Reader's Choice

Monsoon Wedding

By Brian Eggert |

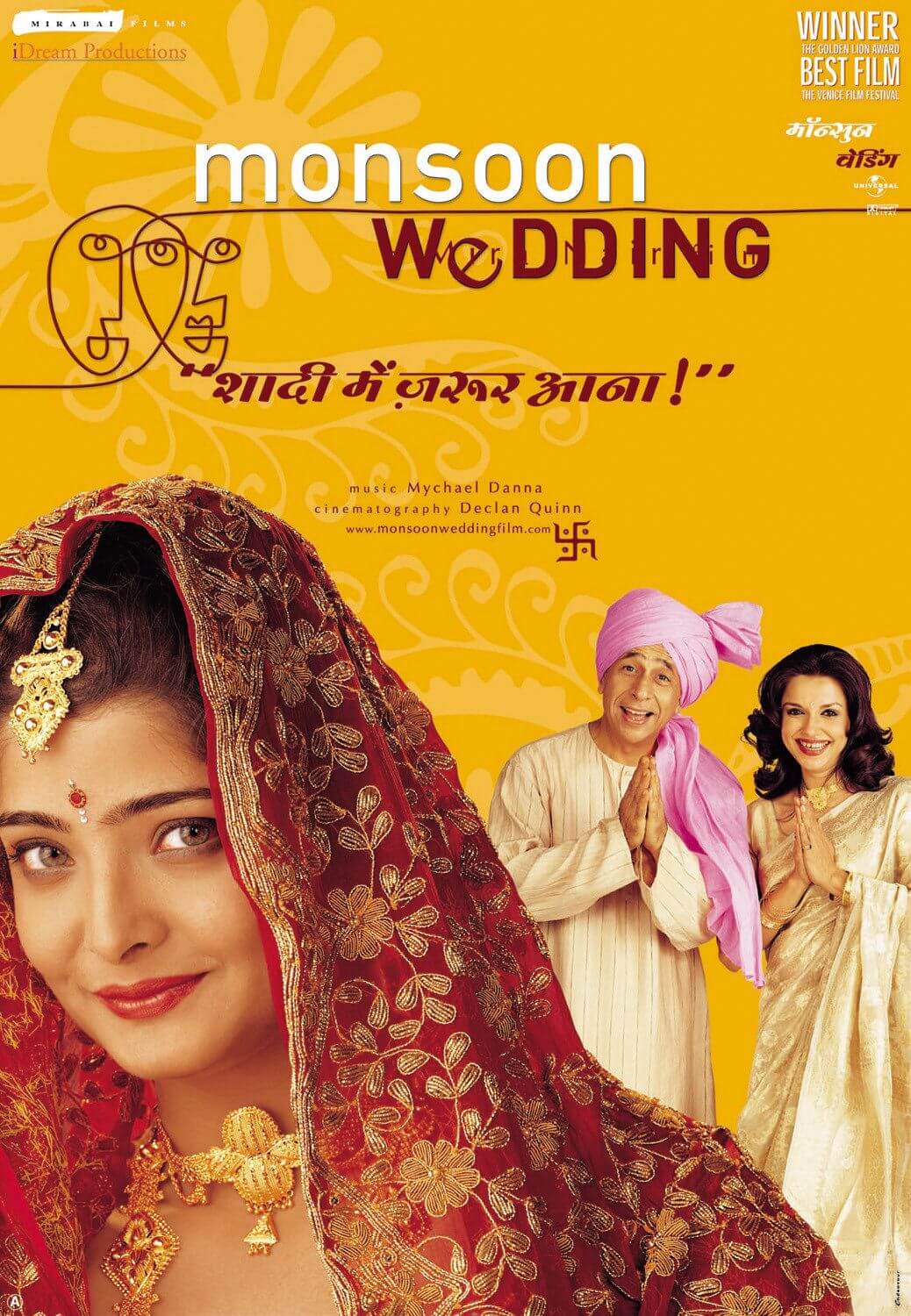

Mira Nair’s Monsoon Wedding is about everything. Part romantic comedy, part social realism, part Bollywood musical, it explores a large canvas, a multitude of characters, and a wide variety of filmmaking styles. It opens like a farce set amid the preparations of an upcoming arranged marriage. Several families will gather to partake in four days of traditional ceremonies and celebrations. Lalit Verma (Naseeruddin Shah), the paterfamilias in charge of organizing the event for his daughter, rushes the unhurried Dubey (Vijay Raaz), the wedding planner, who must rebuild a marigold arch. Dubey orders his three colleagues to get to work, while he eats the marigolds and dreamily falls for Alice (Tillotama Shome), the Vermas’ servant. At the same time, Lalit’s betrothed daughter, Aditi (Vasundhara Das), has been carrying on in an affair with her smug boss, a talk-show host, threatening to derail the family’s best-laid plans for her nuptials. Over the next two hours, Nair maneuvers from one melodramatic dilemma to another, tackles the social stratification of India’s caste system, inserts effervescent dance numbers, floors her audience with a subplot about pedophilia, and wraps everything up with a delightfully romantic ending. Just process all of that for a moment.

The world of the story takes place in New Delhi in a middle-class home, where a sprawling array of characters represent multiple languages and ethnicities. The characters speak in a blend of several languages (Hindi, English, and Punjabi), while the marriage event features guests from Australia, Muscat, the United States, and elsewhere. In some ways, it’s an upstairs-downstairs dramedy, where the romantic situations of the bourgeoisie mirror those of the servant class. The characters negotiate the intersection of traditional values and Western influence, such as the bridegroom, Hemant (Parvin Dabas), who works with computers in Houston but nonetheless agrees to an arranged marriage. The Verma family lives in a home surrounded by an urban landscape, television shows debate the Americanization of India, and everyone dresses in contemporary Western middle-class garb. Meanwhile, in the evening, time-honored ceremonies require traditional dress, such as a Mehndi party—a bridal shower where women gather to paint the bride with henna tattoos, talk about past romances, sing songs, and dance.

Monsoon Wedding is aptly titled. Though it’s set during the rainy season, it’s also a downpour of emotional situations and stylistic types. This convergence of various conventions and odd juxtapositions bears some resemblance to a traditional product of Bollywood, where random interjections and breaks in tone are customary, if not expected. Bollywood films often have a sense of heightened stimulation through a multitude of plots, colorful asides, random music numbers, and shifts in emotion, making every scene something new and unexpected, and thus infectiously watchable. Then again, Monsoon Wedding also deserves comparisons to Western wedding tapestries, such as Robert Altman’s A Wedding (1978) or Jonathan Demme’s Rachel Getting Married (2007)—or even the extended opening sequences of The Godfather (1972) or The Deer Hunter (1978). The sheer number of characters and events going on over the film’s four days of festivities allows Nair to examine every character within the expansive drama, giving them dimension through her empathetic observations. Her approach is such that, despite the evident influence of Bollywood, she ushers the material along with a social consciousness that feels removed from conventional Indian cinema.

Nair’s roots belong to the documentary. After studying acting and filmmaking at Harvard, she made documentary shorts about social issues affecting modern-day India: she addressed the stigmatized profession of erotic dancing in India Cabaret (1985), which exposed the double standard of seemingly respectable men who attend a striptease show but later demean the women performers; she also made Children of a Desired Sex (1987), about the practice of aborting female fetuses in favor of a male child. Her debut feature, Salaam Bombay! (1988), charted the lives of underprivileged children on the streets of Bombay, earning her an Academy Award nomination for Best Foreign Language Film. She continued to inject a streak of realism into her subject matter with Mississippi Masala (1991), which begins with Uganda’s anti-Asian policy that forces several Ugandan Indians to relocate in Greenwood, Mississippi. Though she has made several other films, Monsoon Wedding remains her most celebrated work. When it debuted at the Venice Film Festival in 2001, she became the first female filmmaker to win the Golden Lion Award.

Nair called the film “a Bollywood movie, on my own terms.” Her style of filmmaking can be situated somewhere in-between the social realism of Satyajit Ray and the flights of fancy explored in Bollywood. But Monsoon Wedding isn’t a film composed of the randomness and fragmentation of typical Bollywood productions; when she makes use of music and dancing, they exist within the diegesis. The song performed at the Mehndi party is observed with the camera as a participant, as opposed to breaking the narrative progression with a musical interlude. Likewise, the wedding dance performed by the cousin Ayesha (Neha Dubey) occurs naturally within the drama—it’s discussed earlier in the proceedings and built up in the plot. Other Bollywood characteristics, such as its tendency for sensory overload through a full array of colors, personalities, and a vast mosaic of characters, have been administered with a touch of naturalism, as weddings are, at their essence, multicultural and overstimulated affairs. Nair’s cinematographer Declan Quinn uses a predominantly handheld 16mm camera, observing the unfolding situation with fly-on-the-wall realism. And periodically in the film, Nair uses a transitional device in which she cuts away to the world outside of the wedding drama to the streets of Dehli, where the less privileged scrape to get by and endure the monsoon season without umbrellas or the multicolored, waterproofed canopy in the Verma’s backyard.

Many Hindi films have similar plotlines, where various characters feel lost or in conflict and, through the trappings of the story, discover what’s important to them by the end. In Monsoon Wedding, lives seem to unravel before us only to magically congeal in an uplifting way. Lalit follows the cultural precedent that requires his family’s outward integrity to be maintained at all costs, which leaves him scrambling to ensure his home has been decorated according to specifications and his family behaves accordingly, even if he goes broke in the process. It’s a mandate that occasionally brings out his cruelty, as he spurns his teenage son Varun (Ishan Nair), a boy who would prefer to dance, watch cooking shows, and attend culinary school rather than become the hardened, respectable male of traditional Hindi culture. It’s a conflict that tests Pimmi (Lillete Dubey), Lalit’s wife, who asks her husband, “What’s wrong with you?” in an aching scene. In nearly every subplot of Monsoon Wedding, and there are many, the characters work out the influences of the East and West in their lives, though they never quite find a balance.

Even though her characters never settle on a harmony between the traditional and the modern, Nair nonetheless provides endearingly dramatic resolutions. Aditi initially flounders in her commitment to the traditional wedding, preferring instead her secret (and decidedly Western-loving) inamorato. But before the end, she comes to realize the callousness of her lover and the integrity of Hemant. The most endearing love story involves Dubey, who must convince the demure Alice that his affections are genuine after his employees spy her trying on some of Pimmi’s jewelry and assume she’s a thief. Where the film shifts into unexpected seriousness is a plotline involving Lalit’s wealthy brother-in-law, Tej Puri (Rajat Kapoor), who has helped maintain the Verma family’s financial stability for years. However, Aditi’s cousin, the aspiring writer Ria (Shefali Shah), who is ostensibly a sibling after Lalit and Pimmi adopted her into the family when her father died, watches Tej with wariness as he looms over a prepubescent cousin. She reveals that Tej molested her as a child, leaving Lalit to decide whether he should honor his family’s benefactor and maintain the all-important veneer, or if he should break with tradition to renounce the sexual predator.

Though the interceding drama around Ria, beautifully performed by Shah, nearly overtakes the dramatic thrust of Monsoon Wedding in the end, making the actual wedding seem trivial, the experience overall resolves itself in Nair’s commitment to elaborately ornamented storytelling. But Nair breaks with the conventional three-hour Bollywood runtimes by enforcing a kind of narrative economy, supported by her stylistic realism that compels a certain dramatic shorthand yet never fleeces her characters. Amid the dancing and joyous festivities, she has crafted a variegated ensemble of characters. We care about them, as they live full and complicated lives. Just as the decorative bright orange marigolds stand out against the drab colors of Dehli’s weathered structures and tricky social conditions, the film’s struggles between the East and West, younger and older generations, and upper and lower classes give way to the pure sensation and pleasure of it all. It’s a celebration of life that acknowledges how family leads to both great love and anguish, yet out of that comes a willingness to endure and overcome.

(Editor’s Note: This review was commissioned on Patreon. Thank you for your suggestion and support, Elizabeth!)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review