Mongol

By Brian Eggert |

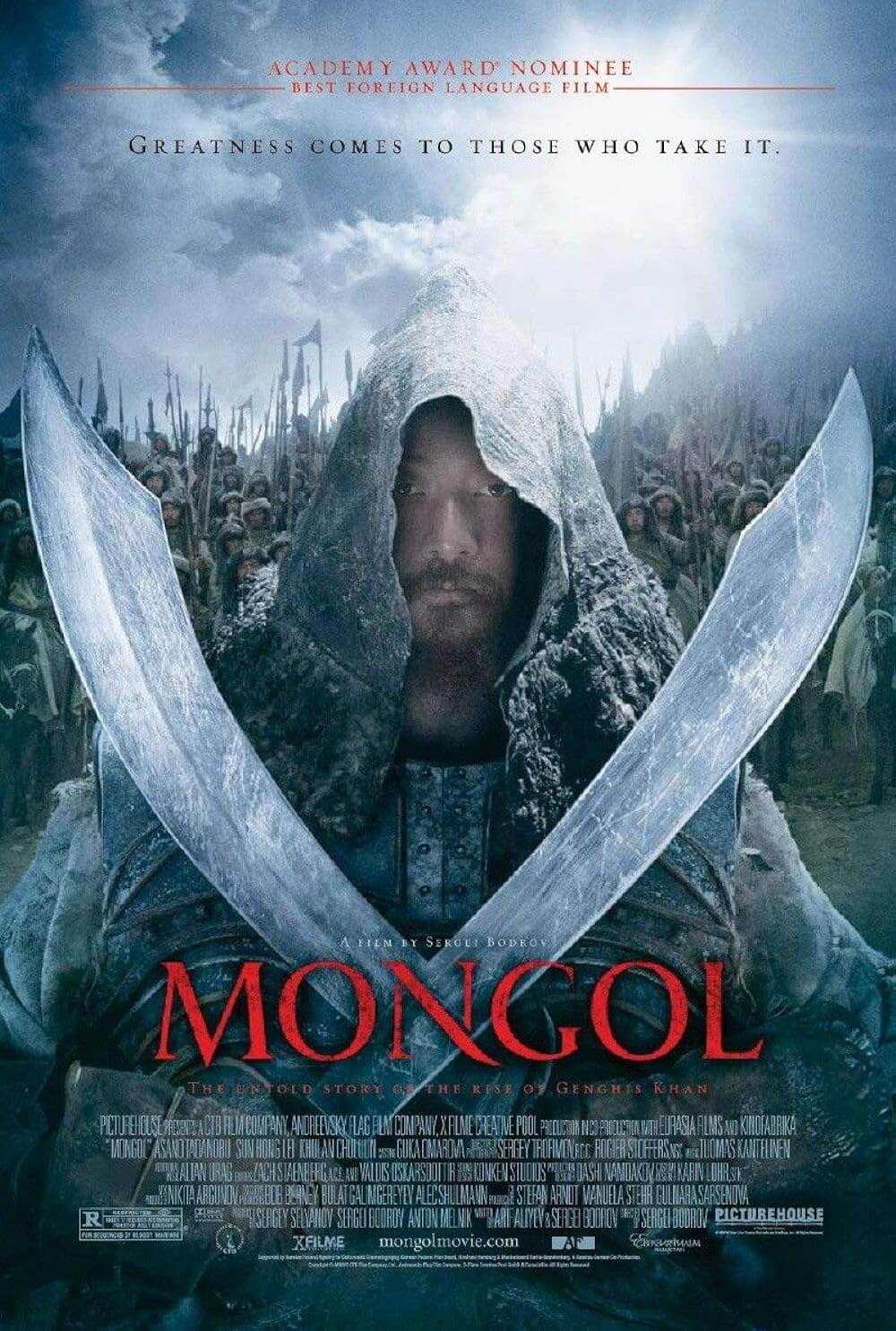

Russian filmmaker Sergei Bodrov’s proposed trilogy of films about Genghis Khan begins with Mongol, an ambitious effort made in the convention of grandiose classics by David Lean. This comparison is apt, because like Lean’s pictures (Lawrence of Arabia, The Bridge on the River Kwai), Bodrov instills humanity into his characters while appreciating the splendor of their story, setting, and dramatically-infused historicity. No event or battle is ever more important than how it relates to the central protagonist. In today’s market of excessive and emotionless epics, sporting violence for violence’s sake (see 300), a film like Bodrov’s is refreshing.

The story opens with young Temudjin, played by Odnyam Odsuren, who has a noble and wise face even at the age of nine. His father (Ba Sen) intends to take him to the Merkit tribe to settle a score, by allowing the boy to choose a future wife from their girls. Instead, Temudjin selects a strong-legged girl named Börte, not of the Merkit tribe but a weaker clan he and his father meet along the way. Being his clan’s khan, or leader, Temudjin’s father agrees to the marriage and leaves the Merkit conflict unresolved (they show up later, to be sure). Before digging too deeply into the film’s plot, first understand that twelfth-century Mongols avoided written history, passing along their tales in the oral tradition. Much of Bordov’s screenplay, or any illumination of Genghis Khan’s life, will thus be rife with inaccuracy (not that we have a frame of reference to show that it’s not truthful). And so, of course, there are gaps in the child’s progression, filled with an appropriate mysticism staging Temudjin’s eventual reign as a forgone conclusion, commanded by the Mongolian god Tengri.

At one point, the boy is captured by an opposing clan, to be held until adulthood, when he will be slain (Mongols in the film say they will not kill children). The boy escapes, his shackles apparently released by Tengri. These incidents just occur, without flashy computer-generated renderings of the god, and draw little attention to the miraculousness of their happening. Another incident involves Temudjin falling through the ice into a deep lake. How does he survive? Tengri, no doubt. But Bodrov doesn’t show us the boy magically lifted out of the water, or in the former example his chains being undone. Their suggestion implies his predestined fate.

Temudjin (the adult version played by Tadanobu Asano) slowly gathers friends by his generous and sympathetic treatment of his servants and warriors. His love for his wife (the adult version played by Khulan Chuluun) is everlasting. When she is kidnapped and bears the child of an enemy, he does not toss her or the child away; rather, he treats his wife with undying love and the child like his own. How many despotic rulers have been so understanding? Indeed, this story doesn’t even reference the name Genghis Khan until the film’s last moments and follows none of Temudjin’s later exploits conquering most of the then-known world. Perhaps this first entry is meant to humanize a man who, in the two sequels (should they be filmed; Bodrov has not yet confirmed they will be made), will become corrupt and tyrannical.

Recalling the best sort of old-fashioned storytelling wherein the heroic leader might not display the most kindly ways of achieving his ends—Temudjin explains, “Mongols need laws. I will make them obey. Even if I have to kill half of them”—but remains sympathetic nonetheless. Brodrov’s engaging saga ensues through a series of blood-splattering clashes shot with clarity and style (particularly on Blu-ray), interspersed between surprisingly affecting dramatic notes. Notice how simply Bodrov arranges the story. Though this could be construed as a negative mark, in today’s cinema, making a universal international film is rare, and welcomed, reminding one of the days when Kurosawa and Berman were involving the world in their work. If Bodrov goes ahead with his planned trilogy, he’ll have involved all of us on an impressive scope.

Mongol redeems sweeping epics filled with armies engaging in bloody swordplay, volleys of arrows, and slow-motion combat, even while embracing all their formulaic elements, by simply getting it right. After disappointments like those of Alexander and Troy, Hollywood has thought twice before investing big money in such productions. But they could learn a thing or two from Bodrov, who imbues gravitas onto Genghis Khan’s noble quest to unite his people under universal law. Whether or not he’ll maintain focus on his character’s psychology in his upcoming sequels, when Khan becomes the ruthless and savage ruler history remembers him as, remains to be seen.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review