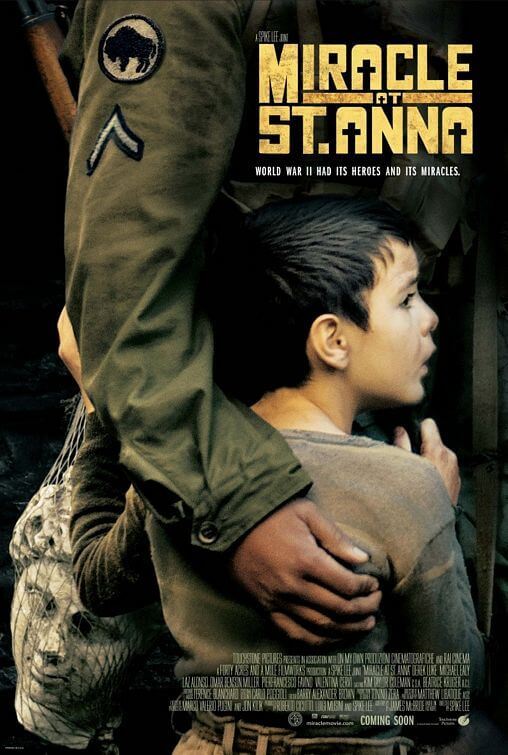

Miracle at St. Anna

By Brian Eggert |

Spike Lee’s Miracle at St. Anna displays remarkable heroism under the worst circumstances, exploring the best and worst parts of human nature in a World War II setting. Based on the 2002 novel by James McBride, the carefully researched production embraces a Saving Private Ryan-esque account and adds weighted gravitas by considering the racial and therefore humanist stakes in a narrative about African-American soldiers. But as noble as Lee’s effort might be in theory, no message, however important, can distract from the film’s desperation to be epic—a self-consciousness that results in a meandering, overstuffed, and poorly structured story.

“We fought that war, too” the elder Hector Negron utters to himself, enduring an idealized John Wayne war movie on television. Formerly of the 92nd Infantry Division of recruits, dubbed “Buffalo Soldiers”, Negron goes to work at his post office window in 1984, where he fixes onto a customer with grim recognition; from below, Negron pulls a German Luger and shoots the man in cold blood. Police later find the head of a Roman statue, missing since WWII and worth $5 million, in Negron’s apartment. This virtually anecdotal bookend begins and ends the film, though has little bearing on the two and a half hours in between.

The interesting stuff starts in 1944, behind enemy lines in a small Tuscany village. Staff Sergeant Stamps (Derek Luke), Sergeant Bishop Cummings (Michael Ealy), Corporal Hector Negron (Laz Alonso), and Private First Class Sam Train (Omar Benson Miller) are cut off from their racist commander who, not believing Stamps’ report on their location, opened up artillery on their position, creating a crossfire with German guns blasting, and killed nearly the entire squad. After the disorienting battle, Train stumbles upon a lost eight-year-old Italian boy named Angelo (Matteo Sciabordi) and befriends him, believing the boy is imbued with the ability to create miracles. With Nazi forces encroaching from all sides, Italian collaborators in their midst, and infighting among their own, miracles are just what they need.

Appreciating Lee’s indisputably talented eye behind the camera isn’t hard to do when considering the effective sequences he’s compiled: The events at the Massacre of St. Anna di Stazzema are some of the most upsetting wartime atrocities put to film, shot with equal parts sensitivity and brutality. Scenes between Train and Angelo contain touching innocence, recalling Life is Beautiful. Images of Partisan rebels in their leaf-carpeted woods are beautifully rendered. And there’s a flashback that takes our “Buffalo Soldiers” back to an Army base on American soil; entering a malt shop they find the owner refuses to serve them, meanwhile, Nazi POWs enjoy their ice cream under the eye of military police.

The hypocrisy of white racism in this scene is one of the most stirring moments in a film filled with statements on race and humanism during wartime. For volunteer soldiers signing up for Eleanor Roosevelt’s army, the least they can hope for is respect from their fellow Americans over and above the enemy; but instead, the soldiers are treated like the lowest rung on the ladder. Stamps laments that he feels “more free in a foreign land” than at home. In the Tuscany village, such sentiments are heartbreaking given the racial prejudice fuelling WWII. As an afterthought, Lee includes some notes of general humanism, stepping back from his immediate message of race-based hardships. He seems to suggest, through the universal disdain for war by individuals on each side, even the Nazi side, that war is horrible. But this is just an afterthought to his central discussion and hope for progress in racial understanding.

Despite his notes on prejudice, Lee remains an occasional sexist, again depicting his main female character as a sex object gawked at and fought over by the film’s soldiers. Valentina Cervi plays Renata, a single-minded, small-town beauty stereotype who just so happens to be the only attractive woman in Italy. Of course, someone has sex with her—what else would her character do? Most of the women in the film, at least those with dialogue, are reduced to prancing around in lingerie or taking off their shirts. This remains consistent throughout the bulk of Lee’s work, which seeks out equality, just not for women. Lee’s own chauvinism is even more apparent, and distracting, in the war movie genre where women are often shown as secondary.

Much of the film’s running time feels like dramatic fodder, neither necessary to the plot nor particularly memorable upon reflection, lending to an overall disjointed procession. Having mentioned the malt shop interlude, which I found wonderful on its own, I can’t help but think the sequence is completely unnecessary in the film’s forward motion. And then there’s an overlong section of the film’s middle spent with the Italian rebel, “The Great Butterfly” (Pierfrancesco Favino), and in view of his fate and consequence to the plot, the time feels wasted. There are several unexplored questions raised, all ruminations more than focused thoughts—a director’s signature that works for Lee on a film like Bamboozled, but here feels incoherent. Then there are the flashbacks. And flashbacks within flashbacks. At one point, a flashback narrated by “The Great Butterfly” reveals a secret he’s yet unaware of, forcing us to question how he’s able to recall such images. I suppose the interweaving subplots and storylines are collected in grand form, but they never merge into a satisfying arrangement.

Spike Lee criticized Clint Eastwood for not including African-American characters in either of his WWII films, Flags of Our Fathers or Letters from Iwo Jima. In the former case, that didn’t apply to the real-life figures, and the latter case was from the Japanese point of view. Eastwood promptly told Lee, “Shut your face.” This precursory incident to Miracle at St. Anna demonstrates Lee’s fervor over the lack of African-American representation in WWII cinema, but it also suggests that his passion has led to a desperate, occasionally sloppy attempt to assert itself in the face of other war movies. Being that his fury has driven so many of his great pictures, this marks one of the rare occasions where Lee’s anger works against his art.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review