marriage of Claudio and Hero seems doomed, until, of course, in the final scenes, it is not, and both couples are joined. With all the frivolities of Shakespeare’s best comedies and the resounding profundity of his tragic dramas, the story is arguably one of his most accessible.

More than just a story of lovers uniting and villains receiving their comeuppance, Much Ado About Nothing has a rich wealth of meaning. Whedon admits to acknowledging and, with a touch of feminism and eroticism, emphasizing the implications through the title’s double entendre—“Much Ado About An O Thing”. The inference is such that women were believed—from the Elizabethan Era and beyond until just recently, historically speaking—to have nothing to say if only because of their womanhood, the “O” of the pun a reference to the vagina. Progressive as he often was, Shakespeare implies his feminist sympathies in Beatrice’s independent streak and her outright autonomy of mind, her having no use for men, save for the equally independent Benedick. As always, there are layers behind Shakespeare’s title in that the play and Whedon’s film are not about “nothing” at all. Rather, the material is about everything, which is to say everything important—family, romance, marriage, and the awakening to understand not only oneself but the embrace of love. Sex should not be excluded from this list, as Whedon incorporates sly uses of sensuality to underscore how Shakespeare disguised such themes in his title and his prose.

The adaptation, it must be said, is as brilliant a modernization of Shakespeare’s work as one is ever to find on film. As film versions of this play in particular go, there are now only two worth mentioning: Whedon’s, and the 1993 version by Kenneth Branagh. Besides reducing the play by a third and altogether removing superfluous characters, Whedon’s adaptation arrives with energy in the humor, extending from the verbal to the physical in more than one scene. Acker’s pratfall down the stairs and Denisof’s clumsy covert antics are hilarious. And while Acker (from Whedon’s co-written The Cabin in the Woods) and Denisof (from Buffy and Angel) may not compare to the thespian heights of Branagh and Emma Thompson, the overall casting of American-accented Whedon regulars is wonderful. Kranz (also in The Cabin in the Woods) makes for a deeply vulnerable “yutz”; Maher (from Firefly) is a quintessential villain; and Fillon (also Firefly) makes a hilariously sympathetic Dogberry, complete with charming malapropisms. The sole flat note is Riki Lindhome’s uninspired Conrade.

Whedon’s Much Ado About Nothing could hardly be called traditional and should be cherished for its innovations. Consider how his first scene shows a very modern take on Benedick and Beatrice, suggesting a sexual encounter between them before the events of the story take place, thus making their relationship even more complicated than we always thought. These shots also suggest a casual visual style reminiscent of early 1990s independent cinema (such as Clerks) that carries on throughout the film for an informal martini-and-smartphone-laden version of Shakespeare’s play, fulfilled by the rich, amusing, and affecting performances. Further reading on the subject should be sought in Titan Books’ release, but one need not read about the film to appreciate its more basic rom-com pleasures, just as one need not be a Shakespeare enthusiast to find something relatable within the material. Whedon has rendered the play so plainly funny, and yet because he never sacrifices its higher purpose, he has reinvigorated its depth and resonance for an entire generation of viewers who might not have been exposed to its complexities otherwise. To keep Shakespeare timely is the task sought after by every new adaptation, and Much Ado About Nothing belongs on a short list of films to celebrate the relevance of Shakespeare in cinema.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

Thank you for visiting Deep Focus Review. If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your movie watching—whether it’s context, insight, or an introduction to a new movie—please consider supporting it. Your contribution helps keep this site running independently.

There are many ways to help: a one-time donation, joining DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or showing your support in other ways. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review