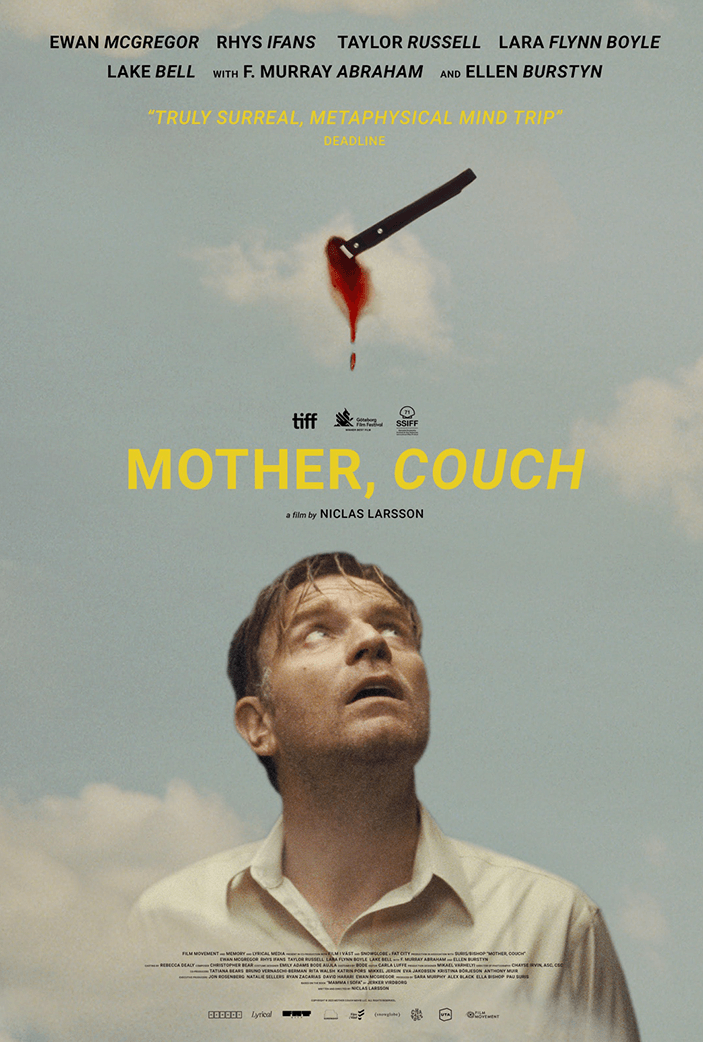

Mother, Couch

By Brian Eggert |

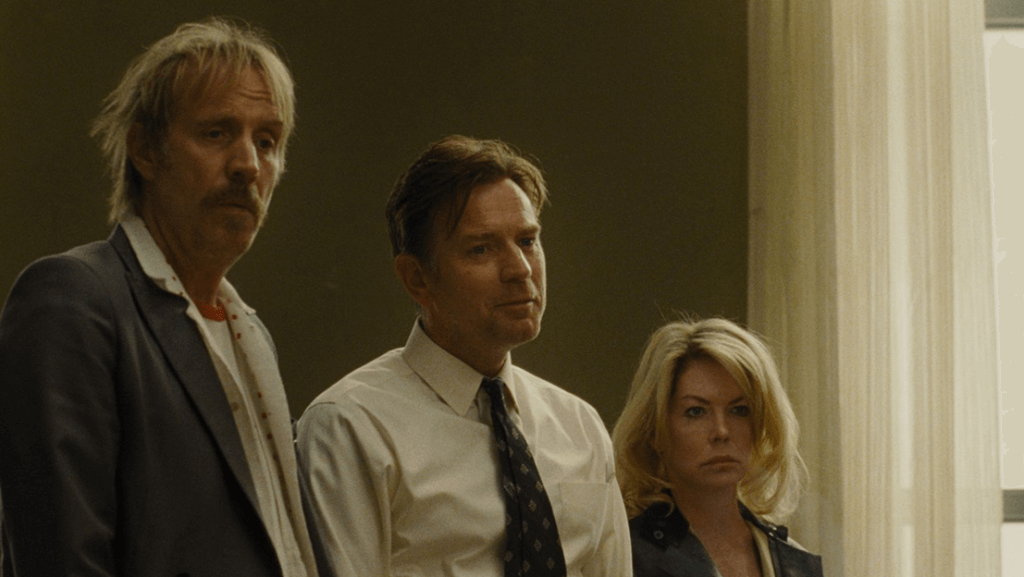

“You all seem so broken.” That observation is made by Taylor Russell, who plays Bella, an employee at Oakbend’s Furniture, her family’s store. Bella is a peripheral figure in Mother, Couch, an absurdist, high-anxiety comedy that marks the feature debut of Swedish actor-turned-director Niclas Larsson. But she’s also a mysterious and wise-beyond-her-years observer with a knowing sense of the people around her. She quickly sizes up David (Ewan McGregor), a nervous people-pleaser who remains central in the film. David and his older brother, Gruffudd (Rhys Ifans), with whom Bella vaguely flirts, have stopped at Oakbend’s store with their mother (Ellen Burstyn). In a rush, David has a cake to pick up, a birthday party to attend, and a wife and daughter waiting for him. So, when his mother sits on a green couch and stubbornly refuses to leave for hours, even days, his nerves fray, underlining the tensions in his family and, as Bella observes, his broken emotional state. The quirky, irrational situation offers much metaphoric potential. However, as the film carries on, the symbolism proves trite and self-consciously peculiar, and the whole endeavor never pays off in dramatic terms.

An adaptation of Jerker Virdborg’s novel Mamma i soffa (Mom on Sofa), Larsson’s film feels like an approximation of Charlie Kaufman’s work, albeit without the identity-crushing themes found between Being John Malkovich (1999) to I’m Thinking of Ending Things (2020). There’s a familiar twinkle and paranoia in Christopher Bear’s score and a particular brand of formal rambunctiousness to Chayse Irvin’s cinematography, recalling how directors Spike Jonze and Michel Gondry handled Kaufman’s scripts. Whatever drove Larsson to adapt Virdborg’s text, one suspects that its marketable similarity to Kaufman, along with Luis Buñuel’s output, played a factor. To be sure, it’s difficult to read Mother, Couch’s logline and not think of Buñuel’s The Exterminating Angel (1967), about dinner party guests who cannot leave, or The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972), about a dinner that is perpetually delayed. Larsson’s film, with its plot about a mother who refuses to leave a store, may earn comparisons to the great surreal cinema, but it hardly deserves the same distinction.

The story unfolds during a frantic day or so where David attempts to get a handle on his unraveling life, starting with his mother’s refusal to leave the couch. “I’m not coming,” she tells him. But why? “I’m just not going with you,” she explains with characteristic unsentimentality. There’s never more explanation offered, and David finds himself trapped in an impossible situation, topped with an existential dilemma. Should he and Gruffudd attempt to move her, she promises self-harm. Armed with a sharp letter opener, she also slashes at David at one point when he approaches, leaving a gash in his hand. Later, the knife ends up in his back in a moment that’s more symbolic than substantive. And even as hours pass and closing time arrives, David won’t call the police or an ambulance, even though his sister Laura (Lara Flynn Boyle) thinks they should force her off the couch. Fortunately, Bella proves surprisingly accommodating, suggesting their mother and even David could sleep there until they resolve the situation.

The whole situation supplies an analogy for David’s psyche, I suppose. He remains so preoccupied with his family and maintaining appearances that he ignores or actively avoids addressing his issues, even though he yearns for clarity. A consummate compartmentalizer and minimizer of conflict, David misreads every situation and second-guesses every choice, trying to make everything right. But he, even more than his siblings, has hang-ups about his mother, who had three children with three different fathers and neglected David above all. Even as certain family behaviors and dynamics prove relatable, much about the family doesn’t make sense. The siblings seem to be in close communication—close enough to take their mother furniture shopping and attend a birthday party together. Still, they also talk about being estranged, with Gruffudd having been married recently, though David just finds out about it. Allusions to their complex history never quite clarify, even if the dysfunctional behavior is recognizable.

The whole situation supplies an analogy for David’s psyche, I suppose. He remains so preoccupied with his family and maintaining appearances that he ignores or actively avoids addressing his issues, even though he yearns for clarity. A consummate compartmentalizer and minimizer of conflict, David misreads every situation and second-guesses every choice, trying to make everything right. But he, even more than his siblings, has hang-ups about his mother, who had three children with three different fathers and neglected David above all. Even as certain family behaviors and dynamics prove relatable, much about the family doesn’t make sense. The siblings seem to be in close communication—close enough to take their mother furniture shopping and attend a birthday party together. Still, they also talk about being estranged, with Gruffudd having been married recently, though David just finds out about it. Allusions to their complex history never quite clarify, even if the dysfunctional behavior is recognizable.

Along the way, Larsson implants one frustrating and idiosyncratic wrinkle after another, building on Mother, Couch’s borderline horror appeal. F. Murray Abraham plays identical twin brothers, Marcus and Marco, Bella’s father and uncle, in a detail that suggests how siblings can be the same but also different. Bella’s presence is typical of a cipher, with alternately creepy yet inviting behavior, depending on the scene, and Taylor is terrifically inscrutable. For much of the film, the characters inhabit the drab space of Mikael Varhelyi’s production design, which establishes a long-past-its-prime store and vacant parking lot. But when Larsson follows David outside to call 9-1-1, where he has a colossal breakdown, or to take his daughter for a disastrous trip to the beach, the director relieves the claustrophobic scenario and neutralizes the tension. It’s all the more maddening when David returns to the store after these brief escapes. In the finale, the film goes full abstract with a flood sequence that, while beautifully shot, feels overwrought.

McGregor and Burstyn commit to their underwritten roles in a couple of fantastic performances, with the former conveying his character’s emotionally fraught state and the latter embodying her character’s obstinance. How they behave toward one another proves relatable, particularly in the mother’s casual disregard for others’ feelings. For her lifelong behavior, David’s mother tells him, “I can’t apologize, but will you forgive me?” Cruel ironies such as this exist throughout Mother, Couch, although the relationship between the literal and figurative remains unstable, not funny as intended, and neither satisfying nor particularly engaging. While it’s a cautionary tale about the dangers of wasting love on people who have no love to give in return, the film doesn’t balance its emotional underpinnings with its mode of storytelling. Rather, the film’s surrealism mutes the intended emotional impact, leaving Mother, Couch a fascinating but underwhelming experience.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review