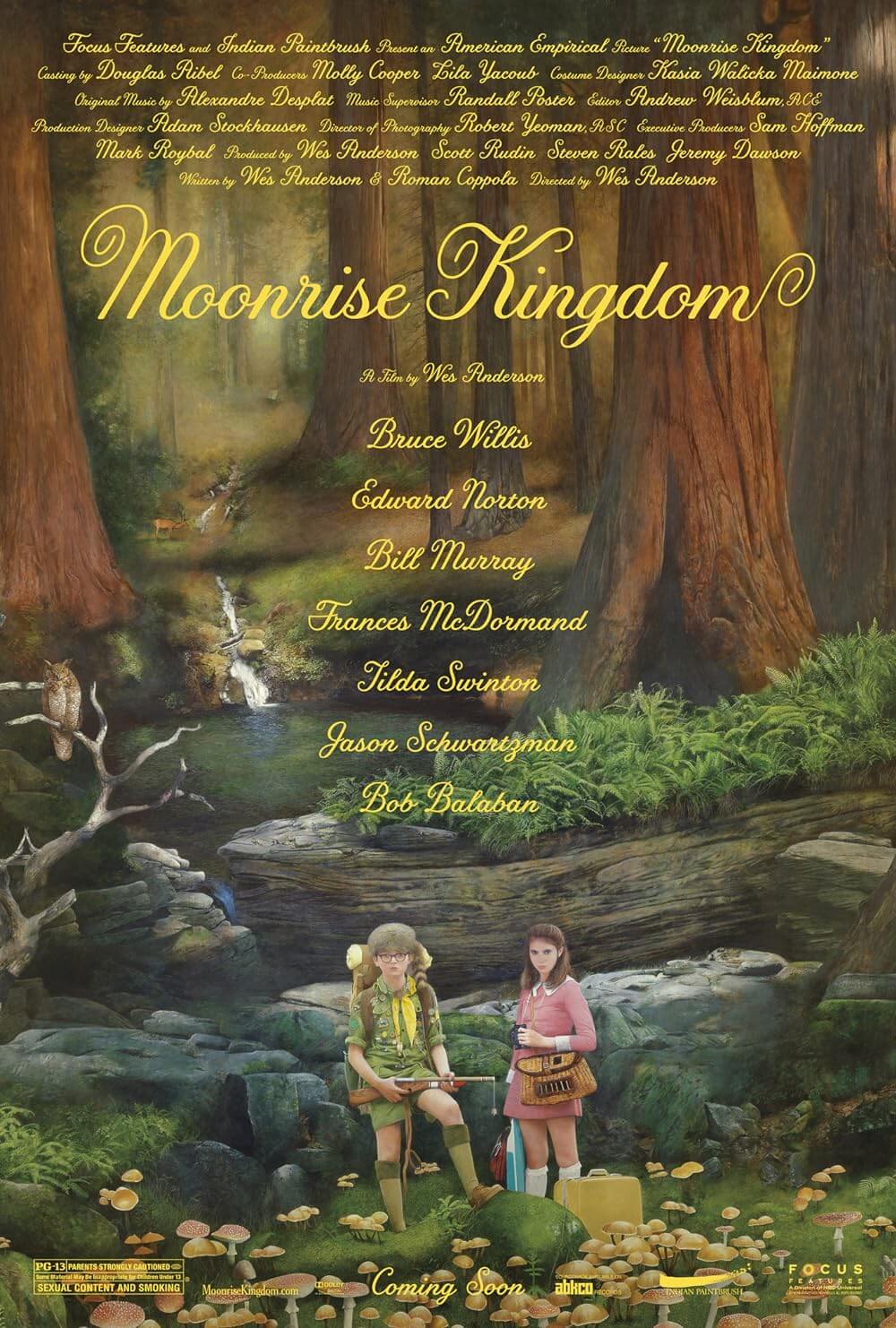

Moonrise Kingdom

By Brian Eggert |

Reliable as the tide, Wes Anderson has provided moviegoers with a string of dependably eccentric and highly stylized films. In them, we find strong emotional undercurrents beneath his meticulously crafted arrangement of symmetrical framing, bright color design, and particular attention to detail in both his formal approach and his characters. And not one Anderson film passes by without a character consumed by a similar attention to detail. In his 1996 debut Bottle Rocket, Owen Wilson’s Dignan plotted an extensive 75-year plan for his criminal career. Rushmore (1998) found the bright Max Fischer (Jason Schwartzman) able to negotiate every extracurricular activity his school offered, but unable to pass any of his classes. The Darjeeling Limited (2007) features three brothers on a trip through India, one of whom obsesses over their laminated daily itinerary. The list could go on and on. Of course, it’s a common theme in Anderson’s films that these fastidious characters sometimes overlook their emotional selves in favor of their persnickety organizational skills. Fortunately, Anderson’s films never have that problem.

A resounding example is Moonrise Kingdom, which Anderson co-wrote along with Ramon Coppola. The film is about a preteen boy and girl whose lives are regimented by such supreme precision that they’re desperate to escape with each other to their eponymously named beachside getaway. Sam Shakusky (Jared Gilman) and Suzy Bishop (Kara Hayward) live on an island called New Penzance off the New England coast. The year is 1965. An orphan, Sam spends the summer at Camp Ivanhoe learning outdoor trades with his troop of “Khaki Scouts of North America,” headed by boyish Scout Master Randy Ward (Edward Norton), who conducts daily inspections. Suzy feels locked inside her dollhouse residence, populated by three young brothers and two distant parents (Bill Murray and Frances McDormand), the latter two attorneys who sleep in separate beds and chit-chat mechanically about the day’s motions in court. Neither child is well-adjusted (then again, who is in Anderson’s films?), but a year ago, these youngsters met during a community performance of Benjamin Britten’s Noye’s Fludde and since have discovered they are soul-mates.

When they meet in an empty field at the designated time and place, Sam brings Suzy a bouquet of wildflowers and has their journey plotted on a map. They set out, guided by Sam’s expert wilderness training, he sporting thick-rimmed glasses and a fur Davey Crocket cap, and she with heavy blue eye makeup and Sunday school shoes. Together they listen to Françoise Hardy records on a portable player, explore each other’s bodies and French kiss; he pierces her ears with a fishhook, and she reads to him at night by the fire. It’s endearingly innocent, while Gilman and Hayward give incredibly confident debut performances. Their expedition is meaningful both as an act of defiance and declaration of love, but also appropriately symbolic and comically absurd for an Anderson film, since, after all, they’re trying to escape to another part of a modestly sized island. It is the imperative and tender purity of young love that brings these two together and cements our investment in their future. Once they arrive at their destination cove to camp and dance and kiss, the viewer never wants these nostalgic moments to end.

Meanwhile, they’re tracked by Suzy’s parents, downhearted local cop Captain Sharp (Bruce Willis), and Scout Master Ward with his troop of vengeful scouts, none of whom like Sam very much at first. Schwartzman and Harvey Keitel also appear as senior scouts. The younger scout clan, however, mobilizes in full preparedness with knives, bows, and arrows, and a big wooden stick with nails driven through the club-like end—just in case Sam puts up a fight. The children in the film talk like dramatic characters from one of Max Fischer’s plays, using theatrical dialogue and making direct eye contact whenever they speak. When Sharp tries to inform Sam’s foster parents of the situation, the foster father explains Sam isn’t welcome back; meaning, he’s to return to Social Services (Tilda Swinton), a cold bureaucrat named after her post. But the power of Sam and Suzy’s love overcomes even the adults in Moonrise Kingdom, who find the young lovers about two-thirds through the film and at first scorn them. Soon the adults realize how handing Sam over to Social Services and separating the two only reflects the unfulfilled aspects of their own lives.

This is a lovingly told, deeply affecting story that voyages into fantasy almost as much as Anderson’s last, Fantastic Mr. Fox (2009). The film’s deadpan delivery of dialogue and quick-witted humor offer no end of laughs, just as the quirky 1960s-inspired visual flourishes give the production a unique place in the director’s body of work. With every Anderson film, there’s a staged quality to the production, complete with calculated camera movements and artificial designs reminiscent of Eric Chase Anderson’s delicate paintings. Here those qualities contain certain storybook airs, and in more than one instance, Anderson evokes The Night of the Hunter (1955) in terms of his mise-en-scène, particularly during the church scenes in the hurricane-blown climax, as foretold by narrator Bob Balaban. Every inch of the frame is packed with fascinating details, from the costumes designed by Kasia Walicka-Maimone to the sets designed by Adam Stockhausen and Kris Moran. For the sixth time, Anderson teams with cinematographer Robert Yeoman, who makes every carefully balanced, sepia-toned shot worthy of framing. And for the second time, Anderson teams with composer Alexandre Desplat, whose light score imbues whimsy and irony into the proceedings. Each artist contributes to Anderson’s precise and familiar themes and cinematic signatures, making the film an easy and instant addition to the filmmaker’s impressive oeuvre.

Some critics and outspoken cinephiles have argued recently that Wes Anderson hasn’t grown as a filmmaker, that in technical and narrative terms, he’s been making the same film over and over—visually idiosyncratic stories about people struggling with adolescence. Consider instead that Anderson found his distinctive voice in comedy sooner than most other directors do. Some filmmakers labor over early career missteps and make mid-career detours into oddity, but from the start, Anderson’s voice has been a matchless and unwavering presence thanks to his measured and confident skills behind the camera. He belongs on a short list of comedy directors like Ernst Lubitsch (Trouble in Paradise) and Preston Sturges (Sullivan’s Travels), who, throughout their careers, continued to make a particular kind of film defined, simply, by their name alone. Imitators may come and go, but these directors are the true originals. Anderson too. One hopes he never feels he should put aside his established style, as moviegoing would be a much less interesting place without more films like Moonrise Kingdom.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review