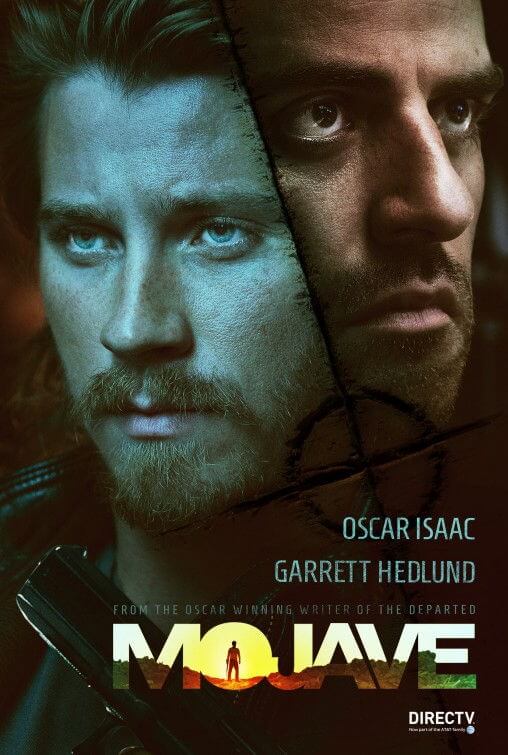

Mojave

By Brian Eggert |

Mojave is writer-director William Monahan trying to channel Norman Mailer. But just like Mailer’s sense of John Wayne machismo, this film has an artificial quality to the proceeding that hinders its attempts at thrills or self-referential humor. Screenwriter of exceptional works like The Departed and Kingdom Of Heaven, Monahan’s efforts lately have been over-written and showy. Consider his remake The Gambler, which tries to put forth Mark Wahlberg as a Harvard-educated college literature professor; Monahan writes a protagonist painfully unsympathetic, filled with selfishness and pretensions. A not dissimilar character resides at the center of Mojave, Monahan’s second turn as director after the disappointing London Boulevard.

Garrett Hedlund stars as Thomas, a writer-director not unlike Jim Morrison, had The Doors’ frontman become a filmmaker instead of a musician. With long, greasy blonde hair, a thin beard, and always a cigarette or drink nearby, Thomas is one of those maligned geniuses discontent with everything around him, despite all the privileges afforded to a Hollywood success (great real estate, a French actress/mistress, a wife and child, and so on). He heads out to the desert alone to figure things out, or perhaps kill himself because, you know, he’s such a genius. While out there, a stranger approaches his camp. Oscar Isaac plays Jack, an armed transient and probable serial killer who waxes intellectual and posits himself as the devil. Thomas sees through Jack’s literate psychobabble, steals his rifle, knocks him out cold, and leaves him for dead.

Things take a turn when Thomas sleeps in a cave and is startled awake by a ranger, whom he kills thinking it’s Jack; then he hides the evidence, only to have Jack witness everything and follow him home. Already Monahan stretches the audience’s disbelief by setting his picture in a place that could only exist in the mind of a writer—a place where two men meet at random in the desert and talk about their internal philosophies. Once the action moves back to Los Angeles, the picture becomes even more off-kilter as a borderline satire of Hollywood. Thomas is in the middle of production on a movie. Mark Wahlberg, who always appears in bathrobes, plays his producer. This is the type of character who hires two prostitutes and then orders them Chinese takeout because he has important phone calls to make. (Is that a “type”? Who can say.) Walton Goggins also appears as Thomas’ lawyer, an eerily calm specimen always shown sitting and drinking.

The eventual tête-à-tête between these two foes, Jack and Thomas, remains interesting and aggravating at the same time. Both of them make silly proclamations to justify their own dissatisfaction with the world. Thomas loves to remind people that “I’ve been famous since I was eighteen,” while Jack tells Thomas about his neglected childhood and how “I could read when I was two, brother.” That’s another thing—Jack ends almost every sentence in “brother” in his indiscernible growl-of-an-accent, a habit Thomas picks up seemingly to play along in Jack’s game. Despite being the villain, however, the ever-talented Isaac has charm that far outshines Hedlund, who’s never really clicked in any role from TRON: Legacy to Pan. In a way, we root for Jack to put the annoyingly macho Thomas out of his misery already.

Through pompous references to male writers (Byron, Mailer, Rimbaud, Shakespeare, Shaw, etc.) and dialogue that only a screenwriter could endorse (“I unconditionally accept service as your intention.”), Mojave‘s fine acting and interesting locales are wasted on irredeemable characters. They’re not even the type of awful people that remain captivating despite their flaws. The production of Monahan’s movie-within-a-movie suggests its audience will have trouble identifying with an unhappy rich man, but it’s more likely that they’ll have difficultly finding a sole redeeming quality in the central winy, scruffy artist cliché. Monahan’s basic setup has possibility, but his film falls short by failing to generate any empathy whatsoever in his potentially stirring cat-and-mouse thriller.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review