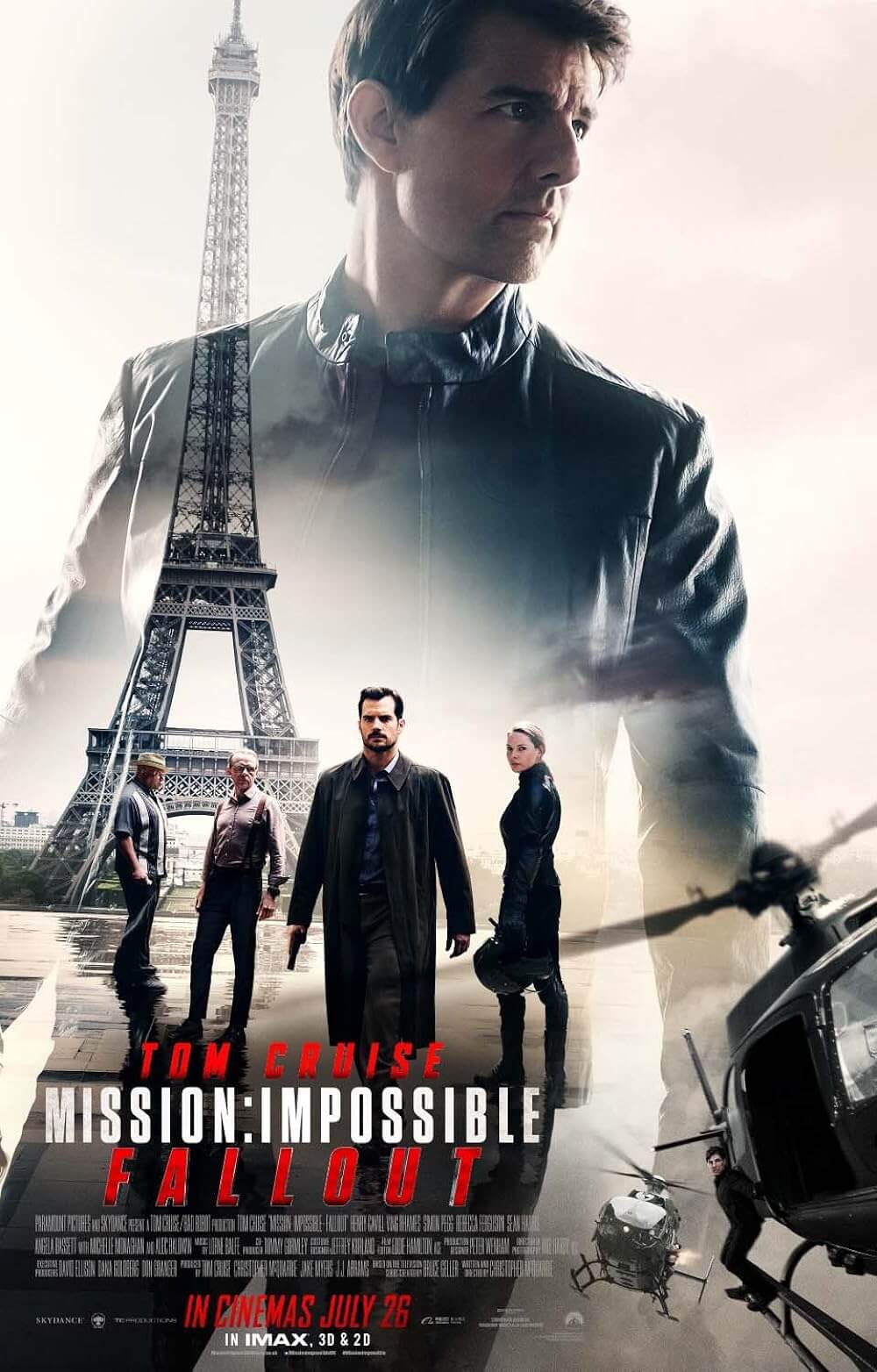

Mission: Impossible – Fallout

By Brian Eggert |

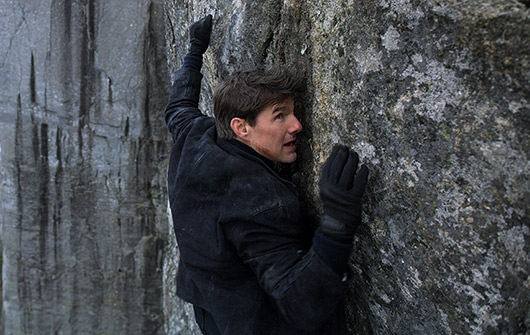

Tom Cruise is the cinema’s greatest action star. Fortunately, such a hyperbolic claim is not without an argument to back it up. Around the dawn of the last century, Douglas Fairbanks swashbuckled his way to fame by climbing walls, riding horses, and swinging from ropes in titles like The Mark of Zorro (1920) or Robin Hood (1922). Although Fairbanks was an accomplished gymnast, he eventually conceded to use stunt doubles for the most daring feats. After Fairbanks, Errol Flynn took the crown, having shot his own arrows and performed dangerous sword fights in The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) and The Sea Hawk (1940). In the subsequent decades, actors including Tyrone Power, Bruce Lee, Harrison Ford, Sylvester Stallone, Arnold Schwarzenegger, and others became action icons, but few could actually perform the exploits of their characters and instead relied on the talents of stunt workers. Perhaps because their skills are evident onscreen, martial artists have dominated cinematic bravado in recent decades, allowing for Jackie Chan and Jason Statham to impress with their ability to carry out elaborately choreographed fights. But how many of these actors, from Fairbanks to Chan, have tied themselves to the side of a plane? How many have driven at top speeds in fast-paced motorcycle races, hung from a helicopter in midair, climbed mountains without a net, outran an exploding aquarium, or held his breath underwater for several minutes? How many have dangled on the tallest building in the world?

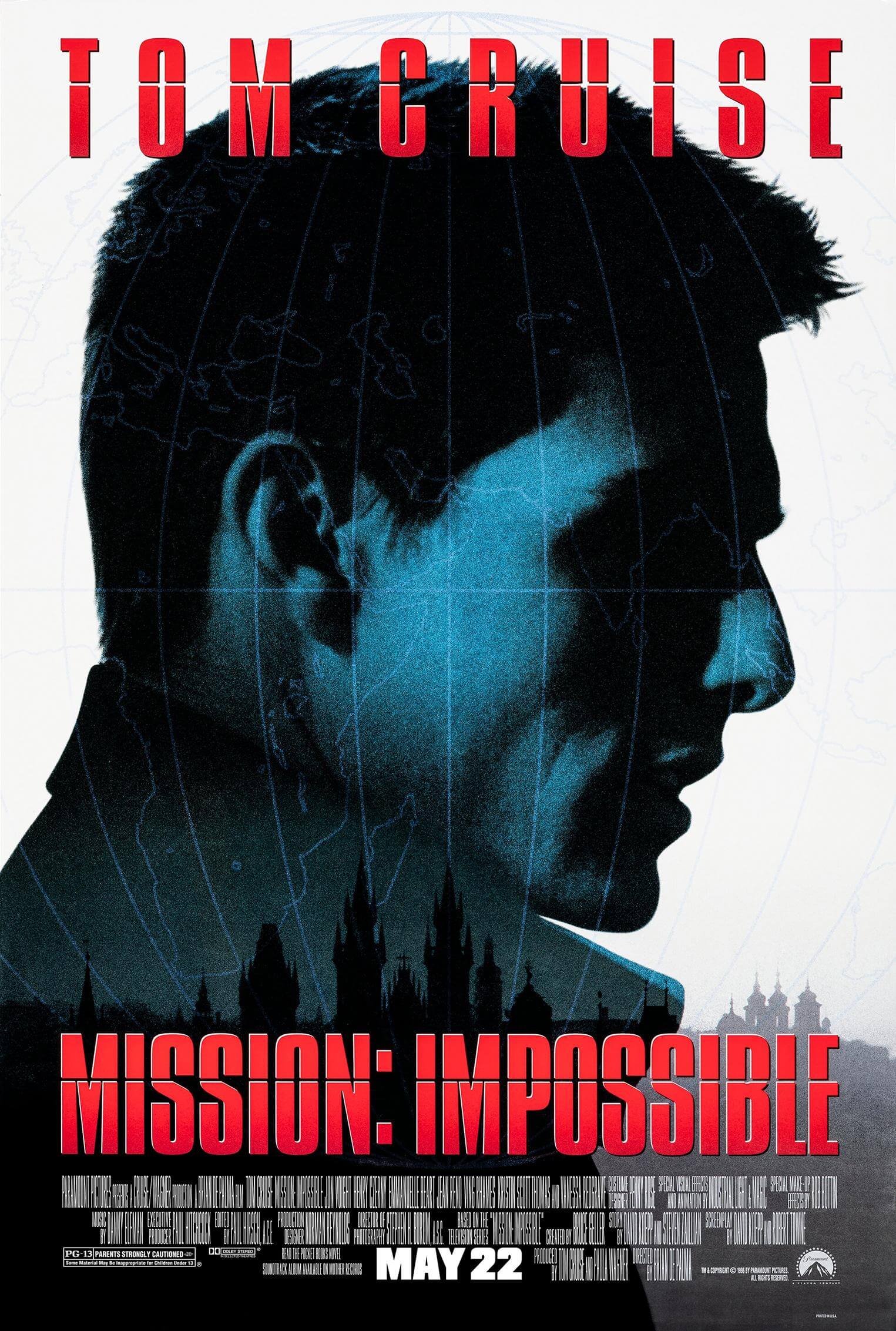

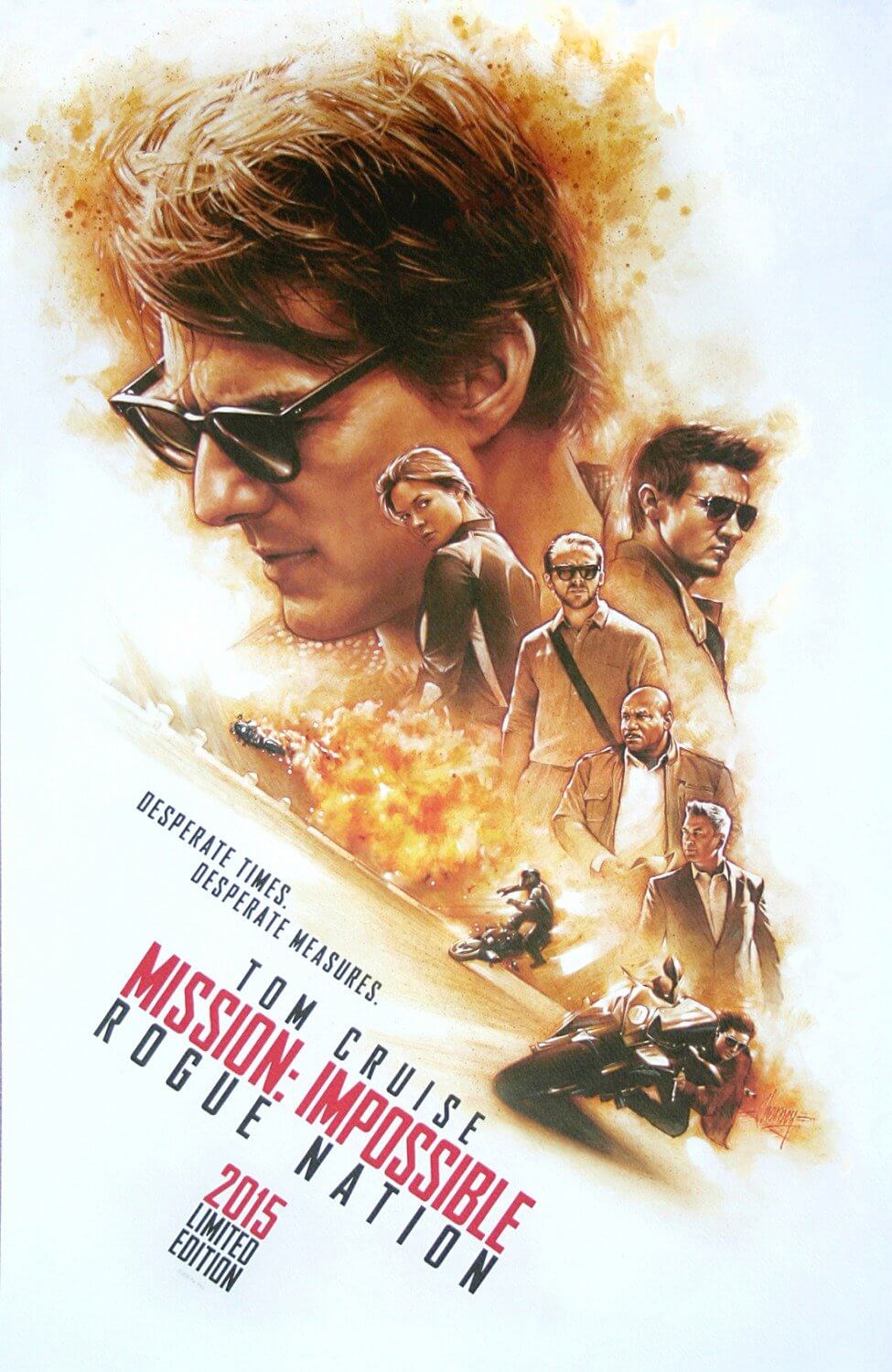

Only Cruise has subjected himself to such exploits and more for the sake of screen action, and the above-listed examples remain restricted to the Mission: Impossible franchise, still going strong since its dazzling Brian De Palma debut in 1996. The sixth entry, Mission: Impossible – Fallout, contains some series-best spectacles, among them a memorable car chase to rival the one in The French Connection (1971), brutal hand-to-hand combat, and a breathless helicopter chase—for which Cruise learned to fly helicopters and then piloted his own craft in the film. Director Christopher McQuarrie, who captained the previous entry, Rogue Nation, sells every incredible set-piece not just because he realizes the proceedings in such a clearly presented way, complete with an effortless shot-by-shot logic and visual cohesion, but because Cruise sells the most unbelievable moments in the film by actually performing them. There’s very little reliance on CGI, allowing, subconsciously, the viewer to recognize, somewhere in the back of our minds, that what we’re seeing onscreen is real—as opposed to the usual Hollywood confection. Cruise and McQuarrie engross the viewer by making the most outlandish stunts look and feel like they really happened.

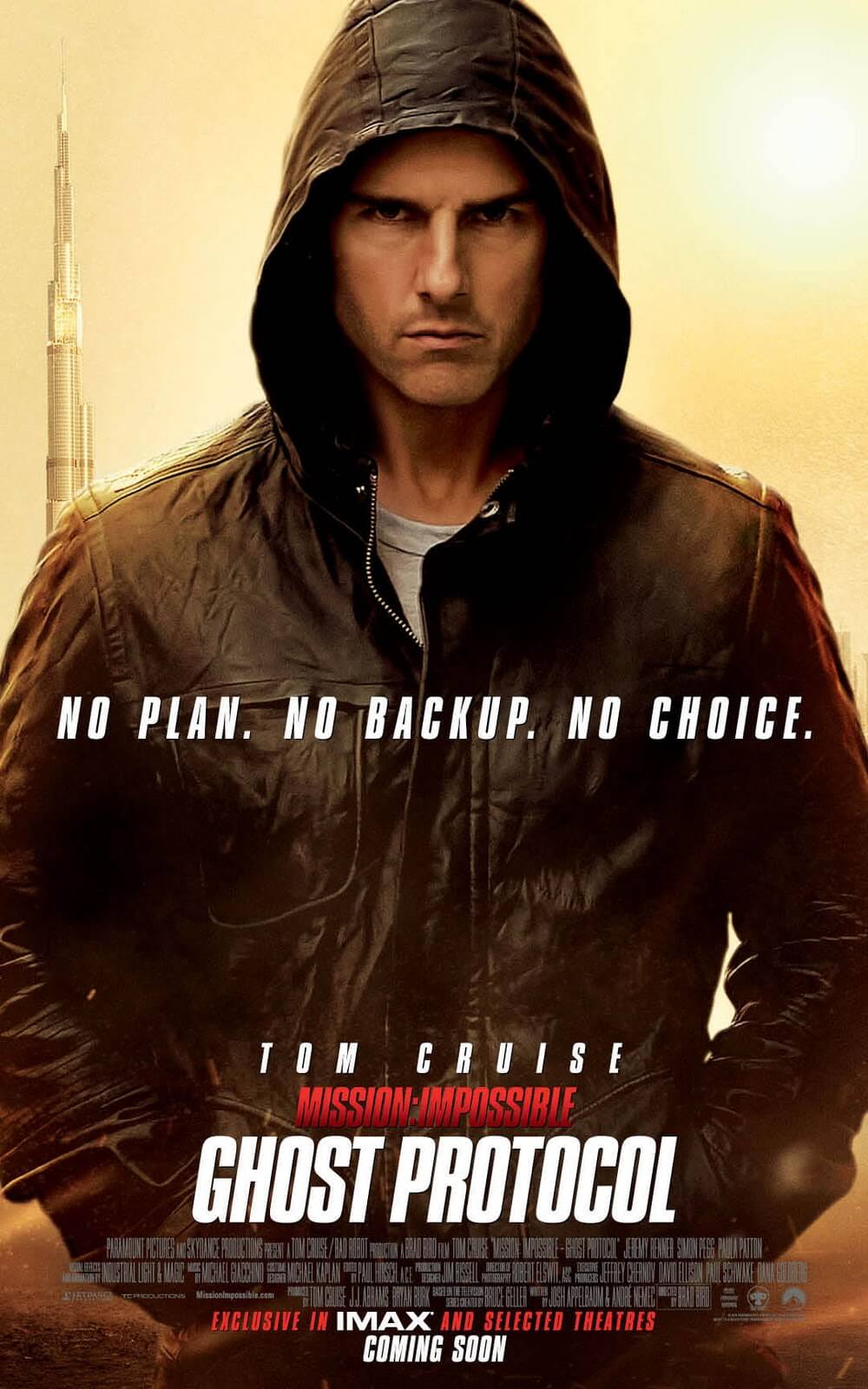

More than the first two titles in the Mission: Impossible franchise, the last few have maintained a relatively steady character base and plot after J.J. Abrams reinvigorated the material in 2006. But Fallout follows closely the events and characters from Rogue Nation, and even maintains the same villain and supporting players. IMF point man Ethan Hunt, backed by his behind-the-scenes tech support Luther (Ving Rhames) and his other techie-turned-field-man Benji (Simon Pegg), operates under the close watch of their new department head, Secretary Alan Hunley (Alec Baldwin). Hunt’s team has been tasked with taking down The Apostles, a terrorist faction devoted to the notion that “the greater the suffering, the greater the peace”—hence their resolution to cause as much suffering across the globe as possible. The Apostles follow in the footsteps of their former leader, Solomon Lane (Sean Harris), who was imprisoned by Hunt and Co. at the end of the last film. One of Lane’s devotees named John Lark, presumably a double agent in US intelligence, hopes to acquire three plutonium cores in an effort to create three nuclear weapons. Hunt’s team accepts the impossible mission to identify Lark, recover the cores, and stop Lane’s Apostles once and for all.

More than the first two titles in the Mission: Impossible franchise, the last few have maintained a relatively steady character base and plot after J.J. Abrams reinvigorated the material in 2006. But Fallout follows closely the events and characters from Rogue Nation, and even maintains the same villain and supporting players. IMF point man Ethan Hunt, backed by his behind-the-scenes tech support Luther (Ving Rhames) and his other techie-turned-field-man Benji (Simon Pegg), operates under the close watch of their new department head, Secretary Alan Hunley (Alec Baldwin). Hunt’s team has been tasked with taking down The Apostles, a terrorist faction devoted to the notion that “the greater the suffering, the greater the peace”—hence their resolution to cause as much suffering across the globe as possible. The Apostles follow in the footsteps of their former leader, Solomon Lane (Sean Harris), who was imprisoned by Hunt and Co. at the end of the last film. One of Lane’s devotees named John Lark, presumably a double agent in US intelligence, hopes to acquire three plutonium cores in an effort to create three nuclear weapons. Hunt’s team accepts the impossible mission to identify Lark, recover the cores, and stop Lane’s Apostles once and for all.

At the same time, the CIA’s Director Erica Sloan (Angela Bassett) demands one of her agents, the towering brute August Walker (Henry Cavill), oversee Hunt’s progress. She calls Walker the hammer to Hunt’s scalpel, and more than once, Walker’s unsubtle approach smashes the IMF’s carefully laid plans. Returning to the mix is Ilsa (Rebecca Ferguson), a former MI6 agent who walked away from her life of undercover spying in Lane’s Syndicate. Which is to say, it’s helpful if Fallout’s audience remembers the events in Rogue Nation, even Mission: Impossible III, to appreciate in full the emotional significance of the events here. To be sure, Hunt’s estranged wife, played by Michelle Monaghan, makes several appearances in the film, lending to Hunt’s characterization as a man driven by a terrifying fear that, should Lane and his cohorts succeed, he’ll be unable to save the people who matter most to him. For Sloan, Hunt’s willingness to sacrifice the success of an entire mission, in which millions of lives hang in the balance, in exchange for a single life, means the agent has been compromised.

The script, written by McQuarrie, rewards those who pay close attention to the plot machinations and twists throughout, without dwelling on moments or dumbing them down for an inattentive audience. About mid-film, an unassuming sequence that takes place in a series of underground tunnels contains about three twists and double-crosses in a matter of minutes, each more effective and unpredictable than the last, and McQuarrie allows them to unfold thoughtfully, trusting his audience to keep up. Not that it requires much to follow the story, as McQuarrie efficiently sketches out the stakes early in the film’s breezes-by two-and-a-half-hour runtime. The structure, modeled after the Hitchcockian ideal of grabbing the viewer from the first sequence and not letting go, never allows the viewer a moment of ease. Alfred Hitchcock has long been an influence on the franchise, from the elegantly conceived set pieces to the wrong-man-thriller elements, to the way each film forces the viewer to hold their breath until the last possible moment. Throughout the remainder, the audience follows along, either invested in the weighty dramatic arcs for characters like Hunt, Ilsa, and Benji, or attuned to the remarkable action. Most viewers will walk away from Fallout exhilarated, talking about Cruise’s stunts or the downright exhausting chases (by motorcycle, automobile, helicopter, and foot), but the story rewards those invested in the characters. And while McQuarrie’s script contains less humor or moments of levity than the previous two sequels, the lofty threat of nuclear genocide and personal loss intensifies the stakes more than previous missions.

McQuarrie began his string of collaborations with Tom Cruise as the screenwriter of Valkyrie (2008); he later directed the actor on Jack Reacher (2012) and also contributed to the deft scripting on Edge of Tomorrow (2014). Even with McQuarrie’s accomplished filmmaking on Rogue Nation, his work on Fallout is a leap in craft and skill. He’s elevated himself from a screenwriter-turned-director to an extraordinarily accomplished visualist with a fully realized aesthetic. Shot by Rob Hardy (Annihilation), there’s a soft, Nolan-esque sheen to the proceedings, recalling the look of Inception or The Dark Knight. Hardy’s rather straightforward, plainly presented lensing of the action, along with Eddie Hamilton’s editing, capture the daring and death-defying stunts in all their considerable glory. The production seems engineered to make the most of Cruise’s devotion to action realism, particularly in the last 20 minutes when Hunt inches up a payload rope attached to the bottom of a helicopter, guides himself inside to the front of the craft, and then takes over above the mountains of Kashmir, India—a stunt marked by its balance of suspense amid beautiful scenery. What’s more, Cruise performs some extraordinary motorcycle work, becomes the first actor to perform a high-altitude skydive, and runs in a wowing extended pursuit (he has long been Hollywood’s best runner). Any of these sequences is incomparable, and yet Fallout is filled with them. Then again, McQuarrie and the 56-year-old Cruise are unafraid to acknowledge that the star may be dimming. Opposite the broad-shouldered Cavill (today’s Superman), who towers over Cruise, Hunt isn’t the invincible hero he once was. In Fallout, he’s out of his depth more than once, which, of course, makes the film all the more thrilling.

McQuarrie began his string of collaborations with Tom Cruise as the screenwriter of Valkyrie (2008); he later directed the actor on Jack Reacher (2012) and also contributed to the deft scripting on Edge of Tomorrow (2014). Even with McQuarrie’s accomplished filmmaking on Rogue Nation, his work on Fallout is a leap in craft and skill. He’s elevated himself from a screenwriter-turned-director to an extraordinarily accomplished visualist with a fully realized aesthetic. Shot by Rob Hardy (Annihilation), there’s a soft, Nolan-esque sheen to the proceedings, recalling the look of Inception or The Dark Knight. Hardy’s rather straightforward, plainly presented lensing of the action, along with Eddie Hamilton’s editing, capture the daring and death-defying stunts in all their considerable glory. The production seems engineered to make the most of Cruise’s devotion to action realism, particularly in the last 20 minutes when Hunt inches up a payload rope attached to the bottom of a helicopter, guides himself inside to the front of the craft, and then takes over above the mountains of Kashmir, India—a stunt marked by its balance of suspense amid beautiful scenery. What’s more, Cruise performs some extraordinary motorcycle work, becomes the first actor to perform a high-altitude skydive, and runs in a wowing extended pursuit (he has long been Hollywood’s best runner). Any of these sequences is incomparable, and yet Fallout is filled with them. Then again, McQuarrie and the 56-year-old Cruise are unafraid to acknowledge that the star may be dimming. Opposite the broad-shouldered Cavill (today’s Superman), who towers over Cruise, Hunt isn’t the invincible hero he once was. In Fallout, he’s out of his depth more than once, which, of course, makes the film all the more thrilling.

Over the course of six films, the Mission: Impossible franchise has remained mostly consistent (with the exception of the abominable second film by director John Woo), deepening its hold on viewers with each new entry. With Fallout, McQuarrie delivers not only the best film in the franchise after De Palma’s slick original, but one of the great films of artfully photographed and technically monumental action—to be included on a list alongside other titles of similarly grand scope and design: The Road Warrior (1982), Aliens (1986), Die Hard (1988), Heat (1997), Skyfall (2012), and Mad Max: Fury Road (2015). Above all, Fallout reminds us that neither Cruise’s talent nor the enduring quality of his Mission: Impossible films should be taken for granted. Each new sequel attempts something new, something we’ve never seen before, and does this with a sense of spy-thriller panache that no other action franchise has matched with such unbridled showmanship and consistent, keeps-you-guessing story. Audiences will be watching McQuarrie’s direction and Cruise’s stuntwork for years to come, reflecting with a sense of awe over how they accomplished what they did, and how rare it is that the filmmakers took the risk to achieve it.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review