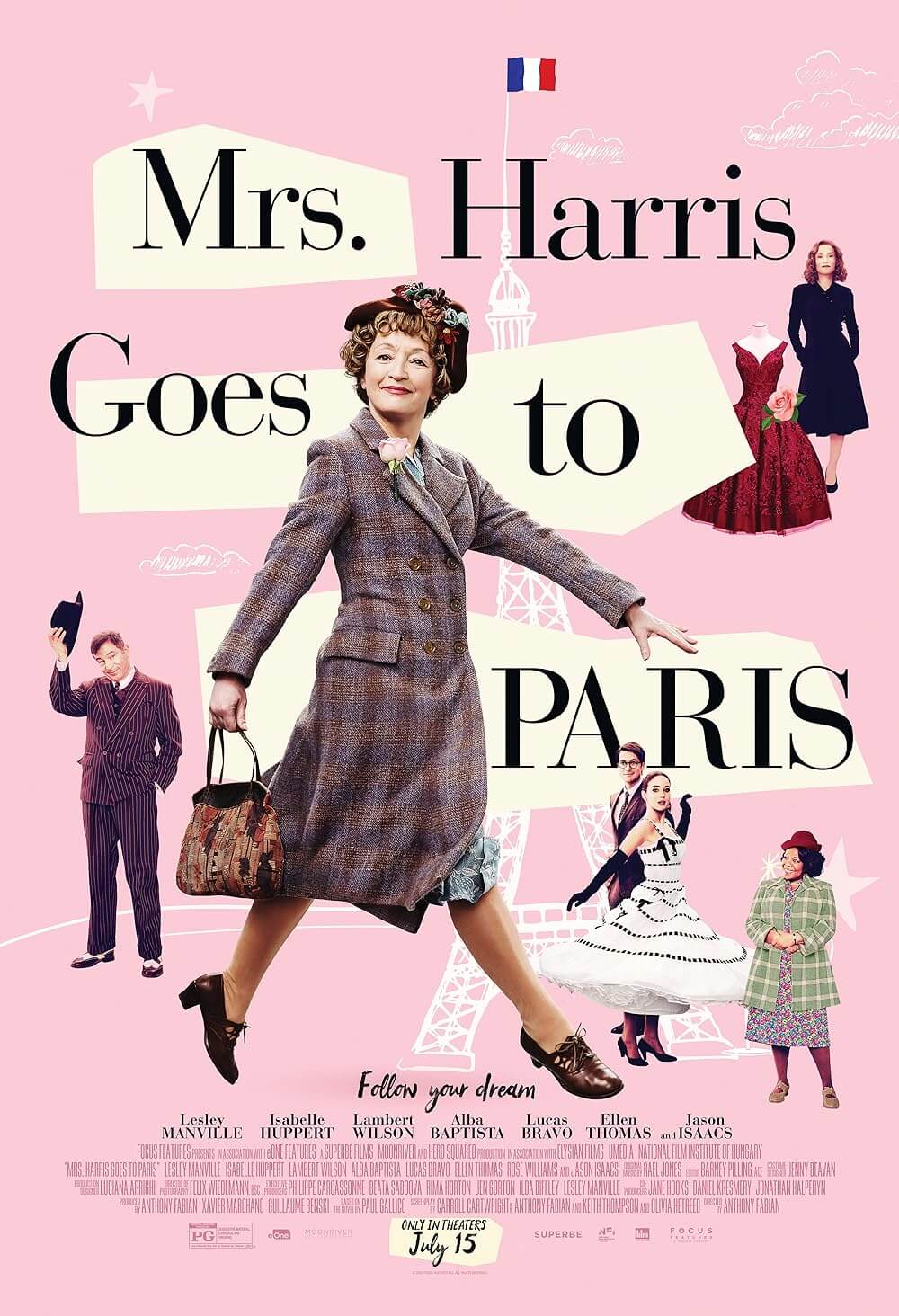

Mrs. Harris Goes to Paris

By Brian Eggert |

Mrs. Harris Goes to Paris is the blithely playful title for director Anthony Fabian’s charming Cinderella story set in the world of 1950s haute couture. It’s a film about a romantic, played by Lesley Manville, whose daydreams mount into a heartwarming tale that’s bound to cause laughter, swooning, and tears of joy. Manville lends her boundless humanity to Ada Harris, a widowed cleaning lady from London accustomed to selflessly maintaining the lives of others. After seeing a Christian Dior dress in a client’s home, she imagines owning one herself, and as her superstitions and providence align, she gets the opportunity. Although the story hits familiar beats and ends up, in a roundabout way, where one might predict, Fabian’s generous treatment of his subject and characters reaches beyond superficial beauty or storybook simplicity. Instead, the film considers an uncommon and winning blend of fantasy, reality, and even philosophy. While Disney continues to mine classical fairy tales in animation and live-action to hollow effect, here’s a film that transports the viewer into a twinkling fable, yet it never forgets about the emotional integrity of its characters, even while delivering a gleeful delight.

Adapted from the book by Paul Gallico, who wrote an entire series of “Mrs. ’Arris” stories that follow the titular character around the world on modest adventures, the film is a classically structured enchantment. Fabian, who co-wrote the script alongside Carroll Cartwright, Keith Thompson, and Olivia Hetreed, imbues the material with a dreamy sense of fantasy-come-true. Set in 1957, Mrs. Harris lives a routine life. She cleans the homes of a few clients each week, ranging from a well-to-do bachelor (Christian McKay) to a flighty ingénue (Rose Williams). Each morning before daylight, she walks along the luminescent Albert Bridge and gazes down at the Thames, yearning for more. When she’s not cleaning, she’s either alone at home or out with her fellow cleaning lady, Vi (Ellen Thomas), or chatting with the incorrigible pub regular, Archie (Jason Isaacs). Her husband disappeared in Poland in 1944, and she’s been alone ever since. Somehow, she has held out hope that he’s still alive. But when the film opens, she receives a package containing his wedding ring and a final confirmation of his death. Still, there’s room to dream. Another client, the shallow Lady Dant (Anna Chancellor), spends £500 on a new Dior dress instead of paying Mrs. Harris her back wages. Nonpayment aside, the sight of the gown leaves Mrs. Harris overcome and transported by its beauty.

Expect leaky tear ducts early in the proceedings, as a series of fateful events align the universe in Mrs. Harris’ favor. She saves up enough money to travel to Paris overnight and buy a House of Dior dress for herself. Of course, it’s not quite that simple, as explained by the snooty manager, Claudine Colbert (Isabelle Huppert), the evil stepmother of Dior. For starters, the highfalutin Colbert looks down on Mrs. Harris for her inferior class appearance and quickly assesses that she doesn’t belong. Several others come to her rescue, including Dior accountant André Fauvel (Lucas Bravo) and model Natasha (Alba Baptista). Also in attendance at the showing is the widower Marquis de Chassagne (Lambert Wilson), who personally invites Mrs. Harris inside, seeing that she’s come a long way and, what’s more, has the cash in hand for a dress. But Dior’s highbrow clientele cherish their exclusivity and stick their noses up at Mrs. Harris, who learns she must undergo weeks of fittings before her purchase is complete. With the further kindnesses from Fauvel and Natasha, Mrs. Harris arranges to stay and sample Parisian nightlife while waiting for the Dior staff to complete her dress.

Each of the main characters mentioned in the preceding paragraph could have been written as one-note constructions. Fauvel and Natasha might have been nothing more than good-hearted employees who take sympathy on our protagonist, helping her along; the Marquis seems like an obvious love interest; and Colbert is the apparent elitist and resident villain. In another film, those tropes would do. But Fabian has something more well-rounded, even novelistic in mind for Mrs. Harris Goes to Paris, and the actors are capable of much more dimensionality than their first impressions suggest. A strain of philosophy emerges as Fauvel and Natasha share their love of existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre, whose theories about the person behind the exterior inform Fabian’s treatment of character here. Although it’s somewhat on the nose to have an open discussion of the philosopher occupying a scene or two, it nonetheless pays off on emotional and dramatic turns when the characters prove to be more than their occupation. This goes for Mrs. Harris as well. Although the character was previously played in a TV movie by Angela Lansbury in 1992, and various other adaptations, here’s hoping Manville launches a new franchise—after all, Gallico wrote four novels featuring Mrs. Harris.

Each of the main characters mentioned in the preceding paragraph could have been written as one-note constructions. Fauvel and Natasha might have been nothing more than good-hearted employees who take sympathy on our protagonist, helping her along; the Marquis seems like an obvious love interest; and Colbert is the apparent elitist and resident villain. In another film, those tropes would do. But Fabian has something more well-rounded, even novelistic in mind for Mrs. Harris Goes to Paris, and the actors are capable of much more dimensionality than their first impressions suggest. A strain of philosophy emerges as Fauvel and Natasha share their love of existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre, whose theories about the person behind the exterior inform Fabian’s treatment of character here. Although it’s somewhat on the nose to have an open discussion of the philosopher occupying a scene or two, it nonetheless pays off on emotional and dramatic turns when the characters prove to be more than their occupation. This goes for Mrs. Harris as well. Although the character was previously played in a TV movie by Angela Lansbury in 1992, and various other adaptations, here’s hoping Manville launches a new franchise—after all, Gallico wrote four novels featuring Mrs. Harris.

No stranger to cinematic depictions of high fashion after her Oscar-nominated role in Phantom Thread (2017), Manville, who also executive produced, gives one of her most endearing performances in Mrs. Harris Goes to Paris. Her acting has all the dimension and layering of her appearances in Mike Leigh’s cinema, and that presents a compelling series of contrasts given the fanciful nature of the story. Manville endears us to Mrs. Harris, rendering every characteristic and emotion true, and her distinctly British sense of humor supplies a constant source of laughs. When she’s happy, we’re brimming along with her. If she feels slighted, we feel it through her performance and the other characters who empathize with her. When fate works in her favor, again and again, it’s less a contrivance than an overwhelming pleasure that fills us with happiness. Under Fabian’s pitch-perfect control of tone, each of the actors manages to maintain emotional reality within the fairy tale quality of the story, offering a chimerical turn of events that never betrays the integrity of their characters or strains believability. This weaves elegantly into the film’s Sartrean theme about Dior’s need to move from an exclusively Paris-based house for the super-rich, who often do not pay their bills on time or at all, to a brand that’s accessible to everyone.

The look of the film balances reality and fantasy as well. Cinematographer Felix Wiedemann captures the streets of Paris littered with refuse from a garbage worker’s strike. Kindly winos in a depot and Mrs. Harris’ modest apartment have the gruff reality of something more grounded and earthbound. In contrast, the film quickly loses itself in our protagonists’ starry-eyed bliss in the presence of a Dior dress. When she sees such beauty, Mrs. Harris loses herself for a moment. Fabian and Wiedemann borrow Spike Lee’s oft-used double dolly shot, where the camera and actor rest on the same dolly that moves through a space, creating an impression that the character is being pulled toward something with a sense of disembodied purpose. Brief flourishes such as this break from the otherwise straightforward historical setting and transform the film into a euphoric experience. The filmmakers see fashion through Mrs. Harris’ subjective perspective, and it’s contagious. Wiedemann shoots the lovely and varied gowns from the period, provided by the House of Dior no less, with evident affection for their refinement. A fashion exhibition sequence early on rivals the one in George Cukor’s The Women (1939), and seen through Mrs. Harris’ eyes, it’s blissful.

At the core of Mrs. Harris Goes to Paris is a humanist message about seeing beyond class and labels. Colbert asks Mrs. Harris, “How will you give this dress the life it deserves?” But it’s not about living up to the Dior standard; it’s about recognizing that everyone deserves to feel like they belong in such luxury. The filmmakers have integrated that theme into a critique of class and storybook tropes by applying them to the workaday protagonist. Indeed, the third act introduces conflict that threatens to make Mrs. Harris the fairy godmother of her own story, but an airy solution delivers a magnificent ending. If you’re not a sloppy mess by the final scene, laughing and crying along with its felicity, seek help. Anchored by Manville’s beautifully nuanced and sunny performance (and those of the supporting cast), assured direction by Fabian, and a gorgeous production design by Luciana Arrighi, Mrs. Harris Goes to Paris is a surprise and a pleasure. Its warmth and tenderness result in a marvelous, romantic, touching, funny, and deeply satisfying film that’s not to be missed.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review