Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation

By Brian Eggert |

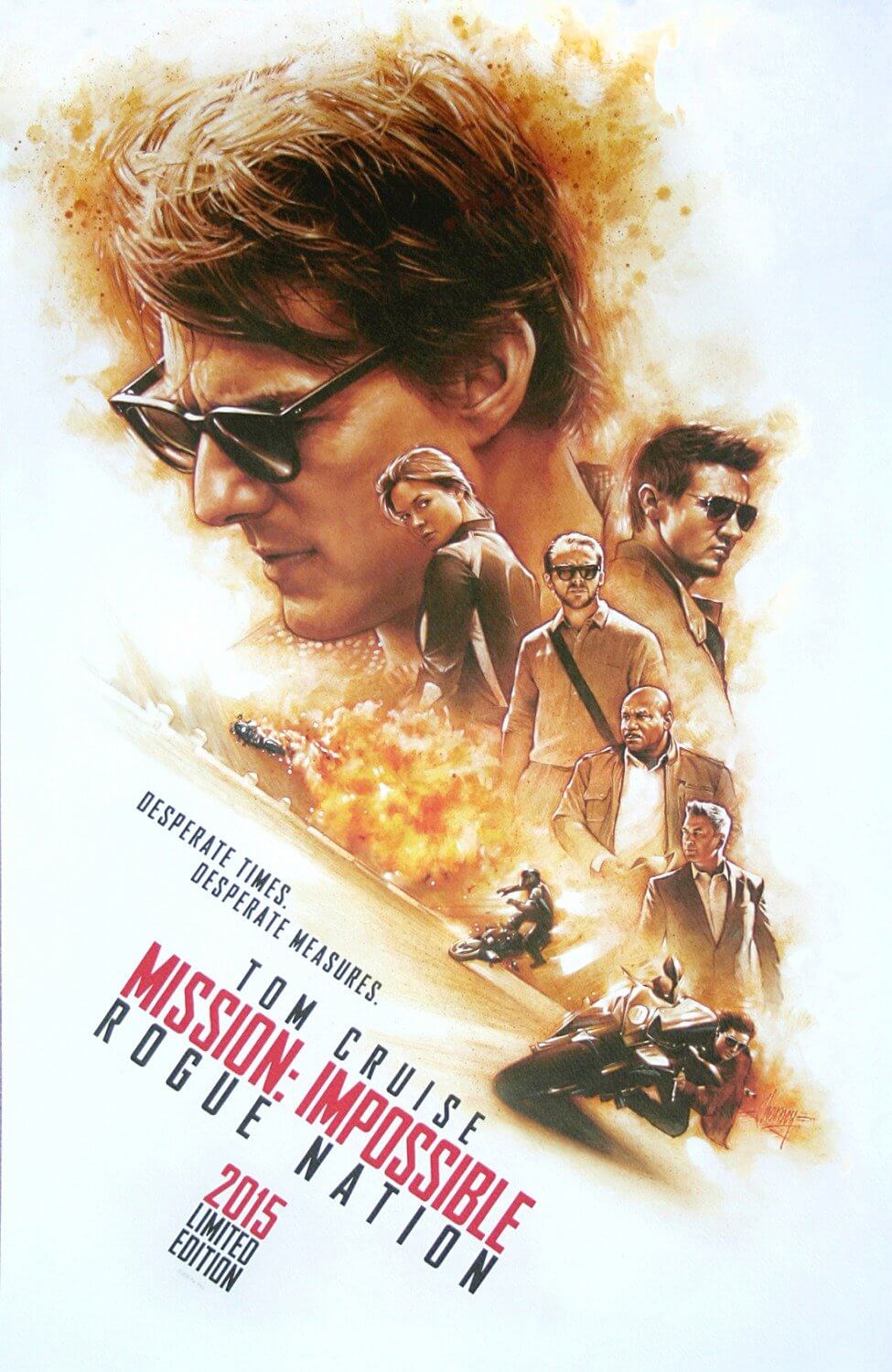

In one of many breathless sequences offered by Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation, Tom Cruise’s durable IMF hero Ethan Hunt scurries around backstage in the Vienna Opera House, as a lavish production of Turandot ensnares its audience. Though he’s there to locate a terrorist leader, Hunt finds not one, not two, but three assassins with weapons trained on an international dignitary. Drawing inspiration from a sequence in Alfred Hitchcock’s The Man Who Knew Too Much (Jimmy Stewart, not Peter Lorre), the hero negotiates the situation in silence, the opera drowning out virtually all diegetic sound. He tracks one of the assassins backstage and into the rigging, where platforms raise and lower, proving to be dangerous ground for a fight. Meanwhile, the opera carries on, the sounds of hard-delivered punches and silencer gunfire muted by the crescendos of performers and the orchestra. Working from a story he conceived with Drew Pearce, writer-director Christopher McQuarrie evokes Hitchcock with this brilliant sequence, but also Brian De Palma, director of the first Mission: Impossible from 1996.

By the time most franchises reach their fifth installment, if they ever get that far, they become stale, predictable, and tiresome. But following four entries and most of them solid, Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation boasts a screenplay with several genuine surprises, virtuoso sequences, and thrills to spare. Even better, it’s easily the smartest entry since De Palma’s original. Indeed, McQuarrie, who has collaborated with Cruise on four previous occasions (including screenplays for Valkyrie and Edge of Tomorrow) and made his directorial debut on the Cruise starrer Jack Reacher, takes inspiration from De Palma on a number of occasions. Most significantly, McQuarrie follows the mold of the original in that, aside from a few moments of purely actionized screentime, Rogue Nation inhabits the realm of a slick spy-thriller—more about elaborate schemes and incredibly well-executed plans than mindless action. But then, even the action in Rogue Nation serves a purpose to the story and arrives in tense beats.

Take the opening’s James Bond-like appetizer, which finds Hunt and his techie sidekicks, Benji Dunn (Simon Pegg) and Luther Stickell (Ving Rhames), answering to analyst William Brandt (Jeremy Renner) during a mission to recover biological weapons in Minsk. The setup ends with Hunt hanging on the side of an airplane during takeoff, until Benji can calm his hysterics to open an exterior door remotely. It’s a wowing piece of cinema because McQuarrie takes advantage of Cruise’s willingness to perform his own stunts. But it’s not Cruise’s bravado physicality that carries the whole of Rogue Nation; it’s the involved plotting. The biological weapons were one component of a larger terrorist organization called The Syndicate, an “anti-IMF” comprised of thought-dead intelligence agents from around the globe. Early on, a mysterious bespectacled figure (Sean Harris, creepy) from The Syndicate gasses and captures Hunt, dooming him to torture by a goon nicknamed “The Bone Doctor” (Jens Hulten). But while trapped, he’s assisted in his escape by Ilsa Faust (Rebecca Ferguson), a double- or possibly triple-agent whom Hunt isn’t sure whether to kiss or kill.

Take the opening’s James Bond-like appetizer, which finds Hunt and his techie sidekicks, Benji Dunn (Simon Pegg) and Luther Stickell (Ving Rhames), answering to analyst William Brandt (Jeremy Renner) during a mission to recover biological weapons in Minsk. The setup ends with Hunt hanging on the side of an airplane during takeoff, until Benji can calm his hysterics to open an exterior door remotely. It’s a wowing piece of cinema because McQuarrie takes advantage of Cruise’s willingness to perform his own stunts. But it’s not Cruise’s bravado physicality that carries the whole of Rogue Nation; it’s the involved plotting. The biological weapons were one component of a larger terrorist organization called The Syndicate, an “anti-IMF” comprised of thought-dead intelligence agents from around the globe. Early on, a mysterious bespectacled figure (Sean Harris, creepy) from The Syndicate gasses and captures Hunt, dooming him to torture by a goon nicknamed “The Bone Doctor” (Jens Hulten). But while trapped, he’s assisted in his escape by Ilsa Faust (Rebecca Ferguson), a double- or possibly triple-agent whom Hunt isn’t sure whether to kiss or kill.

Unfortunately, The Syndicate remains so clandestine that it’s virtually a myth, and not a particularly well-received myth in Washington. There, CIA head Alan Hunley (Alec Baldwin) shuts down the IMF for their brash tactics, citing the disarmed nuclear bomb crashing into the Transamerica Pyramid at the end of Ghost Protocol as evidence of their recklessness (nevermind that the IMF disarmed said bomb). Hunley’s overarching disbelief in the IMF is aimed at Ethan Hunt, questioning if he’s just lucky for having survived no end of impossible missions, or if he’s actually in control. The more overarching conflict of Rogue Nation, then, becomes Hunt’s need to prove he has absolute control, despite The Syndicate proving at every turn that it’s outmaneuvering him. With the IMF disbanded, Hunt becomes a fugitive, evading Hunley’s attempts to bring him in while also searching for clues to The Syndicate’s organization. Of course, by the high-stakes finale, Hunley ends up convinced that Hunt isn’t an enemy of the state and even goes so far as to proclaim, “Hunt is the living manifestation of destiny”—a none-too-subtle attestation that squelches any doubt in our hero.

If there’s any significant complaint about Rogue Nation, it’s that the film’s best sequences are not equaled with the high-precision cinematography Robert Elswit brought to Ghost Protocol. Elswit’s color palate here appears gritty and muted, his framing and Eddie Hamilton’s editing more concerned with propelling the story than delivering impressive cinematics. This is not lesser cinematography, however; it is simply designed in service of the story—a choice intended by McQuarrie. Any viewer disappointment comes only from imagining how De Palma or Ghost Protocol’s director Brad Bird may have shot it differently. Take a brilliant underwater computer hack sequence that operates not only as an elaborate heist but also as an exercise in one-upmanship. It recalls the elaborate CIA Headquarters heist from De Palma’s original, and it’s literally breathless with Hunt required to be underwater for three minutes sans air tank. And then afterward, McQuarrie redeems motorcycle chases for the Mission: Impossible franchise (after John Woo put Hunt on a motorcycle for the disastrous Mission: Impossible 2 and repeated the entire martial arts-laden sequence derived from his U.S. debut Hard Target in 1993). In Rogue Nation, Cruise actually drives a speeding crotch rocket on the Marrakech motorway, with turns so sharp the actor must have skinned his knees.

Nevertheless, McQuarrie and Elswit deliver an exciting globe-trotting effort, wracking levels of tension atop one another with sequence after sequence, leaping to locales like Vienna, Morocco, Casablanca, and finally London. His more workmanlike approach allows the audience to focus on the story and characters. Because of this, we watch as Cruise reprises his longtime role and adds much humor into his very subtle, very funny looks of exhaustion. At 53, Cruise has come a long way to overcome personal and professional setbacks off-screen; and no matter how the audience may feel about him as a human being, he’s still an incredibly charismatic hero on film. (When Benji offers Hunt’s services for the three-minute underwater heist as if the task will present no problems whatsoever, Cruise’s reaction is priceless.) Pegg is also particularly good in this sequel, proving he’s much more than a comedian; Baldwin and Simon McBurney make effective intelligence bureaucrats; and Tom Hollander’s comic wryness is put to good use as the British Prime Minister. But the standout is Ferguson, who fulfills an elusive spy role.

Nevertheless, McQuarrie and Elswit deliver an exciting globe-trotting effort, wracking levels of tension atop one another with sequence after sequence, leaping to locales like Vienna, Morocco, Casablanca, and finally London. His more workmanlike approach allows the audience to focus on the story and characters. Because of this, we watch as Cruise reprises his longtime role and adds much humor into his very subtle, very funny looks of exhaustion. At 53, Cruise has come a long way to overcome personal and professional setbacks off-screen; and no matter how the audience may feel about him as a human being, he’s still an incredibly charismatic hero on film. (When Benji offers Hunt’s services for the three-minute underwater heist as if the task will present no problems whatsoever, Cruise’s reaction is priceless.) Pegg is also particularly good in this sequel, proving he’s much more than a comedian; Baldwin and Simon McBurney make effective intelligence bureaucrats; and Tom Hollander’s comic wryness is put to good use as the British Prime Minister. But the standout is Ferguson, who fulfills an elusive spy role.

Originally set for a December 2015 release, Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation moved up five months because McQuarrie wrapped shooting and cut the picture together early—that’s just how deliberate and well-executed this film is. Additionally, distributors at Paramount, along with international financiers at Alibaba Picture Group and China Movie Channel, undoubtedly wanted to avoid any close proximity to the new Bond adventure, Spectre, another spy yarn involving a clandestine terrorist organization not unlike The Syndicate. Beating Spectre to the punch, Rogue Nation will certainly prove less serious and more playful than another über-serious Daniel Craig entry in the 007 franchise—this despite Rogue Nation’s thematic drive of luck and destiny. And though time will tell which film fares better, Rogue Nation stands as another strong sequel in a rather consistent string of three: Mission: Impossible III may have the most heart, Ghost Protocol may contain the best visual presentation, but Rogue Nation stands as the best storytelling since De Palma was behind the camera and delivered the best of them all. With how engaged and well-executed this and recent entries prove to be, part six cannot come soon enough.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

As the season turns toward gratitude, I’m reminded how fortunate I am to have readers who return week after week to engage with Deep Focus Review’s independent film criticism. When in-depth writing about cinema grows rarer each year, your time and attention mean more than ever.

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your moviegoing—whether it’s context, insight, or simply a deeper appreciation of the art form—I invite you to consider supporting it. Your contributions help sustain the reviews and essays you read here, and they keep this space independent.

There are many ways to help: a one-time donation, joining DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or showing your support in other ways. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review