Moana

By Brian Eggert |

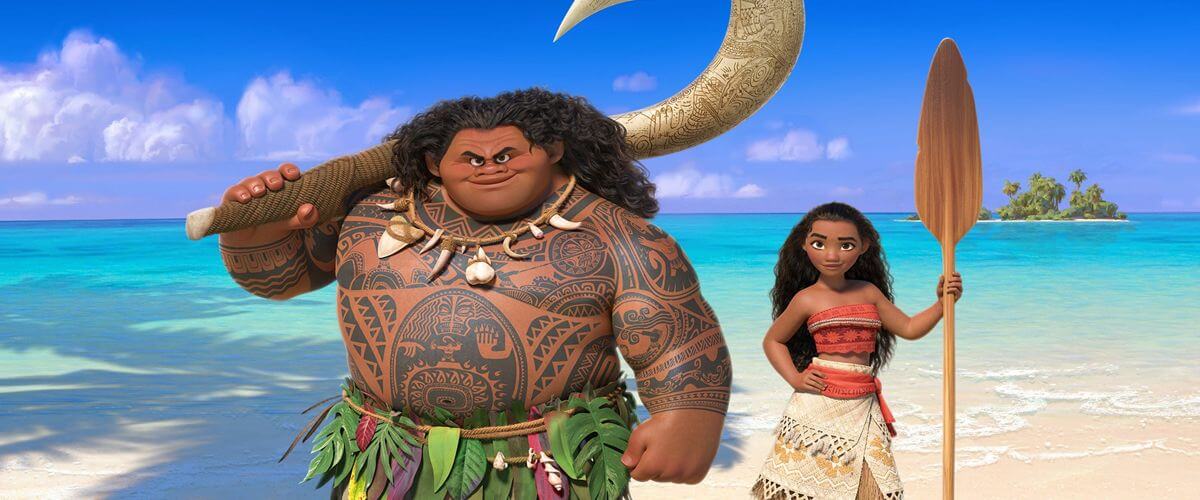

“If you wear a dress and have an animal sidekick, you’re a princess,” says Maui, a self-obsessed demigod. In her Polynesian village, Moana serves as the chief’s daughter, not royalty; nevertheless, she bears all the traits of your typical Disney princess. Alongside her dim pet rooster, Heihei, a comic relief character even more useless than the talking snowman in Frozen, Moana sets out on an adventure of self-discovery against her father’s wishes. Following this boilerplate scenario, the heroine of Walt Disney’s animated musical Moana remains a princess regardless of her title. Directors John Musker and Ron Clements established this formula in 1989 with The Little Mermaid, and then followed their model in Aladdin (1992) and The Princess and the Frog (2009, underrated). Musker and Clements are joined by co-directors Chris Williams and Don Hall here, and despite the absurd volume of directors behind the production, Moana is an entertaining and often beautiful entry into the Disney canon.

When she realizes her island village is slowly dying, Moana (voice of Hawaiian newcomer Auli’i Cravalho) defies her overprotective father and sets out to find Maui (Dwayne Johnson). According to Polynesian legend, Maui stole the heart of Te Fiti, the goddess of life, a thousand years ago—the “heart” being a small, glowing green stone. But the heroic Maui has since lost the stone and his magical fish hook beneath the sea, the latter of which allows him to shape-shift into various animals. Life will flourish again once the heart is returned to Te Fiti, who lies beyond a wall protected by the volcanic deity Te Ka. But before that can happen, Moana must convince the egomaniacal Maui to cooperate. Serving as a kind of scatterbrained version of the Genie from Aladdin, Maui reluctantly guides Moana on a quest to recover his fish hook and return Te Fiti’s heart.

Aside from its plot originating from actual Polynesian mythologies, Moana’s characters adopt many of its idiosyncrasies and personality from Samoan and other South Pacific cultures. Maui and the proud men from Moana’s island appear covered in decorative tattoos, their bodies shaped like puffed-up figurines made of fondant, rather than the doll-like appearance of the princesses from Frozen. Their long, wavy, dark brown hair moves in fascinating ways (bringing to mind Princess Merida’s transfixing locks in Pixar’s Brave) as they perform traditional Polynesian dances. Best of all, the story’s wildest and most outlandish quirks come from the joyful legends passed among Polynesian people. The film’s immersion into these cultures remains something different than U.S. audiences are accustomed to seeing, which seems more important in our culture today than ever before.

However unique its cultural signifiers may be, Moana has a number of scripting issues. Somehow, Jared Bush’s screenplay (based on a story credited to seven other writers) manages to make a Twitter reference and lots of awwwkward-type humor, which attempts to put modern personality types in a mythic setting. Bush also incorporates more than just a chicken sidekick; there’s also Moana’s pet pig, who, much like most non-human characters in the film, communicates through quizzical head tilts. And then there’s Johnson’s off-screen personality that bleeds into his Maui performance—specifically, the former wrestler’s signature eyebrow raise, an attribute as tired as Arnold Schwarzenegger working “I’ll be back” into every conversation. Each of these details seems out of place for an outside-of-time legend, removing the viewer from the experience, albeit momentarily.

However unique its cultural signifiers may be, Moana has a number of scripting issues. Somehow, Jared Bush’s screenplay (based on a story credited to seven other writers) manages to make a Twitter reference and lots of awwwkward-type humor, which attempts to put modern personality types in a mythic setting. Bush also incorporates more than just a chicken sidekick; there’s also Moana’s pet pig, who, much like most non-human characters in the film, communicates through quizzical head tilts. And then there’s Johnson’s off-screen personality that bleeds into his Maui performance—specifically, the former wrestler’s signature eyebrow raise, an attribute as tired as Arnold Schwarzenegger working “I’ll be back” into every conversation. Each of these details seems out of place for an outside-of-time legend, removing the viewer from the experience, albeit momentarily.

Fortunately, the gorgeous animation compensates for an occasionally predictable and hammy script. Viewers may find themselves getting swept up in the photo-real water, the lifelike movement of hair (particularly that of Moana and Maui), or the detail of a scene where Moana finds herself covered in sand. Elsewhere, the bioluminescent undersea life forms and bright oceanic backgrounds pop on the screen in vivid colors. For one sequence during the hilarious song “You’re Welcome,” written by Hamilton creator Lin-Manuel Miranda, the foreground animation looks even more lifelike when the background turns into a flat plane, recalling musical numbers from the 1960s. Another sequence, an actionized chase, seems to pay homage to Mad Max: Fury Road with a caravan of Kakamora pounding wild drums in spiky coconut costumes. The inventiveness of such asides easily compensates for typical “I want” songs and other required moments in a model Disney film.

Alongside Miranda, Opetaia Foa’I (lead singer of the band Te Vaka) and Disney collaborator Mark Mancina create several memorable songs that adopt the style of South Pacific cultures. Although I may be in the minority for thinking Frozen’s “Let It Go” was grossly overrated, Moana’s soundtrack embeds several songs and melodies in the viewer’s brain. The aforementioned “I want” song called “How Far I’ll Go” may be one of the best of its kind, whereas the village’s journey tune “We Know the Way,” performed in the Tokelauan language, rings with authentic harmonies that hit the viewer in the chest. Perhaps the most entertaining of the film’s songs is “Shiny,” performed by Flight of the Conchords’ Jemaine Clement, who lends the giant crab monster Tamatoa his smooth, deep voice and oddball humor.

Moana’s dependence on its familiar structure may reduce it to an average experience overall, but the film’s few innovations are inspired. For instance, Moana’s gender never becomes an issue. She doesn’t define herself or her quest through a prince, and in fact, the film never develops a romance subplot at all. Having a resourceful and independent heroine at the center of a story about demigods and larger-than-life monsters shows Disney’s willingness to modernize (somewhat, anyway). Likewise, the film’s immersion into a specific culture’s belief systems demonstrates their desire to take occasional risks, although not to the socially reflective extremes of their other 2016 film, Zootopia. Most of all, Moana proves so visually stunning that all other qualities recede, and the audience beams afterward in awe of its sheer beauty.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review