Mission: Impossible II

By Brian Eggert |

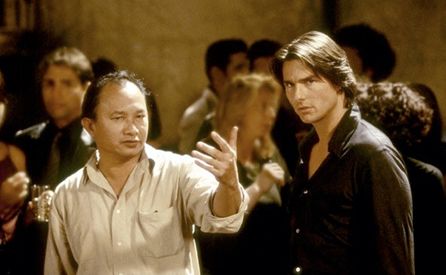

If you remove an early scene where Tom Cruise’s longhaired hero Ethan Hunt receives his “your mission, should you choose to accept it” message via sunglasses, after which he throws the will-self-destruct-in-5-seconds message at the viewer as it explodes (if only 3D were popular then), there’s almost no connecting the dim-witted Mission: Impossible II to Brian De Palma’s virtuoso predecessor from 1996, nor even the original CBS television series from the 1960s. Directed by Hong Kong action maestro John Woo, the 2000 film reduces the franchise’s spy thriller origins into a brainless action movie packed with standard Woo-isms. From overused slow-motion to random doves, from motorcycle chases to mid-air shootouts with a gun in each hand, Woo slathers on his directorial signatures, making this big-budget sequel even more confounded than its unintentionally silly, humorless, run-of-the-mill plotline alone, which is a considerable sum.

Cruise/Wagner Productions and Paramount Pictures sought a sequel strong enough to stand alone, rather than pick up precisely where De Palma’s film left off. In part, this was a reaction to a widespread belief that De Palma’s Mission: Impossible lacked personal motivations for its characters. But more significantly, it lacked action and sex—all those kiss-kiss bang-bang qualities that appeal to commercial audiences. As a result, the filmmakers resolved on a change in tone, a shift in directorial style, and a more actionized plot for their second go-round. And so, rather than try something matchless, as De Palma had done, the producers countered with mainstream overkill by hiring Woo, whose recent hits Broken Arrow (1996) and Face/Off (1997) suggested the director’s Hollywood career would be just as successful (commercially, not artistically) as his Hong Kong films. But from day one, bringing on Woo pigeonholed the production into mere “John Woo film” territory and nothing more. Naming it “Mission: Impossible” only rubbed salt in the wound of franchise fans.

Robert Towne, who contributed to the original’s story, wrote the script (although, several other writers tinkered here too) in full James Bond mode, yet with a tonal sedateness that sought to heighten the viewer’s involvement through typical devices: namely, a love interest and end-of-the-world stakes. Woo added his own contributions by elaborating on the story to allow for maximum action, including multiple car chases, latex mask reveals, and gunfights galore. Due to disagreements over the script, and reported creative clashing between Cruise and Woo, production shut down for nearly two months as the script was retooled. This became most unfortunate for Dougray Scott, playing the film’s villain. Scott was originally cast as the iconic superhero Wolverine in Bryan Singer’s X-Men (2000), which was scheduled to shoot immediately after M:I-2, as it became known. Because of the delay, Scott was forced to bow out, and Hugh Jackman took over as Wolverine. (Note: There’s probably not a day that goes by that Scott doesn’t regret signing to this movie. Instead of Jackman’s hugely successful career and several X-Men sequels, Scott has been reduced to drivel like Hitman (2007) and the second direct-to-video sequel of Death Race.)

The story opens with Ethan Hunt free climbing a Utah ridge on his vacation, and his high-effort climbing scowls will become a permanent fixture throughout the movie. Despite his best attempt to hide, his IMF superior (Anthony Hopkins, uncredited) finds Hunt and orders him to Spain, where he’s to recruit professional thief Nyah (Thandie Newton, pouting through her performance) to bed and investigate her ex-boyfriend, former IMF agent Sean Ambrose (Scott). Located in Sydney, Australia, Ambrose has arranged a scheme with a pharmaceutical company man (Brendan Gleeson, wasted on a one-note role) to unleash a deadly virus on the public, after which they’ll make the read-to-go vaccine available for purchase and earn millions. Of course, before Nyah’s seduction duties begin, she has just enough time to fall for Hunt, making the whole ordeal disagreeable for both. But if audiences took issue with (their underestimation of) Cruise’s role from Mission: Impossible, the sequel makes the original’s Ethan Hunt look multi-dimensional in comparison. Cruise’s seriousness is never once lightened by the actor’s natural energy or charm, as it had done in the first one. His orange tan does most of his acting. Worse, Cruise’s sexual chemistry with Newton is almost nonexistent. He shared more playful scenes and cleverly flirtatious dialogue with Vanessa Redgrave in De Palma’s film.

As the plot drags on, Hunt’s IMF pals Luther Stickell (Ving Rhames) and Aussie comic relief pilot “Billy Bird” (John Polson, because Steve Irwin wasn’t available) case Ambrose. A heist-like mission to destroy the deadly virus fails, and Ambrose catches on quickly to Nyah’s double-cross. To get the jump on one another and propel a number of convoluted plot “twists,” they engage in latex mask games, with Ambrose wearing a Hunt mask and vice versa to confuse the barrage of hired goons. Shootouts commence. Nyah injects herself with the virus to protect the world, giving Hunt only 20 hours to save her. A digital countdown reminds us how last-minute Hunt’s inevitable rescue will be. More shootouts. More rubber masks. Grenades are tossed. Hunt has the option of a red motorcycle or a black one—he chooses black, but only after putting on his shades and leather coat. Now he’s a biker. Then there’s some fire, and Tom Cruise rides his black motorcycle through it. In the finale, we learn the IMF apparently teaches its agents that, in a motorcycle fight, you should ride head-on against your opponent and then, when you’re close enough, jump off the bike and collide with your enemy mid-air. Hunt and Ambrose do just that. After some extended hand-to-hand combat on a beach, Hunt defeats Ambrose with a series of kicks, and Nyah is rescued only to become another in a long line of forgotten Bond girls.

Indeed, the plot borrows elements from Bond movies, specifically Goldeneye (1995), but also from Hitchcock’s Notorious (1946) and Sam Raimi’s Darkman (1990). Ambrose serves as an equivalent to Sean Bean’s former agent-gone-baddie from Goldeneye; both megalomaniacal characters make you wonder how they ever passed a psych exam in their respective top-secret agencies. There’s also an early scene where Hunt and Nyah follow a flirtatious car race with sex, another cue taken from Goldeneye. Pilfering from Notorious, the plot finds Hunt placing his lover Nyah into the enemy’s bed, just as FBI agent Cary Grant placed his lover-turned-Mata-Hari into Claude Rains’ Nazi arms in Hitchcock’s film. And for Darkman, a film about a scarred Liam Neeson generating masks to infiltrate his enemies, M:I-2 uses a scene from Raimi’s pic almost verbatim: our screaming hero enters the room, the bad guys shoot him, and then they remove his mask to reveal one of their own underneath a mask, his mouth taped shut.

Woo also borrows from his own work, everything from Hard Boiled (1992) to Hard Target (1993), but also every movie he’s made where doves flutter across the screen (which is several). What the hell do flapping doves have to do with anything, anyway? Not much, and yet they appear. Wishy-washy editing and redundant flashbacks remind us of plot points we haven’t yet forgotten, and within minutes of the movie’s start, the stale mood becomes unintentionally funny, to the degree that this film feels like a parody of Woo movies. Overall, Woo’s technique plays to the lowest common denominator. Even the soundtrack is an indication of the inferior intelligence at work. Whereas Mission: Impossible employed Danny Elfman and U2 bandmembers Larry Mullen, Jr. and Adam Clayton, the sequel goes simple and includes an electric guitar score from Hans Zimmer, with contributions from metal bands Limp Bizkit and Metallica. Between the original and this sequel, musically, it’s like comparing composer Philip Glass to the hair band Poison.

Woo also borrows from his own work, everything from Hard Boiled (1992) to Hard Target (1993), but also every movie he’s made where doves flutter across the screen (which is several). What the hell do flapping doves have to do with anything, anyway? Not much, and yet they appear. Wishy-washy editing and redundant flashbacks remind us of plot points we haven’t yet forgotten, and within minutes of the movie’s start, the stale mood becomes unintentionally funny, to the degree that this film feels like a parody of Woo movies. Overall, Woo’s technique plays to the lowest common denominator. Even the soundtrack is an indication of the inferior intelligence at work. Whereas Mission: Impossible employed Danny Elfman and U2 bandmembers Larry Mullen, Jr. and Adam Clayton, the sequel goes simple and includes an electric guitar score from Hans Zimmer, with contributions from metal bands Limp Bizkit and Metallica. Between the original and this sequel, musically, it’s like comparing composer Philip Glass to the hair band Poison.

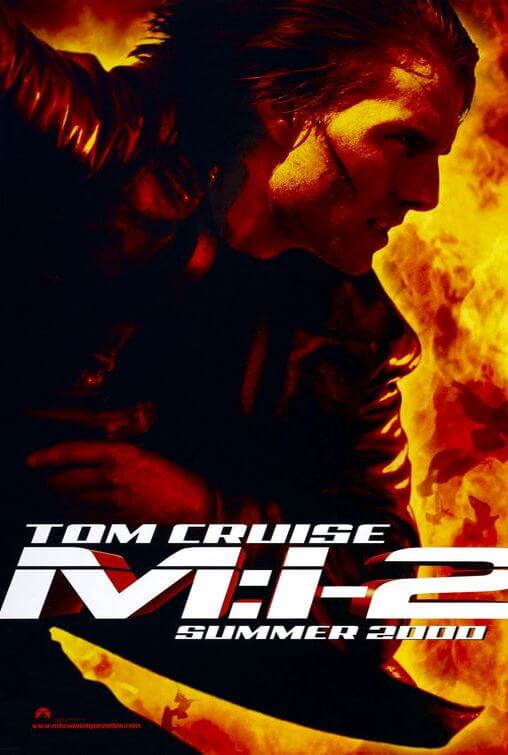

If you need further proof of this film’s dullness, look at the poster. It shows Cruise running, gun in hand, with a massive ball of fire behind him. When was the last time a fireball sold anything? As it turns out, the answer is the year 2000, with the release of M:I-2, which grossed $57 million on opening weekend and $215 million in its full North American run. At the very least, Woo’s film, even more poorly received by critics than its predecessor (but justifiably this time), grossed enough money to promise a third entry. For this franchise, it’s an uncharacteristic chapter best skipped and altogether forgotten. Woo’s self-indulgence spoils most scenes, his directorial signatures failing to blend with the material in the way that De Palma’s slick control enhanced his spy thriller scenario. And yet, every tool in De Palma’s considerable bag of tricks couldn’t make this derivative screen story worth the 123-minute runtime. Nothing about the movie works, and even less is worth remembering.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review